Courtesy US FWS

Bruce Roselund, Photographer

The natural history of the Greenback Cutthroat is fascinating! As a member of the genus Oncorhynchus, Greenback Cutthroat Trout trace their lineage back about 2 million years to Salmonid ancestors that chose to forego their return to the Pacific Ocean and instead pursued habitat further and further up the Columbia and Snake River drainages into the Green and Yellowstone River Basins. From here, cutthroat predecessors diversified into subspecies we know today: the Alvord, Bonneville, Humboldt, Lahontan, Yellowfin, Yellowstone, Colorado River, and, among others, the Greenback Cutthroat.

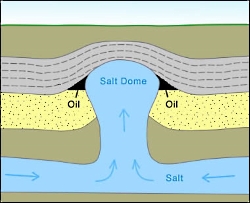

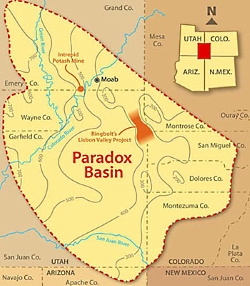

Greenbacks took a particularly arduous path to what is now their native home range. About 20,000 years ago, during the Pleistocene Epoch’s glacial maximum, Greenbacks hitched a ride via advancing ice sheets and their runoff, crossing eastward over the Continental Divide. And, historically, that’s where they’ve been found—east of the continental divide. However, in a 2014 summary report of a meeting among experts on the Greenback Cutthroat Trout’s whereabouts in Colorado, the US Fish and Wildlife Service says this about the fish’s home range: “Until recently, delineations of subspecies of cutthroat trout in Colorado were believed to follow geographic boundaries within the state, with greenback cutthroat trout on the eastern side of the Continental Divide and Colorado River cutthroat trout on the western side.” That seems to have changed.

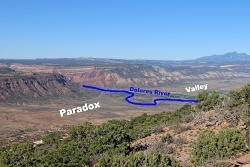

were found in Beaver Creek

in the La Sal Mountains

Greenbacks currently only occupy roughly 1% of their historic native range and were once thought to be extinct altogether. This hardy and adventurous fish refuses to call it quits, though. Who knows, maybe the valiant reclamation of its old territory has already begun along so many other inaccessible and unadulterated creek beds.

I’m Josh Boling, and I’m Wild About Utah!

Credits:

Images:

Greenback Cutthroat Trout, Courtesy Fish and Wildlife Service, US Department of the Interior, Bruce Roselund, Photographer

Beaver Creek, LaSal Mountains, Courtesy Utah Division of Wildlife Resources,

Audio: Includes audio provided by Friend Weller, UPR

Text: Josh Boling, 2018

Sources & Additional Reading

Georg, Ron, Rare trout found in La Sal Mountains, The Times Independent, Moab, UT, May 14, 2009, https://moabtimes.com/bookmark/2560140-Rare-trout-found-in-La-Sal-Mountains

Prettyman, Brett, Greenback or not wildlife officials work to expand cutthroat population, The Salt Lake Tribune, Nov. 19, 2010, https://archive.sltrib.com/article.php?id=50632061&itype=cmsid#gallery-carousel-446996

Thompson, Paul, A lifelong passion for native cutthroat trout, Wildlife Blog, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, April 10, 2017, https://wildlife.utah.gov/blog/2017/a-lifelong-passion-for-native-cutthroat-trout/

Greenback Cutthroat Trout, Western Native Trout Initiative, https://westernnativetrout.org/greenback-cutthroat-trout/

Greenback cutthroat found in Utah for first time, KSL/The Salt Lake Tribune/The Associated Press, May 1, 2009, https://www.ksl.com/?nid=148&sid=6338134