Courtesy & Copyright Joseph Kozlowski

Used with permission

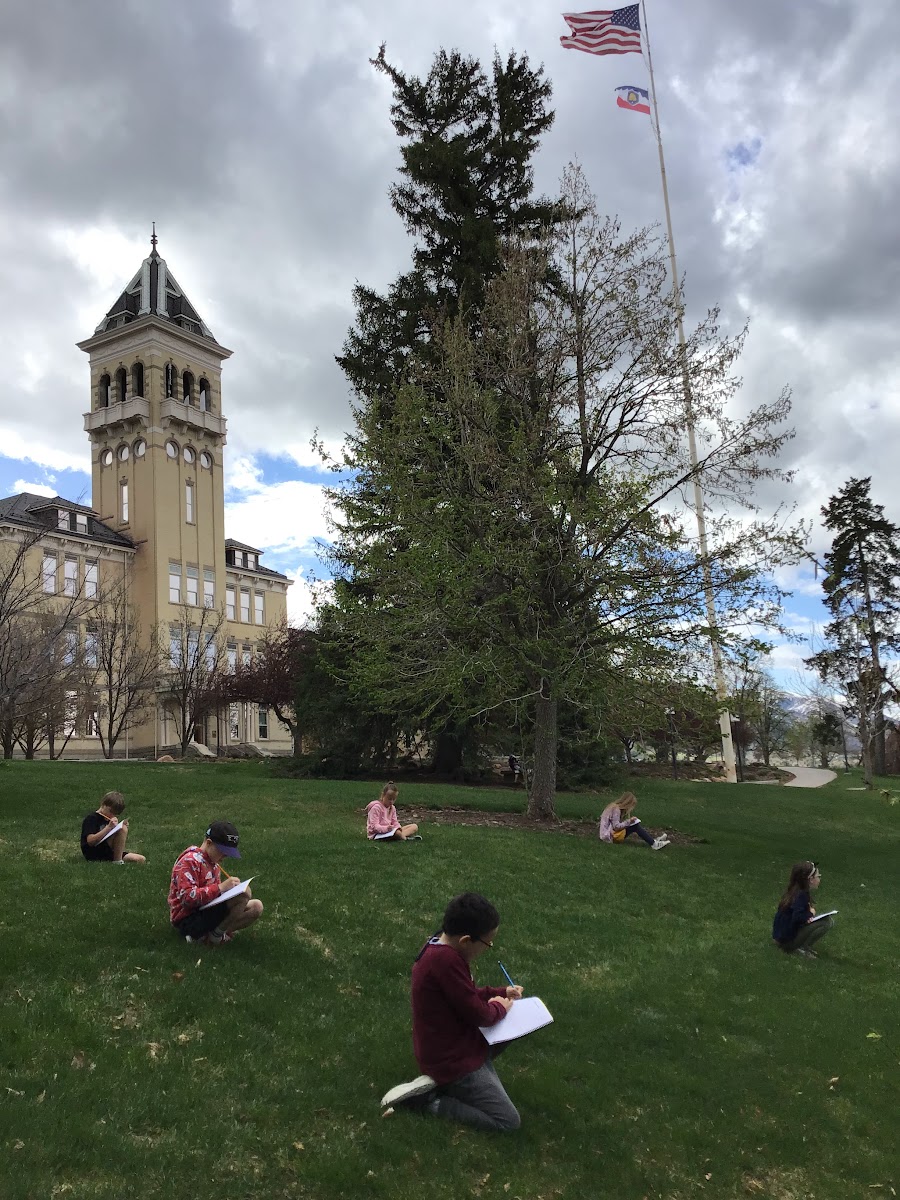

Journaling in Silence on Old Main Hill

Journaling in Silence on Old Main Hill

Courtesy & Copyright Joseph Kozlowski

Used with permission

Even a leaf can be full of wonder for a kid

Even a leaf can be full of wonder for a kid

Courtesy & Copyright Joseph Kozlowski

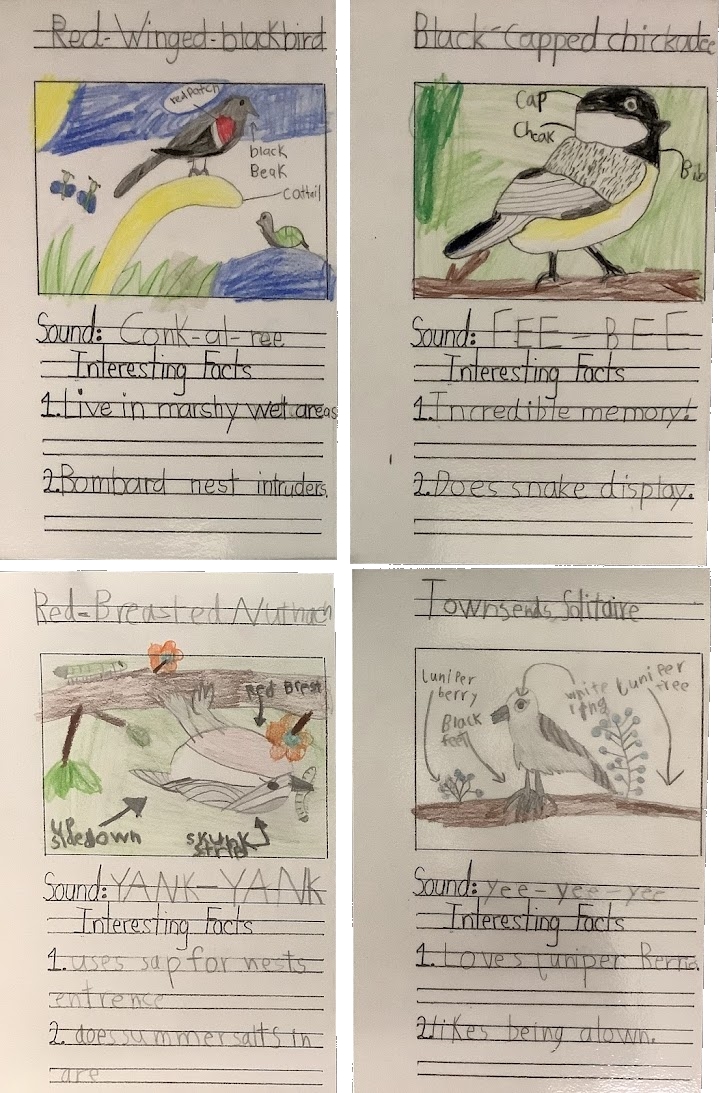

Used with permissionAt USU’s Edith Bowen Laboratory School, we call outdoor experiences with intentionality on observing and learning from the world around us, field experiences. With your family, a field experience could be anything from a simple walk around the block to a multi-night camping trip to the vast, High Uintah Wilderness area. Whether you’re a teacher trying to implement an impactful field experience with your class, or a family, looking for something meaningful to do with your kids, I’d like to share three simple techniques I’ve found help kids make meaning from the world around them when they are in the field.

One technique I’ve found useful is to dedicate time to embrace quietness. In a world where it seems like everything is moving at supersonic speed, and distractions include any number of electronic gadgets, the field can be a rare opportunity to connect with quietness and stillness once again. Although I often use field experiences to buttress relationships with my students by casually talking to them as we navigate nature, I always make it a point to devote sacrosanct time to quietness, and just allow kids to observe and think. It is amazing to see what kids notice and wonder when encouraged to enter nature’s classroom of silence. On a brisk sunny morning last spring, while sitting in stillness on USU’s Old Main Hill, a 7-year-old student of mine wrote “The leaves on the trees rustle, the birds sing to me spring songs. The leaves are good, the birds are kind. All of nature is right.’

Another technique I’ve found useful is to focus on the journey, not the end goal. I’ve found that kids, unlike myself, care little about reaching any certain destination. Instead, they seem fascinated by parts of the journey that I easily overlook such as a creek bridge formed by a fallen tree, a rubbled pile of climbable boulders, or a mucky beaver pond with hopping ribbity critters. It can be easy to feel like 45 minutes of kids scrambling around on boulders and creeping through crevices formed by the rocks is a waste of time because you’re not making progress toward your goal, but don’t be dismayed! Even if you don’t get that perfect family photo at the scenic overlook you so hoped for, the kids won’t care, they’ll just remember being professional rock climbers and scraping their palms.

Lastly, I’ve found it important to appreciate childlike wonder. You may have seen enough deer scat in your life to fill your planting boxes 10 times, but your children may be fascinated by the little brown/black nuggets. They may wonder what they are from, which may lead to discussions about moose, elk, and deer! You may find kids start to pose questions that challenge your own adult knowledge, such as how to distinguish between deer and elk poop! One recommendation here is to demonstrate adult inquiry and unknowing. Instead of whipping out your smartphone and getting an answer from the ChatGPT genius, model what it looks like to make informed hypotheses yourself, and leave the question open until later that day, when you and your child can do some follow up investigation on the questions. Oh, and by the way, I learned from a Teton Science School instructor that if you think the questionable dark brown nugget shaped scat could easily fit in your nose, go with deer poop. If it looks like it’d be a tight squeeze, you’re probably dealing with elk. And, if you’re thinking to yourself “there is no way in the world I’m getting that thing up my nostril!” you’ve likely discovered some moose droppings!

So next time you are out in the field with kids, give these few little techniques a try and see if it brings a bit more intentionality and purposefulness to your time in the majestic Utah outdoors!

This is Dr. Joseph Kozlowski, and I am wild about outdoor education in Utah!

Credits:

Images: Courtesy & Copyright Joseph Kozlowski, Photographer, Used by Permission

Featured Audio: Courtesy & Copyright © Kevin Colver, https://wildstore.wildsanctuary.com/collections/special-collections/kevin-colver

Text: Joseph Kozlowski, Edith Bowen Laboratory School, Utah State University https://edithbowen.usu.edu/

Additional Reading Links: Joseph Kozlowski & Lyle Bingham

Additional Reading:

Joseph (Joey) Kozlowski’s pieces on Wild About Utah:

Teton Science Schools, https://www.tetonscience.org/

Edith Bowen Laboratory School, https://cehs.usu.edu/edithbowen/

Rhodes, Shannon, I Notice, I Wonder, Wild About Utah, August 31, 2020, https://wildaboututah.org/i-notice-i-wonder/

Rhodes, Shannon, Wild About Nature Journaling, Wild About Utah, June 22, 2020, https://wildaboututah.org/wild-about-nature-journaling/