Courtesy & Copyright Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Faith Jolley, Photographer

Quagga Mussels Exposed at Lake Powell

Quagga Mussels Exposed at Lake Powell

Courtesy & Copyright Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Phil Tuttle, Photographer

Quagga Mussels Exposed at Lake Powell

Quagga Mussels Exposed at Lake Powell

Courtesy & Copyright Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Phil Tuttle, Photographer

Watercraft Inspection Point

Watercraft Inspection Point

It is unlawful to drive past an open inspection station when carrying watercraft

Courtesy & Copyright Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Faith Jolley, Photographer

Technician Pressure Washing Watercraft with 140 F Water

Technician Pressure Washing Watercraft with 140 F Water

Courtesy & Copyright Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Faith Jolley, Photographer

Entering Decontamination Dip Tank

Entering Decontamination Dip Tank

Courtesy & Copyright Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Michael Christensen, PhotographerNature lovers need to be concerned about invasive aquatic species, especially the devastating potential of quagga mussels and their close relatives zebra mussels. Although these invertebrates don’t move much as adults, it is important to understand how they traveled here, the reasons these mussels are dangerous, and the ways their proliferation can be prevented.

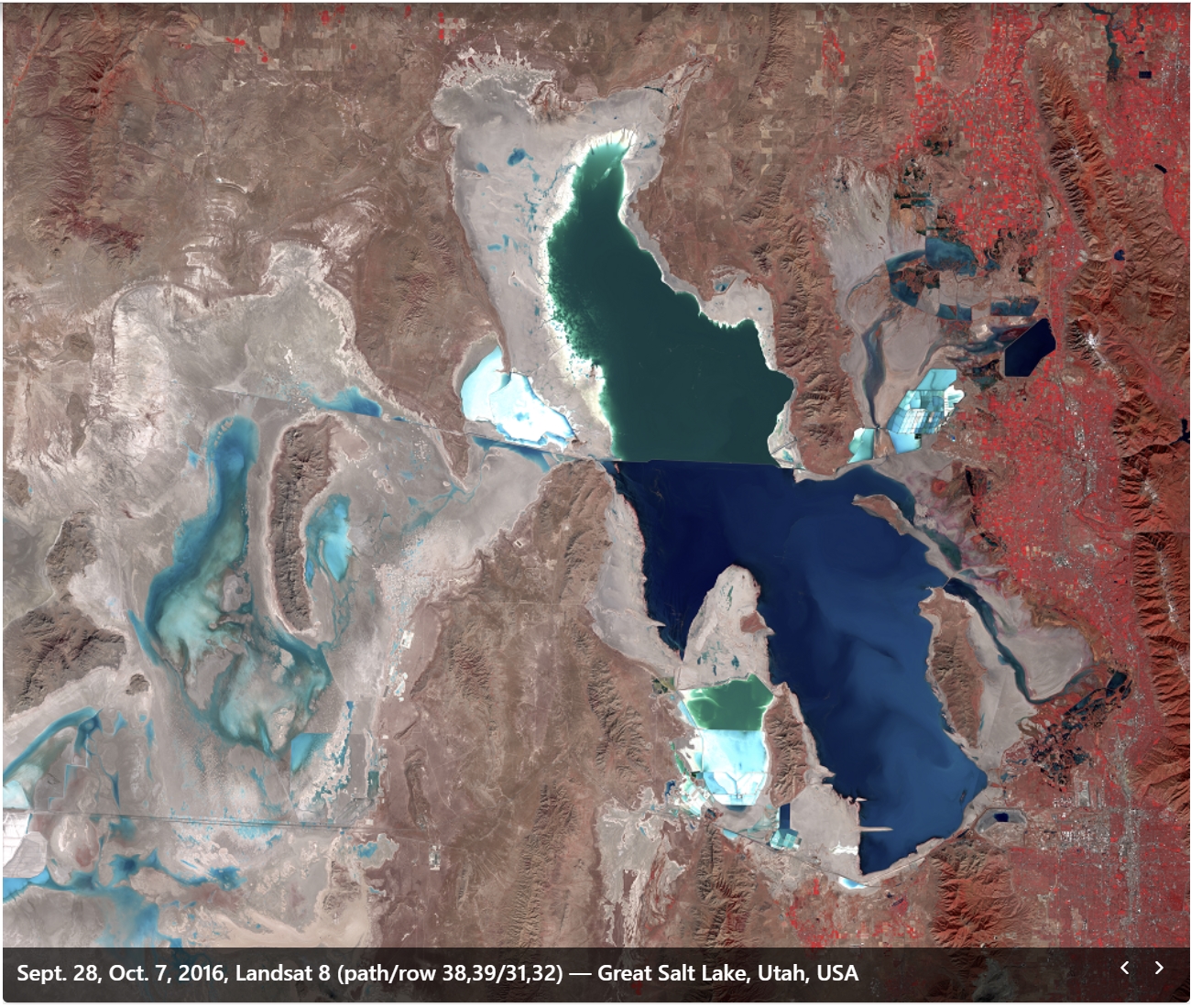

Dan Egan in his Death and LIfe of the Great Lakes explains that quagga mussels and zebra mussels migrated from the waters of the Black and Caspian seas to the Great Lakes in the ballast tanks of ocean-going freighters. Since 1989, these mussels have hitch-hiked on boats across the Great Lakes and throughout the Mississippi River drainage. They traveled up the Missouri into Montana and across the continental divide to Lake Mead, down the Colorado to California, and upstream to Lake Powell. Currently, they cover much of the United States except for parts of Utah and the Northwest.

The threat from quickly spreading, voracious, mussels is real. Quaggas reproduce better than most freshwater mussels, each spawning as many as one million microscopic veligers per year. Since mussels filter plankton from freshwater so well, little is left to nourish fish and aquatic insects. Mussels also grow quickly where water moves: piling on top of each other, clogging pipes, and fouling propellers. Unfortunately, the damage is not limited to watercraft. Water delivery pipes and power generation structures also suffer. Even death doesn’t get rid of them. Shells make beaches dangerous for bare hands and feet. Where quagga mussels take hold, the mitigation costs to private citizens and municipalities multiply dramatically.

Utah is using education, licensing, and assistance to keep invasives from spreading to other waters. Everyone operating motorized watercraft of any kind in Utah is required to take and pass the informative, mussel-aware boater course every year; pay an invasive species fee; affix stickers to watercraft; and display documents in each launch vehicle. The education effort emphasizes why watercraft surfaces, piping, and enclosed spaces must be thoroughly cleaned to prevent new infections. Although not licensed, rafts, float tubes, waders, and fishing equipment also require attention.

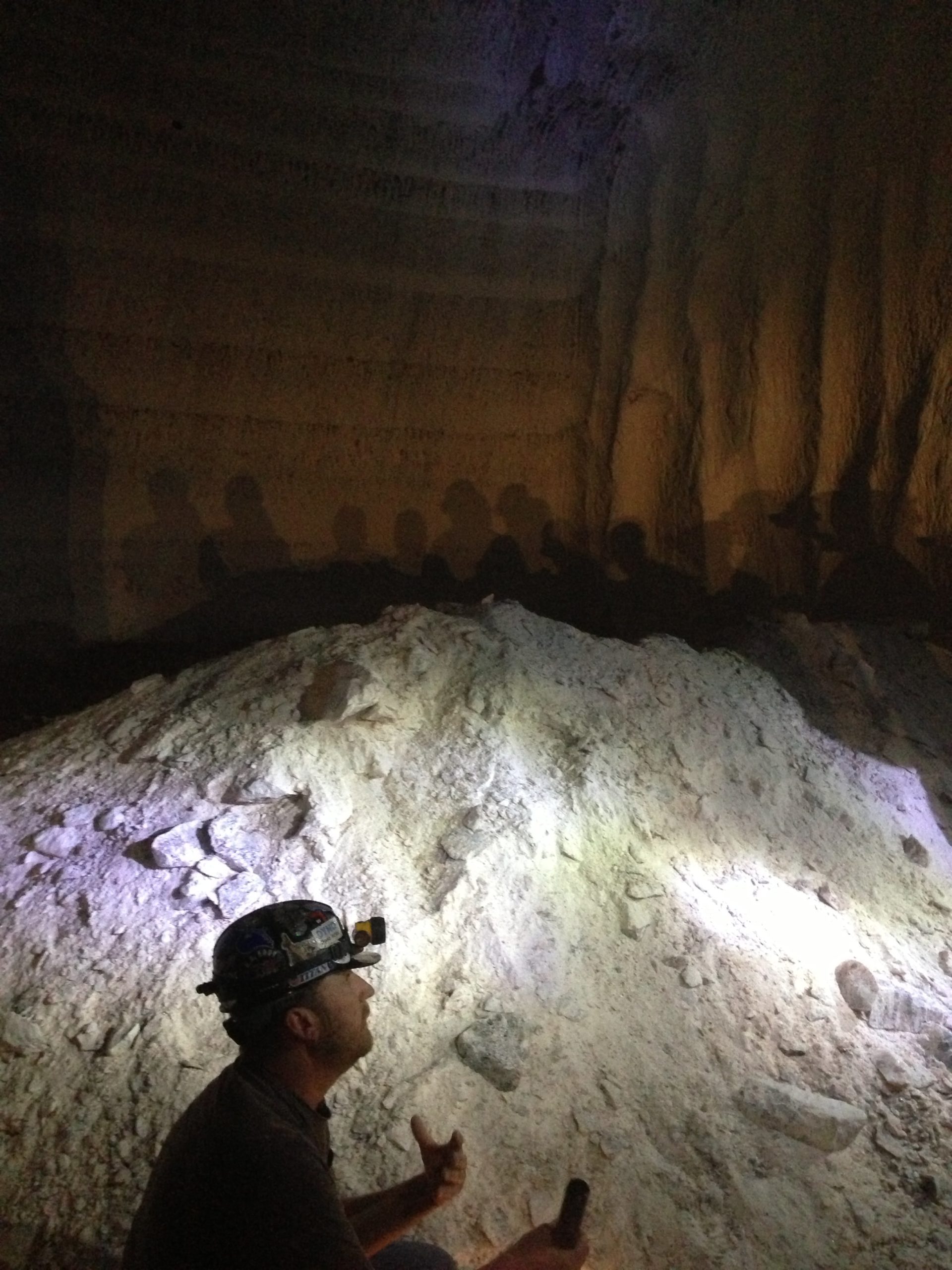

Stopping proliferation is the emphasis of the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. Aquatic Invasive Species Lieutenant, Bruce Johnson, reminds everyone to “Clean, Drain, and Dry” all watercraft. Then he explains how the DWR can assist owners navigating the mandatory statewide inspection and cleanout stations. There, wildlife technicians inspect all watercraft and have the option to pressure wash visible and hidden recesses with 140-degree water. Alternatively, they can apply a seal, sequestering watercraft from relaunch until after a mandated 7-30 day drying period passes. But pressure washing a boat and trailer takes about 45 minutes and drying takes weeks. So recently, to improve treatment quality, enhance safety, and speed up the process, the DWR installed decontamination dip tanks. Dip tanks take about 10 minutes, and are much faster than a lengthy power wash. As officials add more dip tanks across the state, only the invasive species come up short.

The threat posed by invasive mussels requires everyone’s attention. Cleaning watercraft is the beachhead. Making sure mussels don’t get carried to new waters is the quest.

I’m Lyle Bingham for Bridgerland Audubon and I’m Wild About Utah and controlling invasive species.

Credits:

Photos: Courtesy & Copyright Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Faith Jolley, PIO

Featured Audio: Courtesy & Copyright © Friend Weller, Utah Public Radio upr.org

Text: Lyle Bingham, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading: Lyle Bingham, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading

Lyle Bingham’s Wild About Utah Postings

Hellstern, Ron, Invasive Species, Wild About Utah, September 24, 2018, https://wildaboututah.org/ron-describes-exotic-invasive-species/

Egan, Dan, The Death and Life of the Great Lakes, W. W. Norton & Company, 2017, https://www.amazon.com/Death-Life-Great-Lakes/dp/0393246434

Egan, Dan, How invasive species changed the Great Lakes forever. Zebra mussels, quagga mussels have turned the lakes’ ecosystem upside down, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, September 2, 2021, https://www.jsonline.com/in-depth/archives/2021/09/02/how-zebra-mussels-and-quagga-mussels-changed-great-lakes-forever/7832198002/

Dan Egan, Leaping out of the lakes: Invasive mussels spread across America. Officials at Lake Powell fought for a decade to keep out quagga mussels. They lost the fight., Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, September 2, 2021, https://www.jsonline.com/in-depth/archives/2021/09/02/leaping-out-lakes-invasive-mussels-spread-across-america/5562151001/

Mull, Ann, Spears, Lori, Quagga Mussel (Dreissena bugensis) and Zebra Mussel (Dreissena polymorpha), Extension, Utah State University, https://extension.usu.edu/pests/research/quagga-mussel-and-zebra-mussel

Mull, Ann, Spears, Lori, Quagga Mussel (Dreissena bugensis) and Zebra Mussel (Dreissena polymorpha), Utah Pests, USU Extension, June 2021, https://extension.usu.edu/pests/research/quagga-mussel-and-zebra-mussel

Mull, Ann, Spears, Lori, Quagga Mussel and Zebra Mussel, Dreissena polymorpha Pallas and Dreissena bugensis Andrusov, Fact Sheet, USU Extension, https://extension.usu.edu/pests/factsheets/quagga-mussel-and-zebra-mussel1.pdf

Benson, Amy, Chronological history of zebra and quagga mussels (Dreissenidae) in North America, 1988-2010, USGS Ecosystems Mission Area, https://www.usgs.gov/publications/chronological-history-zebra-and-quagga-mussels-dreissenidae-north-america-1988-2010

Quagga Articles on USGS.gov https://www.usgs.gov/search?keywords=quagga

Quagga mussel – Water Education Foundation https://www.watereducation.org/aquapedia-background/quagga-mussel

Zebra mussels: What they are, what they eat, and how they spread, Lilly Center for Lakes & Streams, Grace College, October 7, 2020, https://lakes.grace.edu/what-are-zebra-mussels/

Invasive mussels Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, August 14, 2023, https://wildlife.utah.gov/fishing/invasive-mussels.html

Quagga Mussels (AIS) | Utah State Parks https://stateparks.utah.gov/activities/boating/quagga-mussels-ais/

What are Aquatic Invasive Species, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, https://stdofthesea.utah.gov/ais/what-are-they/

New boat decontamination dip tank installed at Utah Lake; other locations announced, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, June 29, 2023, https://wildlife.utah.gov/news/utah-wildlife-news/1699-new-boat-decontamination-dip-tank-installed-at-utah-lake.html

Other Ways to Prevent Invasive Species:

Don’t ditch a fish!, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, https://wildlife.utah.gov/dont-ditch.html

Don’t Let it Loose, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, https://www.dontletitloose.com/rehoming-a-pet/utah/