Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell, Photographer

Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell, Photographer

Eric Jones closing in on the summit of Borah Peak

Eric Jones closing in on the summit of Borah Peak

Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell, Photographer

Eric Jones leading the way to Dromendary Peak in Little Cottonwood Canyon 1995

Eric Jones leading the way to Dromendary Peak in Little Cottonwood Canyon 1995

Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell, Photographer

Little Cottonwood Canyon 1991, The Thumb, S-Direct

Little Cottonwood Canyon 1991, The Thumb, S-Direct

Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell, Photographer

Eric Jones on a ledge

Eric Jones on a ledge

near the Gate Buttress

Little Cottonwood Canyon 1991.

Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell, Photographer

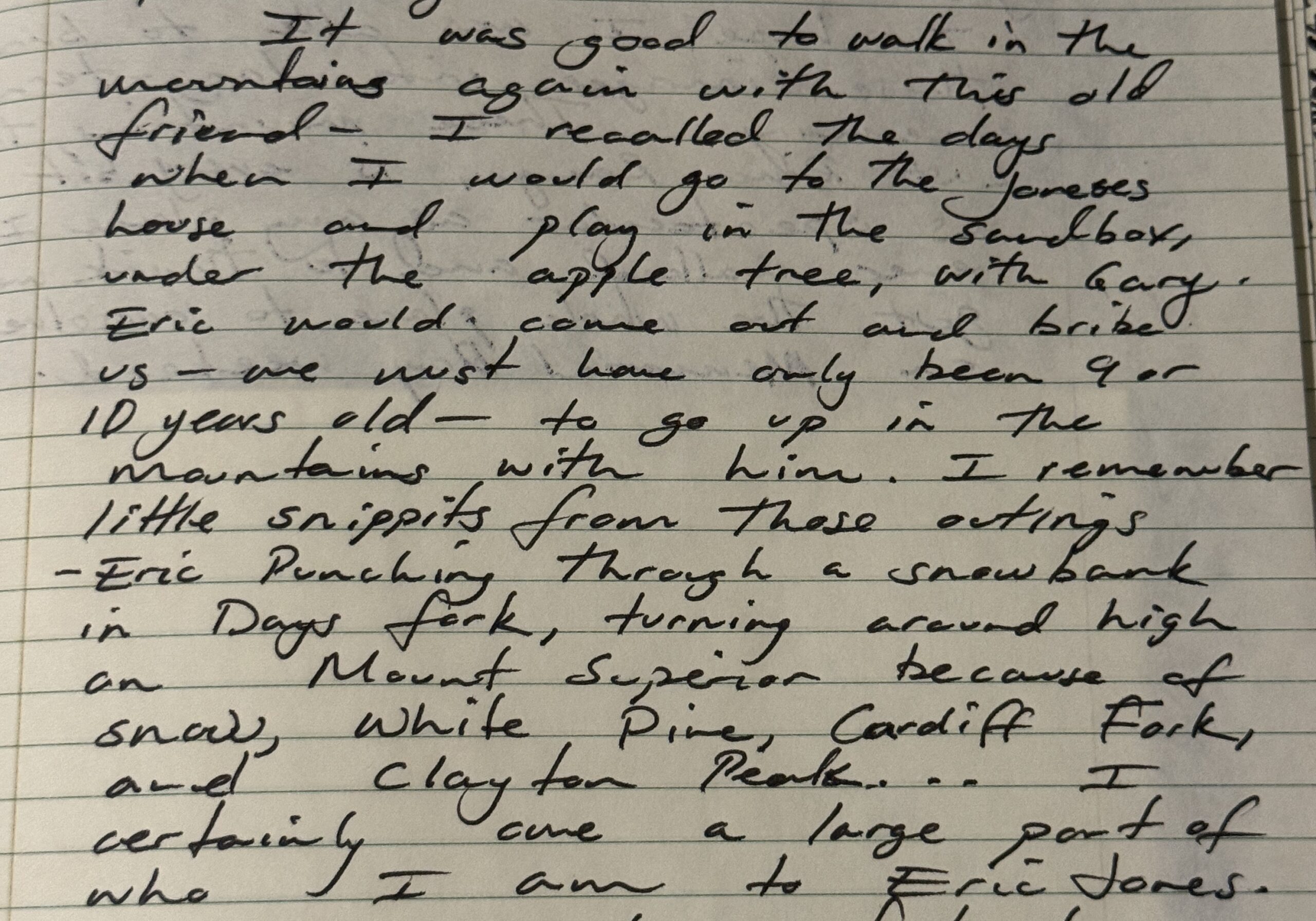

White Pine with Gary and Eric Jones circa 1988

White Pine with Gary and Eric Jones circa 1988

Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell, PhotographerI lost a beloved friend and mentor two weeks ago in a fluke canyoneering accident in Zion National Park.

I first met Eric Jones when I was four years old. My family had just moved to Sugarhouse, in the Salt Lake Valley. I rode my red, yellow, and blue Big Wheel Speedster down the sidewalk and skidded to a stop three houses away to talk to two bothers standing in their front yard. The much taller one asked if I was the new kid who just moved in. I said I was. He asked my name. I said, “Eric.” He smiled and said, “Hey, that’s my name too!” His younger brother—my age—said, “And I am Gary Jacob Jones!”

Gary and I became fast friends and Eric, five years older, was someone I perpetually looked up to. He was always taller than I, charismatic, funny, and true to himself to the core. One Saturday, while playing under an apple tree in the big sandbox in the Jones’ backyard, Eric came out to coerce Gary and I into hiking with him. We declined his initial offer but agreed when he promised 7-Eleven Slurpees on our way back. And so, we went. This scene played out many times.

Eric took us to fantastical places in the Wasatch. While we hiked, he would tell stories about wild animals, old miners’ tales, ghost stories, places he had been, and places he wanted to go. Each story, each place name, added to the intrigue and the places he talked about became the places I dreamed about: Grizzly Gulch, Sundial Peak, the West Slabs of Mount Olympus, Maybird Gulch, Cardiac Pass, Thunder Mountain, and on and on. When he described the largest Wilderness Area in the lower 48 states, the River of No Return Wilderness in central Idaho, I knew I had to get there someday. It’s a place where I have spent much of my adult life, including a long backpacking trip with Eric.

One time, he told us about an invention called a mountain bike that was a cross between a BMX bike and a ten-speed, and then, on cue, a mountain biker appeared heading down the trail. Eric drew a map of the Wasatch from memory on a blank piece of paper once, naming all the

side canyons within Mill Creek, Big Cottonwood, and Little Cottonwood Canyons. He labeled each summit, with its precise elevation. As a kid, I was amazed that all this information was just in his head, literally at his fingertips.

One June, after luring Gary and I from the sandbox once again, we attempted to climb the 11,045 foot Mount Superior. Eventually we reached a place on the knife-edge ridge where there was too much snow to safely proceed—at least for Gary and I. Eric probably could have crossed it safely and headed on to the summit, but we were his companions, and he wasn’t going to put us in danger or abandon us. So, we turned around and headed for the 7-Eleven at the mouth of Big Cottonwood Canyon.

Eric always wanted to see what there was to see around the next bend or over the next ridgeline. He planted seeds of mystery and awe in my core.

Before we were old enough to participate, Gary and I heard stories of Eric’ s feats in the mountains with the older scouts. The troop had planned a week-long 50-mile backing trip in the Uinta Mountains that included, at Eric’s instance, a layover day and extra mileage to climb Kings Peak, the tallest mountain in Utah.

When they arrived at the lake for the layover, the leaders—trail-weary from backpacking with a bunch of teenagers—announced that they wouldn’t be going to King’s Peak the next day. They would have a rest day instead. The other boys seemed happy enough to loaf around. Not Eric.

He got up before dawn, packed his day pack, and headed off to the summit on his own. I don’t recall if he woke up his tent-mate to tell him where he was going before he left or not. Either way, the leaders were not happy with him when they figured it out hours later. Gary thinks Eric was 14 years old at the time.

Eric told a funny tale from that trip. One of the other boys, Nathan Cornwall, had pre-made all his lunches for the week, which consisted of eight sardine and mayonnaise sandwiches on Wonder Bread, which he had carefully packed back in the bread sack. You shouldn’t need a food handler’s permit to know this is a horrible idea. Eric couldn’t stop laughing when he described Nathan pulling the smashed mass of soggy, stinky sardine sandwiches out of his pack the first day of the trip.

During his life Eric hiked, climbed, camped, canyoneered, skied, and rowed thousands of miles throughout west, from the Cascades to the Tetons to the red rock deserts of the southwest, and beyond. He was a keen writer and a profound thinker. He worked hard, loved deeply, and he stood for the things he believed in. He was fine friend to many.

When we were finally old enough backpack with Eric and his friends, Gary and I literally ran with our full packs on, to keep up with Eric’s long, easy strides. That’s the image I have of Eric Jones in my mind. I was just trying to keep up, chasing a legend into the wilds.

I am Eric Newell, and I am wild about people who inspire others to get outside and see what there is to see.

Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell, Photographer

Credits:

Images: Courtesy & Copyright Eric Newell, Photographer

Featured Audio: Courtesy & © Shalayne Smith Needham & Courtesy & Copyright © Anderson, Howe, Wakeman

Text: Eric Newell, Edith Bowen Laboratory School, Utah State University

Additional Reading: Eric Newell & Lyle Bingham

Additional Reading

Wild About Utah Pieces by Eric Newell

Obituary, Eric Lynn Jones, 1967-2025, https://www.memorialutah.com/obituaries/eric-lynn-jones

The Standard Thumb, Little Cottonwood Canyon, The Mountain Project-OnX&, https://www.mountainproject.com/route/105741170/the-standard-thumb

S-Direct Variant: https://www.mountainproject.com/route/105740579/s-direct-variation

Mount Borah: Peak Information and Climbing Guide, IDAHO: A Climbing Guide (Tom Lopez),

https://www.idahoaclimbingguide.com/bookupdates/mount-borah-12655/

Author’s note: “Eric also edited my Salmon River Guidebook before I sent it off to the publisher years ago. He went through it with a fine-toothed comb and picked up on so many details others missed, including myself. He influenced me to be a better writer.”

https://blackcanyonguides.com/