Photo Courtesy & Copyright 2011

Mark Larese-Casanova

Moose Tracks in Snow

Moose Tracks in Snow

Photo Courtesy & Copyright 2011

Mark Larese-Casanova

Cottontail Rabbit Browse & Scat

Cottontail Rabbit Browse & Scat

Photo Courtesy & Copyright 2011

Mark Larese-Casanova

Hi, this is Mark Larese-Casanova from the Utah Master Naturalist Program at Utah State University Extension.

The cold depth of winter is a time when many animals are hiding- either hibernating until the thaw of spring, or finding shelter and warmth in burrows, under logs, or in the tangled branches of evergreen trees.

However, snow falls in much of Utah, and even a dusting can reveal the stories of wildlife in winter. It’s a bit like solving a mystery. By reading the clues of animal tracks, we can know not only the type of animal that made them, but also where they were going and what they were doing.

The most obvious clue is the size of a track. Smaller animals make smaller tracks, and also sets of tracks that are generally closer together.

The shape of an animal track is also very revealing. Members of the canine family, including domestic dogs, coyotes, and fox, show four toes in front, each with a visible claw. Felines, including bobcats and mountain lions, also show four toes, but no claws. Tracks from members of the weasel family, such as mink, ermine, and skunks, show five toes, each with a claw. Raccoon, squirrel, and mouse tracks almost look like they were made by tiny human hands. The long tails of some animals, including deer mice, jumping mice, and weasels, often leave a characteristic line through the center of a set of tracks.

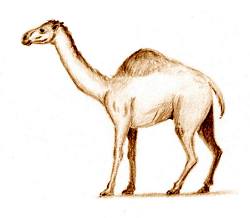

Combining the size and shape of tracks reveals further details about wildlife. The three inch long cloven hoof print of a mule deer is easily recognizable. An elk track looks almost identical, but is about four inches long. A similar moose track is even larger at six inches long.

Figuring out which animal made a track is only half of the story. If we follow tracks, we’ll surely find clues about an animal’s daily life. Wildlife often gather around sources of water that aren’t frozen, which are critical to winter survival. Perhaps rabbit tracks lead under a spruce tree where browsed branches and droppings indicate a frequent feeding spot. Maybe mouse tracks lead from tree to rock to log as it avoids owls and hawks.

While we are much more likely to see wildlife during the warmer months, winter gives us a chance to unravel the story of daily survival during the most difficult time of the year in Utah.

For Wild About Utah, I’m Mark Larese-Casanova.

Credits:

Images: Courtesy and Copyright Mark Larese-Casanova

Text: Mark Larese-Casanova

Additional Reading:

Canadian Wildlife Federation: Tracking Down Winter Wildlife. https://www.cwf-fcf.org/en/action/how-to/outside/tracking-down-winter-wildlife.html

Murie, O. J. (1982). Animal Tracks. Peterson Field Guides. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin. https://www.amazon.com/Peterson-Field-Guide-Animal-Tracks/dp/061851743X

Vermont Nature and Outdoors: Tracking Winter Wildlife. https://www.ruralvermont.com/vermontweathervane/issues/winter/97012/vins97012_tracking.shtml