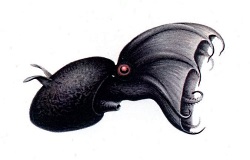

Photo Courtesy US FWS

Brett Billings Photographer

Hi, I’m Holly Strand.

Every fall, I cringe when I hear the soft thumps caused by feathery bodies slamming into the windows of our house. Etched designs into the window glass do not seem to deter these miniature kamikaze pilots.

The most intense period of window strikes occurs when birds are feasting on our chokecherries and crabapples. The birds get intoxicated from the naturally fermented fruit and their judgement flies out the window—or rather, into the window. Robins, waxwings and other fruit eaters are the most frequent flyers under the influence.

Ornithologists estimate that in the United States alone well over 100 million birds are killed each year by window collisions. Many accidents occur when birds see trees, sky, or clouds reflected on a glass but do not see the hard transparent window surface itself. Sometimes the birds are merely stunned and recover in a few moments. Often, however, window hits lead to severe internal injuries and death.

Ornithologist Pete Dunne found that feeders placed 13 feet away from a window corresponded with maximum deaths. However, a feeder place within a meter of window actually reduced the accident rate. Birds focus on the feeder as they fly toward the window. If they strike the glass leaving the feeder, they do so at very low speed.

You can redirect the accident prone birds by putting up awnings, beads, bamboo, or fabric strips. Stickers or silhouettes will help if they are spaced 2-4 in. apart across the entire window. At our house, taping some reflective ribbon to the window so that it flutters in the breeze has been very effective.

If you find a bird dazed from a window hit, place it in a dark container with a lid such as a shoebox, and leave it somewhere warm and quiet, out of reach of pets and other predators. If the weather is extremely cold, you may need to take it inside. Do not try to give it food and water, and resist handling it as much as possible. The darkness will calm the bird while it revives, which should occur within a few minutes, unless it is seriously injured. Release it outside as soon as it appears awake and alert.

For Wild About Utah, I’m Holly Strand.

Credits:

Photo Courtesy US FWS, Brett Billings Photographer, https://www.fws.gov/digitalmedia/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/natdiglib&CISOPTR=9516

Text: Holly Strand

Sources & Additional Reading:

Dunne, Pete. 2003. Pete Dunne on Bird Watching: The How-to, Where-to, and When-to of Birding. HMCo Field Guides. https://www.amazon.com/Pete-Dunne-Watching-Where-When/dp/0395906865

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Bird Notes from Sapsucker Woods. https://www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/notes/BirdNote10_Windows.pdf (Accessed Nov 30, 2008)

Leahy, Christopher. 1982. The Birdwatcher’s Companion. NY: Grammercy Books. https://www.amazon.com/Birdwatchers-Companion-North-American-Birdlife/dp/0691113882/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1228882143&sr=1-1

Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Northern Utah, Ogden, UT https://www.wrcnu.org/