Western Spotted Orbweaver

Neoscona oaxacensis

Courtesy & © Lyle Bingham, Photographer

Spiders on Mast for UPR Transponder Antenna

Spiders on Mast for UPR Transponder Antenna

Courtesy & © Lyle Bingham, Photographer

Spiders on Mast for UPR Transponder Antenna With Microwave Dish for Other Building Occupants

Spiders on Mast for UPR Transponder Antenna With Microwave Dish for Other Building Occupants

Courtesy & © Lyle Bingham, Photographer

Spiders on Dish for Other Building Occupants

Spiders on Dish for Other Building Occupants

Note Red Former AT&T (Now ‘American Tower’) Structure Above.

Courtesy & © Lyle Bingham, Photographer

Recently, I accompanied Friend Weller, chief radio engineer for Utah Public Radio, on a visit to what local radio engineers affectionately call Spider Mountain. We sought to determine why the Utah County translator would intermittently go off air for minutes to hours. Friend speculated that wasps or spiders were to blame. He explained that this translator receives the signal from Logan via satellite and rebroadcasts it for lower Utah County on 88.7 MHz. It is one of more than 30 translators that re-transmit UPR where mountains block the original signal.

We drove up a gravel road to the top of the dry, desert mountain known locally as West Mountain. This cheatgrass-covered mountain rises nineteen hundred feet from the waters on the south end of Utah Lake. At the base, there are fruit orchards, but climbing higher, we saw few plants rising above the cheatgrass. Near the top, more than 12 structures support antennas that transmit and relay signals across portions of Utah and Juab counties.

As we slowly climbed the gravel road in the UPR pickup, large bodies began to appear, moving on silk threads attached, like guy wires, to anything with height. Mobile spiders guarded each thread. When we passed, they took what appeared to be offensive positions. These spiders’ delicate legs easily span two inches. A unique black and white pattern of diamonds and dots on their back identifies them as western spotted orb weavers. The larger-bodied, grey spiders are females with legs attached to a three-quarter-inch body. The narrower-bodied males measure half an inch. When they move, flashes of red show on the undersides of their legs. These same spiders live along the shores of Utah Lake and the Great Salt Lake.

The exterior of the equipment building was covered with spiders, as were the transmitting antennas above and the large receiving satellite dish nearby. We could see the problem. Spiders were blocking the signal to the satellite dish feed horn. Using a broom, we gently relocated them. Many took quick exits, dropping on threads of silk from the horn to the dish below, then running to the edge and rappelling to the ground. Others took more defensive or combative positions, only to be invited off with the broom or a gloved hand. After the eviction, we sprayed around the horn and the dish supports.

On previous trips, we had often wondered what these spiders eat. This time we found small flying insects, akin to those found along the shores of Utah Lake. They are likely carried up the mountain on wind currents. Up-hill winds develop every day as the sun warms the surface of the mountain. This time of year, the spiders don’t lack nourishment.

And how did the spiders get up there? Their progenitors were also likely carried uphill on silk parachutes. Once there, the spiders found the tallest location, strung their lines, and thrived on other unfortunates delivered by the same winds. You see, spiders, like predatory birds, are helpful pest control. For a spider, hanging high above the ground on a mountain top is a great place to be. There, the spiders can catch anything that blows or flies by. No wonder they grow so large and multiply so profusely on top of Spider Mountain.

Visit Wildaboututah.org for images of the spiders hanging from the trees, guy wires, antenna masts and satellite dish. We also have links to common spiders found in Utah.

This is Lyle Bingham, and I’m Wild About Utah, Utah Public Radio and Utah’s spiders.

Credits:

Photos: Courtesy & Copyright Lyle Bingham, Photographer

Featured Audio: Courtesy & Copyright © Friend Weller, Utah Public Radio upr.org

Text: Lyle Bingham, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading: Lyle Bingham, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading

Lyle Bingham’s Wild About Utah Postings

Mitton, Jeff, Spiders disperse on strands of silk | Colorado Arts & Sciences Magazine Archive | University of Colorado Boulder

https://www.colorado.edu/asmagazine-archive/node/585

Narimanov, Nijat; Bonte, Dries; Mason, Paul; Mestre, Laia; Entling, Martin H.; Disentangling the roles of electric fields and wind in spider dispersal experiments

https://bioone.org/journals/the-journal-of-arachnology/volume-49/issue-3/JoA-S-20-063/Disentangling-the-roles-of-electric-fields-and-wind-in-spider/10.1636/JoA-S-20-063.full

Simonneaua, Manon; Courtiala, Cyril; Pétillon, Julien; Phenological and meteorological determinants of spider ballooning in an agricultural landscape – ScienceDirect

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1631069116300919

Davis, Nicky, Neoscona Tree, Lincoln Beach, Utah Lake, Utah, WildUtah.us, August 23, 2018, https://www.wildutah.us/html/insects_other/h_s_neoscona_tree.html

Davis, Nicky, Western Spotted Orbweaver a.k.a. Zig-Zag Spider-Neoscona oaxacensis Female, WildUtah.us, August 20, 2018, https://www.wildutah.us/html/insects_other/h_s_neoscona_oaxacensis_fe_west_utah_lake_20aug2018.html

Davis, Nicky, Western Spotted Orbweaver a.k.a. Zig-Zag Spider-Neoscona oaxacensis Male, WildUtah.us, August 20, 2018, https://www.wildutah.us/html/insects_other/h_s_neoscona_oaxacensis_m_west_utah_lake_20aug2018.html

Davis, Nicky, Spider at Inlet Park, Jordan River Trail, Saratoga, Utah County – Neoscona oaxacensis, Bugguide, Iowa State University, September 17, 2017, https://bugguide.net/node/view/1446087

Eaton, Eric R, Spider Sunday: Western Spotted Orbweaver, Bug Eric, February 12, 2012, https://bugeric.blogspot.com/2012/02/spider-sunday-western-spotted-orbweaver.html

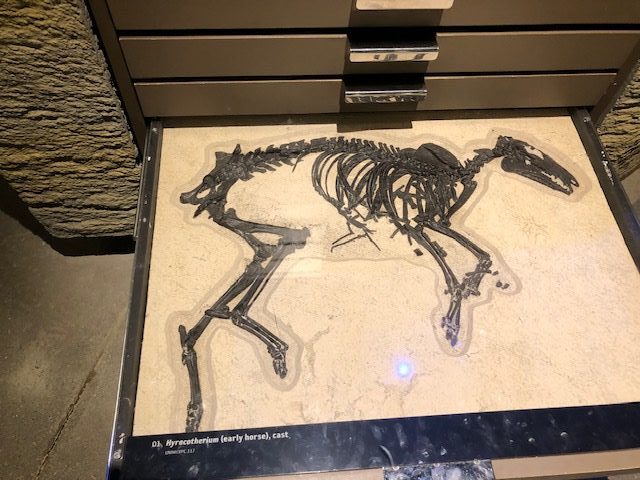

These spiders were blocking the UPR satellite signal received by the Utah County transponder broadcasting at 88.7 MHz. The spiders were identified as Western Orb Weavers, Neoscona oaxacensis, that are also found along the shores of Utah Lake and the Great Salt Lake.

Courtesy and Copyright Lyle Bingham, Photographer

More than one type of spider lives on Spider Mountain. The last time we visited Spider Mountain, we hadn’t traveled far before Friend Weller stopped the truck. A Utah tarantula was walking across the road. Yes, did I tell you the spiders on Spider Mountain are big? This guy easily covered a small dinner plate without extending its legs.

We found out that tarantulas are nocturnal and rarely seen except in August and September, when the males are searching for mates. In Utah, we found most tarantulas are identified as Aphonopelma iodius, because they have a triangular dark patch near their eye turrets. We understand our tarantulas are not to be confused with a similar brown-bodied, black-legged species, Aphonopelma chalcodes, the western desert tarantula that are found in Mexico, Arizona, and southern Utah.

Courtesy and Copyright Lyle Bingham, Photographer

Visit ‘Spider Mountain’ on https://wildaboututah.org/

Spiders in Utah, SpiderID.com, https://spiderid.com/locations/united-states/utah/

Harris, Martha, What spiders show us about mercury and the Great Salt Lake ecosystem, KUER, July 23, 2024, https://www.kuer.org/science-environment/2024-07-23/what-spiders-show-us-about-mercury-and-the-great-salt-lake-ecosystem