Himantopus mexicanus

Copyright © 2011 Holly Strand

Hi I’m Holly Strand.

On a recent Saturday my family and I visited Tracy Aviary in Salt Lake City. Walking through the wetland exhibit we saw a couple of black-necked stilts—a common Utah shorebird–snoozing near the boardwalk. They stood at the exhibit shoreline, each one balancing on a single, long, skinny, leg—the other leg drawn into the plumage underneath their bodies. Rotated almost 180 degrees, their heads and bills were tucked snugly under folded wings.

Why do birds choose to stand on just one leg? Wouldn’t it be more comfortable to distribute one’s weight on two? I’ve tried standing on one foot during yoga practice. It doesn’t feel like a good position for rest or sleep.

Over the years, several theories have emerged about this behavior in birds. One is that standing on one leg will reduce fatigue in the other leg. Then, if threatened, the bird could escape more quickly by using the rested leg to initiate motion.

Another theory is camouflage. Two parallel legs may look suspicious to ground level or aquatic prey. In contrast, one leg might resemble a reed or branch.

Perhaps the most common speculation is that birds are conserving heat via one-leggedness.

I wanted to test this last theory by standing barefoot in last weekend’s snow. First on one leg–and then on two for comparison. But I had a bad cold. I asked my biologist husband to do it for me, thinking he would be happy to support rational scientific thinking in the household. Alas, he rolled his eyes and made a noise that I’ve learned to translate as “You’ve got to be kidding me.”

Giving up on him, I dug deeper into the scientific literature.

At last I found a recent study conducted by Matthew Anderson and Sarah Williams of St. Joseph’s University. By observing Carribbean flamingoes these researchers showed that more birds stand on one foot at lower temperatures than at higher temperatures. Further, we know that loss of body heat to water is significantly greater than to air. So it would make sense to see more birds standing on one foot in the water than on land. And indeed this was the case. 80% of birds in water stood on one leg. On land, significantly less did so. Thus it does seem that temperature regulation is at least one reason for standing around on one leg.

In Utah look for one legged roosting among stilts, American avocets, night herons, double-breasted cormorants, and storks. Ducks, magpies and pigeons also stand on one foot for several minutes at a time

–it’s just harder to notice it in them because of their short legs.

For Wild About Utah, I’m Holly Strand.

Credits:

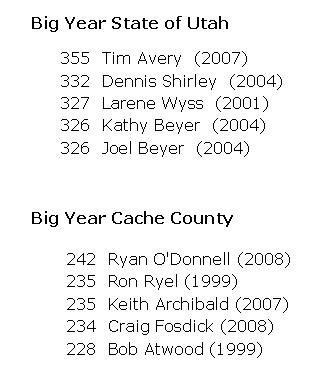

Table: Courtesy & Copyright © 2011 Holly Strand

Text: Holly Strand

Sources & Additional Reading:

Anderson, Mathew and Sarah A. Williams. 2010. Why do flamingos stand on one leg? Zoo Biology. Volume 29, Issue 3, pages 365–374, May/June 2010

Clark Jr., GA. 1973. Unipedal postures in birds. Bird-Banding, 44:22–26.

Tracy Aviary in Salt Lake City https://www.tracyaviary.org/