Courtesy Utahbirds.org/records/

Hi I’m Holly Strand.

Birders are flocking to theaters to see the new movie The Big Year. The story is based on a real life competition among birders in which they race around to count the most birds within a particular geographic boundary in a single calendar year.

To do a Big Year, you need to follow some simple rules. To count a bird it must be alive and wild and unrestrained when encountered. You have to see enough or hear enough of the bird to absolutely be sure it’s the species you are claiming to see. And the bird must be within the prescribed area and time period of your particular Big Year competition. For instance if you are doing a Big Year for the state of Utah, you can’t count a bird that you see across the border in Idaho. However, you can be standing in Idaho looking at a bird in Utah, and you can count it.

To be competitive in a Big Year you have to find ALL the usual or common birds in your designated country, state or area. This means hitting all the major birdwatching spots at critical times during the year. In Utah you might want to start in the southwestern corner of the state picking up desert species such as vermillion flycatcher and greater roadrunner . Then head to the high Uintas to see Rocky Mountain alpine and subalpine birds such as the rosy finch and northern goshawk. You’d want to check out the Great Salt Lake in all four seasons and make frequent trips up and down the Wasatch canyons as different elevation zones harbor different species. Whenever possible you should be scouring wetlands and riparian zones for whoever might be perching, wading or fishing.

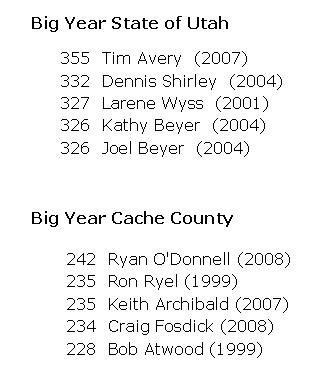

To push your count up beyond that of your competitors, you would need to spot rare birds, esp. vagrants. Vagrants are birds who have wandered or been blown off course. For example, when setting the Big Year record in Cache County, Ryan O’Donnell saw an Iceland Gull who was obviously terribly lost. And a Mexican Whip-poor-will that had somehow drifted up from Southern Arizona.

Modern communication technology is incredibly useful for locating rare birds and vagrants. Big Year participants monitor chat lists like Birdnet and BirdTalk run by Utahbirds.org. Ebird also helps spread the news of sightings. Email hotlines operate in several Utah regions. It always helps to maintain a network of birding friends who can text you the location of birds you haven’t seen yet.

Thanks to Frank Howe and Ryan O’Donnell of Utah State University’s Dept. of Wildland Resources for their assistance in developing this Wild About Utah story.

For Wild About Utah, I’m Holly Strand.

Credits:

Table: Courtesy utahbirds.org

Text: Holly Strand

Sources & Additional Reading:

American Bird Association https://www.aba.org/

Utah Birds https://utahbirds.org/

Ebird https://ebird.org/content/ebird/

Bridgerland Audubon Society Cache Birders Hotline https://www.bridgerlandaudubon.org/hotline.htm

Official movie site: https://www.thebigyearmovie.com/