Courtesy Wikimedia, This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

I got off my bike and ventured partway down the driveway. Suddenly I found myself face to face with a fully grown peacock. This distant relative of Cache Valley’s native birds seemed quite at home in the shady backyard. As I glanced around, I realized it was his home. From where I was standing I could see at least ten more peacocks and peahens.

Courtesy Pixabay, Anrita1705, Contributor

Peahen on Tractor Cab

Peahen on Tractor Cab

Courtesy & Copyright Mary Heers, Photographer

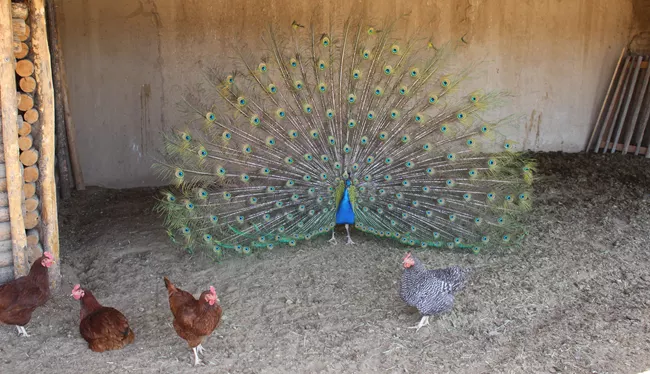

Peacock and Chickens

Peacock and Chickens

Courtesy US NPS, Bent’s Fort National Monument, New Mexico

Peahen

Peahen

Courtesy & Copyright Mary Heers, PhotographerThen I noticed the farmer sitting in his truck at the end of the driveway. He beckoned me over and gave me the whole story.

Many years ago, he had gone to Idaho and purchased a peacock and a peahen. The peahen ran off, so he went back and got another pair. This time it worked. The pair produced a nest full of eggs which the peahen diligently sat on for four weeks. She then tended the baby chicks for the week it took them to learn to fly up into the relative safety of the trees in the yard. The small family made itself at home, settling into a routine of spending their days on the ground and their nights in the trees.

Occasionally an owl or a racoon would take their toll, but these hardy birds proved they could not only survive but thrive. Knowing that these birds originally came from India , I was amazed that they could withstand the bitter cold of Cache Valley’s winters. Perhaps it helped that the farmer had a kindly wife, who would throw out some cracked corn, an occasional cup of cat food, and – on very special occasions- some hot dogs.

Peafowl are omnivores, and on this sunny day I could see them pecking away to their heart’s content in the adjacent grain fields. Luckily this band of birds avoided the fate of the six peacocks who used to free roam the zoo in Logan’s Willow Park. The zoo birds caught the bird flu virus in 2022 and all of them died.

I told my new friend, the farmer, that I was surprised how the females didn’t look the least bit like the males. The peahen is much smaller and is a rather drab brown. He explained that the peahen needs good camouflage because she lays her eggs on the ground and then has to sit there for four weeks with absolutely no help from the male.

The farmer invited me to take as many pictures as I wanted. So I pulled out my cell phone and stepped closer to the birds. That’s when I found out just how fast they can run. They stepped away and out of sight almost before I could blink. Peacocks have been clocked running as fast as 10 mph.

It wasn’t mating season, so the peacocks weren’t fanning out their tails and trying to impress the females. But I was already completely impressed to simply find out there are 200 feathers in the peacock tail. On top of that, the peacocks molt. Each year all 200 tail feathers fall out, and the peacock has to regrow them. No wonder the colors stay so bright!

This is Mary Heers and I’m Wild about all the birds who make themselves at home in Utah.

Credits:

Images Courtesy & Copyright Mary Heers, Photographer, US NPS, Pixabay and Wikimedia

Featured Audio: Courtesy & Copyright Anderson, Howe, and Wakeman.

Text: Mary Heers, https://cca.usu.edu/files/awards/art-and-mary-heers-citation.pdf

Additional Reading: Lyle Bingham, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading

Wild About Utah, Mary Heers’ Postings