- Utah is a wildly diverse place. Ecological and biological diversity are usually tied to an abundance of water; but here in Utah, despite our relative lack of the wet stuff, we boast of at least nine unique biomes spanning from the low-elevation Mojave Desert around St. George to the high Alpine Tundra of our many snowcapped mountain ranges. You can think of a biome as a large community of similar organisms and climates or a collection of similar habitats. Just recently, my third grade students wrapped up a semester-long investigation into seven of those biomes found in Utah including the high Alpine Tundra, Riparian/Montane Zone, Sagebrush Steppe, Wetlands, and the Great Basin, Colorado Plateau, and Mojave Deserts. We explored those biomes by way of researching a specific animal endemic in Utah to each of those biomes. We called our project “Habitat Heroes.” I’ll let a few of my students explain their findings.

- (Student readings)

- Zach’s Rubber Boa:

My name is Zach, and my animal is the rubber boa. The rubber boa lives in the riparian/montane biome in Utah. The rubber boa eats shrews, mice, small birds, lizards, snakes, and amphibians and is usually found along streams and in forests and in meadows. - Noah’s Ringtail:

This is Noah, and I’ve been studying the ringtail. The ringtail lives in the cold desert biome on the Colorado Plateau in Utah. The ringtail is gray and furry with a long black and white tail. How ringtails catch their food: number one-being very sly and waiting for the right time. They live in rocky deserts, caves, and hollow logs. - The Muskrat:

My animal’s the muskrat. The muskrat lives in the wetland biome in Utah. Muskrats live in Mexico, Canada, and the United States where there are marshes, ponds, and vegetated water. Muskrats go out at night and find food like aquatic plants, grass, and fish. They have special abilities that can be used for a very special reason to help them survive.

Head, Tongue and Scales

Courtesy & Copyright EBLS

(Full Student Name Redacted)

Courtesy & Copyright EBLS (Full Student Name Redacted)

Courtesy & Copyright EBLS (Full Student Name Redacted)

Courtesy & Copyright EBLS

(Full Student Name Redacted)

My name is Elizah, and my animal is the long-tailed weasel. The long-tailed weasel lives in the Great Basin biome in Utah. They are brown and yellow all year long except for winter. They are white during winter. [The] long-tailed weasel’s scientific name is Mustela frenata. They are mostly nocturnal.

In addition to researching the different biomes and learning about the adaptations animals must possess in order to survive there, these third graders have been visiting the several biomes local to Cache Valley and investigating their research animals’ habitats. These experiences have been powerful in helping students realize what it’s really like to exist in the wilds of Utah.

I’m Josh Boling, and I’m Wild About Utah!

Credits:

Images:

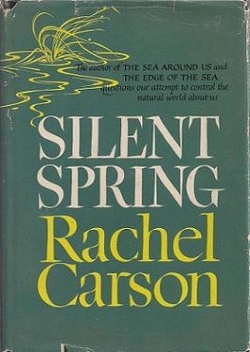

Artwork Courtesy & Copyright Josh Boling’s 3rd Grade students

Special thanks to Lisa Saunderson, Edith Bowen Lab School Art Teacher, for her help in instructing the students toward the creation of their artwork

Photos Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell, Edith Bowen Laboratory School Field Experience Director

Sound:

Text: Josh Boling, 2017, Bridgerland Audubon Society

Sources & Additional Reading

Boling, Josh and students, Habitat Heroes Explore Utah Biomes, Wild About Utah, Mar 4, 2019, https://wildaboututah.org/utah-biomes/

Edith Bowen Laboratory School, https://edithbowen.usu.edu/

Biomes, Kimball’s Biology Pages, https://www.biology-pages.info/B/Biomes.html

Mission Biomes, NASA Earth Observatory, https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/experiments/biome

The World’s Biomes, University of California Museum of Paleontology, UC Berkeley, https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/glossary/gloss5/biome/