Courtesy & Copyright Hilary Shughart, Photographer

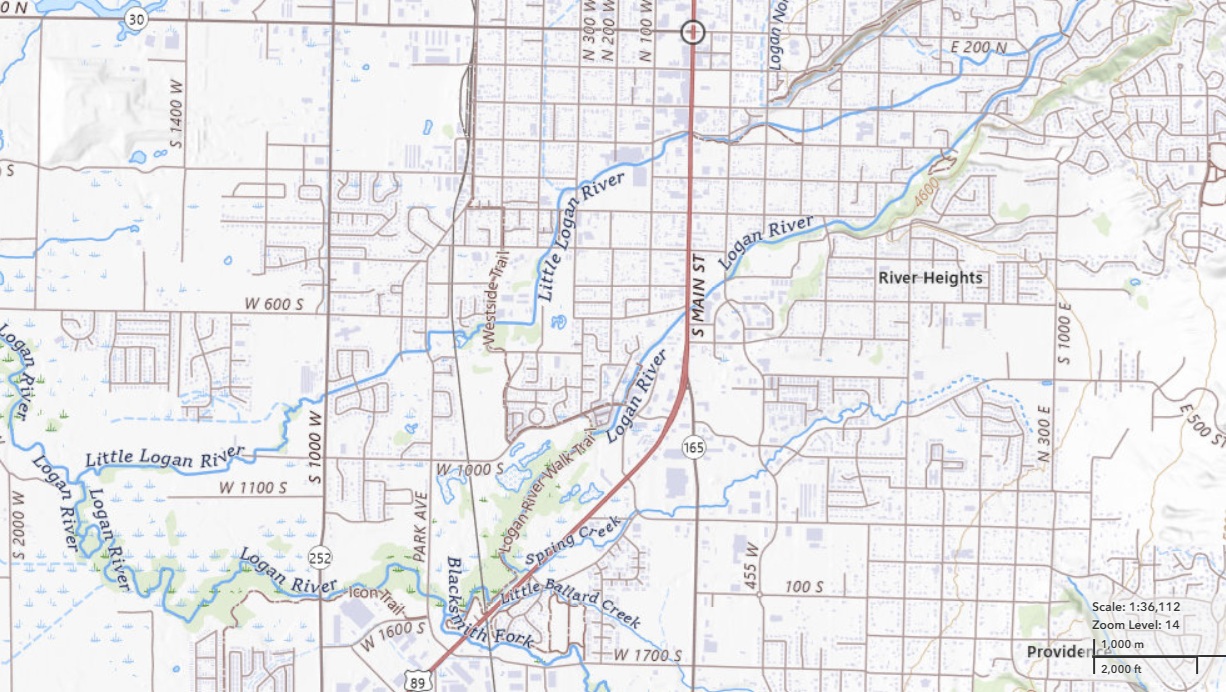

Click for a larger view in a new tab or window and search for or zoom-in to Logan UT, https://apps.nationalmap.gov/viewer/

Let’s celebrate our Logan Island Twin Rivers Reverence Vibe with poetry and conservation actions, such as planting native plant riparian buffers and ensuring this Tree City USA maintains a healthy tree canopy, clean water, and a thriving Natural Stream Environment, filled with the delights of birds and bird song, which are actual metrics of the health of a city.

The Logan Island Twin Rivers Reverence Vibe

The Logan River meanders gracefully from the mouth Logan Canyon,

Generating electricity here, filling First Dam Reservoir there,

Flowing through the World Class Utah State University Water Research Laboratory,

With a mile and a half southwesterly meander past Herm’s Inn here, and River Hollow Park there,

Forking to wrap around the Logan Island, twin blue trails

weaving green stripes of riverside parks,

Sustaining our urban ecosystem,

This one wild and beautiful Logan Island

Twin Rivers Reverence Vibe,

Natural Community,

Lifeline.

I’m Hilary Shughart with the Bridgerland Audubon Society, and I am Wild About the North and South Branches of the Logan River, and I am Wild About Utah!

Credits:

Images: Little Logan River Courtesy & Copyright Hilary Shughart, Photographer

Featured Audio: Courtesy Friend Weller, Chief Engineer Retired, UPR.org, Courtesy & Copyright © Kevin Colver, https://wildstore.wildsanctuary.com/collections/special-collections/kevin-colver

Text: Hilary Shughart, President, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading: Hilary Shughart and Lyle Bingham, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading

Other Wild About Utah pieces authored by Hilary Shughart

Save and Restore the North Branch of the Logan River (Little Logan River), Bridgerland Audubon Society, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/llr/

| Guide to The Logan River Trail iFIT parking lot to Trapper Park Read to Logan City Council April 1, 2025 by Logan Poet Shanan Balkan, First, we pass under the traffic bridge Bright green watercress thrives See the majestic Wellsville mountains Turn around and see the Bear River Mountains Now we pass the pastures that fence horses— Hear the music of frogs croaking, The air vibrates with the jubilant At the bend in the trail, we hear Here comes the man with one hiking pole Past the pond, there is the black metal bench In summer, there are clouds Onto the second bridge, We pass the mobile home park And then onto the cow pastures Look! A bald eagle! And then to the sidewalk but before we get there, Guide to The Logan River Trail

iFIT parking lot to Trapper Park Read to Logan City Council, April 1, 2025 by Logan Poet Shanan Balkan https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/… |

Save and Restore the North Branch of the Logan River (Little Logan River), Bridgerland Audubon Society, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/llr/