Cover Courtesy Alaska Stock Images, © Johnny Johnson, R. E. Johnson Photographers

Maps illustrated by David Lindroth

Photo Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell

Photo Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell

Logan Canyon Tree

Logan Canyon Tree

Photo Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell

Logan Canyon Forest

Logan Canyon Forest

Photo Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell

Logan Canyon

Logan Canyon

Photo Courtesy & Copyright Eric NewellThe snow came late this year. If it is a measuring stick, Beaver Mountain ski area, in Logan Canyon, did not open before Christmas for the first time since 1977. The lifts started turning the last day of 2025.

Every tree, every elk and deer, every squirrel, every insect, every living thing in the Bear River Mountains prepared for winter weeks, even months, ago. The whole range seemed to sit in eerie limbo, waiting for the snow to fly.

This past week, I found myself pondering the immense weight of the world in the midst of the first real winter storm of the season—at least for me. I looked up from my feet at millions of snowflakes descending upon me, crisscrossing one another in a flurry. I’m talking about giant conglomerate snowflakes. The kind that transform the sky into a straight-up dreamland. I felt pure delight.

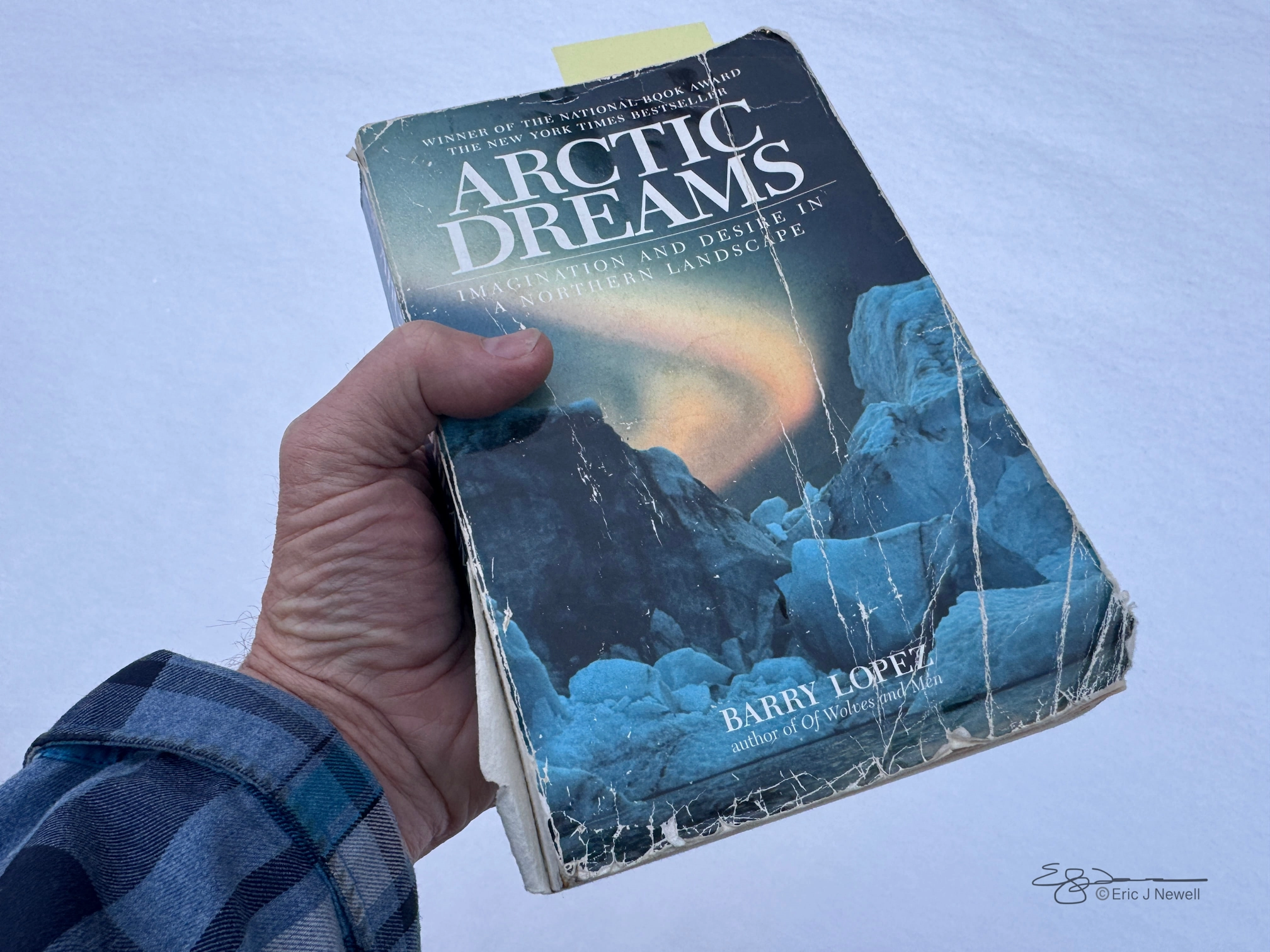

The other day, I pulled Barry Lopez’s 1986 New York Times best seller, Arctic Dreams, from my bookshelf and browsed the passages I had highlighted or underlined 25 years ago. Until his death in 2020, Lopez wrote his books on an IBM Selectric III typewriter.

Lopez asked the questions, “How do people imagine the landscapes they find themselves in?” and “How does the land shape the imaginations of the people who dwell in it?”

I imagined each snowflake as gift from the Pacific. Tiny droplets of frozen water meandering to the ground. Each is part of an endless cycle of water, dating back to the origins of the earth. I wondered how long ago these snowflakes last fell free through the sky. How long did they spend in the depths of the ocean? Where will they go on their journey from here? And how did I happen to be in this place, with these snowflakes, in this moment in time?

Everything is temporary—a snowflake, a lifetime, human history, even geologic time.

In another passage Lopez wrote: “Because [humans] can circumvent evolutionary law, it is incumbent upon [us], say evolutionary biologists, to develop another law to abide by if [we] wish to survive…. [We] must learn restraint. [We] must derive some other, wiser way of behaving toward the land.”

To that I would add, we must also derive some other, wiser way of behaving towards one another because the greatest threat to humanity is, frankly, humanity. The biggest threat to life on earth isn’t the sun’s eventual demise or a rouge asteroid. It is us. Can we learn to live sustainably, and can we learn to understand and respect those who are different from ourselves?

Later, Lopez continues the thought:

“The cold view to take of our future is that we are therefore headed for extinction in a universe of impersonal chemical, physical, and biological laws. A more productive, certainly more engaging view, is we have the intelligence to grasp what is happening, the composure not to be intimidated by its complexity, and the courage to take steps that may bare no fruit in our lifetimes.”

That requires collective action.

As Oscar Schindler identified in Schindler’s List, power is when we have every justification to take, or to control, or to act on impulse, and we don’t. We refrain.

Each snowflake individually seems insignificant, but together, relentless by the millions, snow crystals pile up. They cover the ground, flock the trees, and settle into the gaps of my jacket. Their strength is in their numbers and their ability to bond with each other.

I imagine snow accumulating on a steep mountain. As the storm rages, the sheer weight of snow increases, one single snowflake at the time, until finally, one seemingly insignificant snowflake settles on the surface, and it is suddenly too much for buried weak layers to withstand. Then, “Whoomph!” The result is a spontaneous avalanche. Inertia is both a property of matter and a property of culture.

In the big scheme of geologic time and human history, each of us are insignificant. Yet the power of our collective consciousness and action is significant. We have the capacity to lesson our footprint on the earth and deepen our impact on one another through small gestures that accumulate like falling snow: To consume less, to care more, to increase our capacity to love and understand, to be both frugal and generous, to be curious rather than judgmental, to smile or laugh with a stranger or a friend.

I catch several snowflakes on my tongue, as I walk through the blizzard, trying to pick out the biggest ones—the ones that are barely able to cling together. Several snowflakes crash-land on my face. I blink them off my eyelashes. One flake that I miss, spirals as it falls faster than the others. Each snowflake feels like a blessing from above that represents some kind of hope. Hope that the rivers will swell to fill their banks in April and May; hope that high mountain springs will gush throughout summer, hope for renewal that comes with each spring, and yes, hope for humanity.

I am Eric Newell, and I am wild about Utah snow and the power of small gestures.

Credits:

Images: Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell, Photographer

Featured Audio: Courtesy & Copyright © J. Chase and K.W. Baldwin

Text: Eric Newell, Edith Bowen Laboratory School, Utah State University

Additional Reading: Eric Newell

Additional Reading

Wild About Utah Pieces by Eric Newell

Links:

Caswell, Kurt, His Life Helped: In Memory of Barry Lopez, 1945-2020, Terrain.org, Terrain Publishing, January 11, 2021, https://www.terrain.org/2021/currents/his-life-helped/

Barry Lopez died on December 25th

The proselytiser for a different understanding of landscape and Nature was 75, The Economist Newspaper Limited, https://www.economist.com/obituary/2021/01/02/barry-lopez-died-on-december-25th

O’Connell, Nicholas, At One With The Natural World Barry Lopez’s adventure with the word & the wild, March 24, 2000, Commonweal Magazine, https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/one-natural-world-0

Beaver Mountain [Ski Resort], https://www.skithebeav.com/

Logan Avalanche Forecast Page, Utah Avalanche Center, https://utahavalanchecenter.org/forecast/logan