Fishlake National Forest, Utah

Courtesy & Copyright 2010 Ron Ryel

Utah State University

Hi, I’m Holly Strand from Stokes Nature Center in beautiful Logan Canyon.

What we consider to be the world’s largest organism has changed over time. At one point, the largest animal crown went to a 150 ton female blue whale. And General Sherman, a 275 foot tall Giant Sequoia was the largest plant.

In 1992, scientists discovered a fungus in northern Michigan and proclaimed it to be the world’s largest organism. Not nearly as visually stunning as a Giant Sequoia, this type of fungus is a filagree of mushrooms and rootlike tentacles spawned by a single fertilized spore. Over time it had grown to cover 37 acres, most of this below ground. Subsequent mushroom hunts uncovered even larger specimens elsewhere.

Stretching over 1,600 miles and visible from space, I often hear the Great Barrier Reef called the world’s largest organism. But the reef is not a single organism. It is created from the limestone secretions of a great number of different reef-producing coral species.

Fungi, reefs and giant trees are all very worthy biological wonders, but the thing that gets my largest organism vote is right here in Utah. Like the Great Barrier Reef, it’s so vast you really need to see it from a plane or even satellite. Like General Sherman, it has its own name—Pando—-meaning “I spread” in Latin. Pando can be seen is spreading itself in Fishlake National Forest in south central Utah. So what is Pando? And why is it so remarkable?

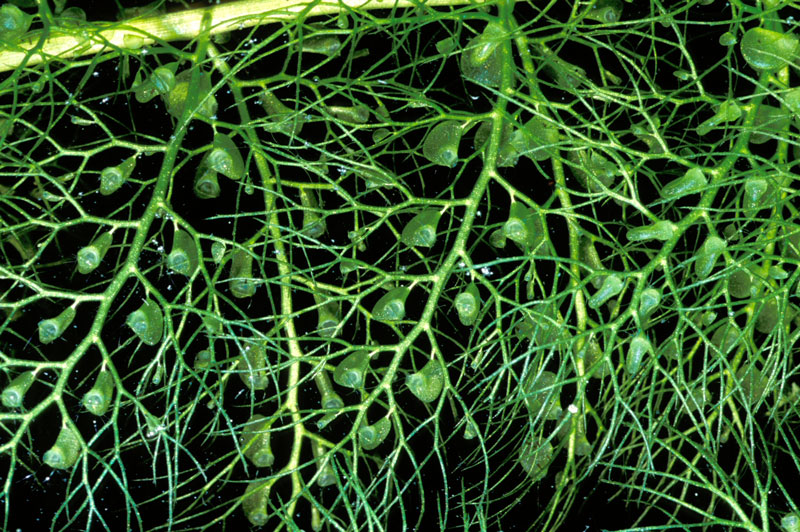

Pando is a clonal aspen colony. Each “tree” that we see in an aspen forest is not an individual tree at all but a genetically identical stem connected underground to its parent clone. More trees arise from lateral roots, creating a group of genetically identical trees. But, biologically speaking, the colony is just one individual plant.

Recent genetic testing by Dr. Karen Mock of Utah State University confirms Pando’s enormous size- it covers over 106 acres and contains around 47,000 aboveground stems or suckers. When you consider the volume represented by the trees and root system, Pando easily wins the title of world’s largest organism. So far anyway.

Thanks to Dr. Karen Mock of Utah State University’s College of Natural Resources for her help in developing this piece.

For pictures and sources of the remarkable Pando, see www.wildaboututah.org

For Wild About Utah and Stokes Nature Center, I’m Holly Strand.

Credits:

Photo: Courtesy & Copyright 2010 Ron Ryel, Utah State University

Text: Stokes Nature Center: Holly Strand

Sources & Additional Reading

WESTERN ASPEN ALLIANCE is a joint venture between Utah State University’s College of Natural Resources and the USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station, whose purpose is to facilitate and coordinate research issues related to quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) communities of the west. https://www.western-aspen-alliance.org/

American Cetatcean Society. Fact Sheet on the Blue Whale. https://www.acsonline.org [Accessed September 2, 2010]

DeWoody J, Rowe C, Hipkins VD, Mock KE (2008) Pando lives: molecular genetic evidence of a giant aspen clone in central Utah. Western North American Naturalist 68(4), pp. 493–497. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/aspen_bib/3164

Grant, M., J.B. Mitton, AND Y.B. Linhart. 1992. Even larger organisms. Nature 360:216. https://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v360/n6401/abs/360216a0.html AND https://doi.org/10.1038/360216a0

Grant, M. 1993. The trembling giant. Discover 14:83–88. Abstract:https://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.3398/1527-0904-68.4.493

Habeck, R. J. 1992. Sequoiadendron giganteum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [Accessed September 2, 2010].

Mock, K.E., C . A. Rowe, M. B. Hooten, J. DeWoody and V. D. Hipkins. Clonal dynamics in western North American aspen (Populus tremuloides) Molecular Ecology (2008) 17, 4827–4844 https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/wild_facpub/163/

Volk, T. J. 2002. The Humongous Fungus–Ten Years Later. Inoculum 53(2): 4-8. https://msafungi.org/wp-content/uploads/Inoculum/53(2).pdf

The Associated Press, Study finds huge aspen grove continues to decline, The Salt Lake Tribune, Oct 22, 2018,

https://www.sltrib.com/news/2018/10/22/study-finds-huge-aspen/

Davis, Nicola, Sound artist eavesdrops on what is thought to be world’s heaviest organism, The Guardian, May 10, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/may/10/sound-artist-eavesdrops-on-what-is-thought-to-be-worlds-heaviest-organism-pando-utah

The Sweet Song Of The Largest Tree On Earth, Science Friday, National Public Radio, May 12, 2023, https://www.sciencefriday.com/segments/listen-to-the-pando-largest-tree/