Courtesy & Copyright Katie Creighton, Photographer

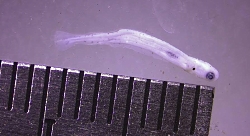

The fish nursery was built to provide the newly hatched razorbacks a way to escape the appetites of the large predators in the Colorado River.

The tiny “noodle like” larvae enter the passage, swim through a screen which holds the predators back, then live a peaceful few months in the safe, nutrient rich water of the preserve.

Courtesy & Copyright Katie Creighton, Photographer

The razorback sucker has lived in the Colorado River for thousands of years and has adapted to Utah’s warm turbid desert waters and rivers.

But during the twentieth century the razorbacks faced two threats: the growing population of non-native predator fish that consume the razorbacks, and the changing flow regime in the Colorado River Basin due to increasing water demand and development. These two threats decreased the razorbacks’ ability to maintain a sustainable population, which eventually led to the listing of the sucker as a federally endangered species.

Courtesy & Copyright Katie Creighton, Photographer

For 30 years, managers stocked razorback in the Colorado River. Then in 2008, they began noticing an increase in adult razorback numbers and detecting spawning aggregations which prompted managers to begin tracking reproduction.

Creighton explains, “We [went] into the rivers around Moab, in the Green and the Colorado Rivers, and…set larval light traps… to determine whether or not these fish were successfully spawning.”

Courtesy & Copyright Katie Creighton, Photographer

Managers could now say the razorbacks do well as stocked adults, they reproduce in the wild, and their eggs hatch successfully.

The question left unresolved is why the “young of the year” are not surviving, juvenile razorbacks are rarely seen in the wild.

Unravelling the bottleneck between when the razorbacks hatch and when they become adults has become the new focus for managers. This is where the Matheson Wetlands project came in. Utah Division of Wildlife Resources partnered with the Natural Conservancy to build the fish nursery.

Courtesy & Copyright Katie Creighton, Photographer

Phaedra Budy, professor in the Watershed Sciences Department at USU and unit leader for U.S. Geological Survey Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit said, “The Razorback sucker has intrinsic value to the [Colorado River system], is a critical member of the ecosystem, and deserves every effort for recovery.”

This is Shauna Leavitt and I’m Wild About Utah.

Building a Warm Home for Endangered Razorback Suckers’ Young-Credits:

Photos:

Courtesy US NPS, Zach Schierl, Photographer, Education Specialist, Cedar Breaks National Monument

Courtesy & Copyright Shauna Leavitt,

Audio: Courtesy and Copyright

Text: Shauna Leavitt, Utah Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Quinney College of Natural Resources, Utah State University

Building a Warm Home for Endangered Razorback Suckers’ Young-Additional Reading

Leavitt, Shauna, Piute Farms Waterfall on Lower San Juan – a Tributary of Lake Powell, Wild About Utah, Aug 6, 2018, https://wildaboututah.org/piute-farms-waterfall-on-lower-san-juan-a-tributary-of-lake-powell/

Razorback Sucker(Page 68), Utah’s Endandengered Fish, 2018 Utah Fishing Guidebook, Utah Division of Wildlife Services, https://wildlife.utah.gov/guidebooks/2018_pdfs/2018_fishing.pdf

Fish Ecology Lab, Utah State University,

https://www.usu.edu/fel/

Razorback sucker (Xyrauchen texanus), Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program, https://www.coloradoriverrecovery.org/general-information/the-fish/razorback-sucker.html

Scott M. Matheson Wetlands Preserve, The Places We Protect, The Nature Conservancy, https://www.nature.org/en-us/get-involved/how-to-help/places-we-protect/scott-m-matheson-wetlands-preserve/

A Nursery for Endangered Fish, The Nature Conservancy, https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/united-states/utah/stories-in-utah/razorback-sucker-nursery-utah/