Trimerotropis modesta

Courtesy & © 2010 https://bugguide.net/node/view/466693

David Bygott, Photographer

Utah has neither snapping turtles nor snapping shrimp, but we do have snapping grasshoppers. Their loud crackling sound punctuates summer hikes along open canyon slopes and rocky mountain ridges. (recording of a snapping grasshopper) Like other band-winged grasshoppers, they are named for the arcs of muted color across their hind wings.

But it is the male’s insistent racket that draws our attention. A snap results when a stout vein of their hind wings is flexed between two positions. That flexure alternately stretches and relaxes the membrane between the veins, something like an umbrella being popped open and then folded. The vein flexure generates an audible snap, like a dog’s training clicker. (recording of dog clicker) The grasshopper’s loopy flight generates a train of snaps. (recording of snapping grasshopper)

Crepitating cicadas have a similar means of sound production. They click from a perch on a plant stem. (recording of cicada) Their clicking has filled the air of northern Utah this summer.

As with cicadas, it is the male band-winged grasshopper that snaps to woo a mate. He displays solitarily during flight, the longer advertisement the better, apparently. Hopefully, an attracted female will meet him in the air. Sadly for the male, most of the time no female responds and he lands unrequited. There the previously conspicuous male seems to silently vanish, so perfectly does his mottled tan camouflage match bare ground. After resting a bit, he launches again to resume his crackling display.

Species of band-winged grasshopper differ in their snapping displays, which a female no doubt appreciates. But for you and I, it is enough to know that we are hearing snapping grasshoppers on a warm day’s hike.

Credits:

Images: Courtesy © 2010 David Bygott, Photographer, bugguide.net

Audio: Jim Cane, Bridgerland Audubon Society

Text: Jim Cane, Bridgerland Audubon Society

Additional Reading:

Otte, Daniel. 1970. A Comparative Study of Communicative Behavior in Grasshoppers.

Miscellaneous Publications Museum of Zoology, University Of Michigan, No. 141 https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/56385/MP141.pdf?sequence=1

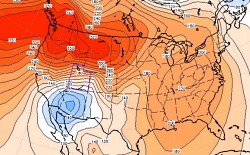

Air Pressure at the Surface, 1 Dec 2011

Air Pressure at the Surface, 1 Dec 2011