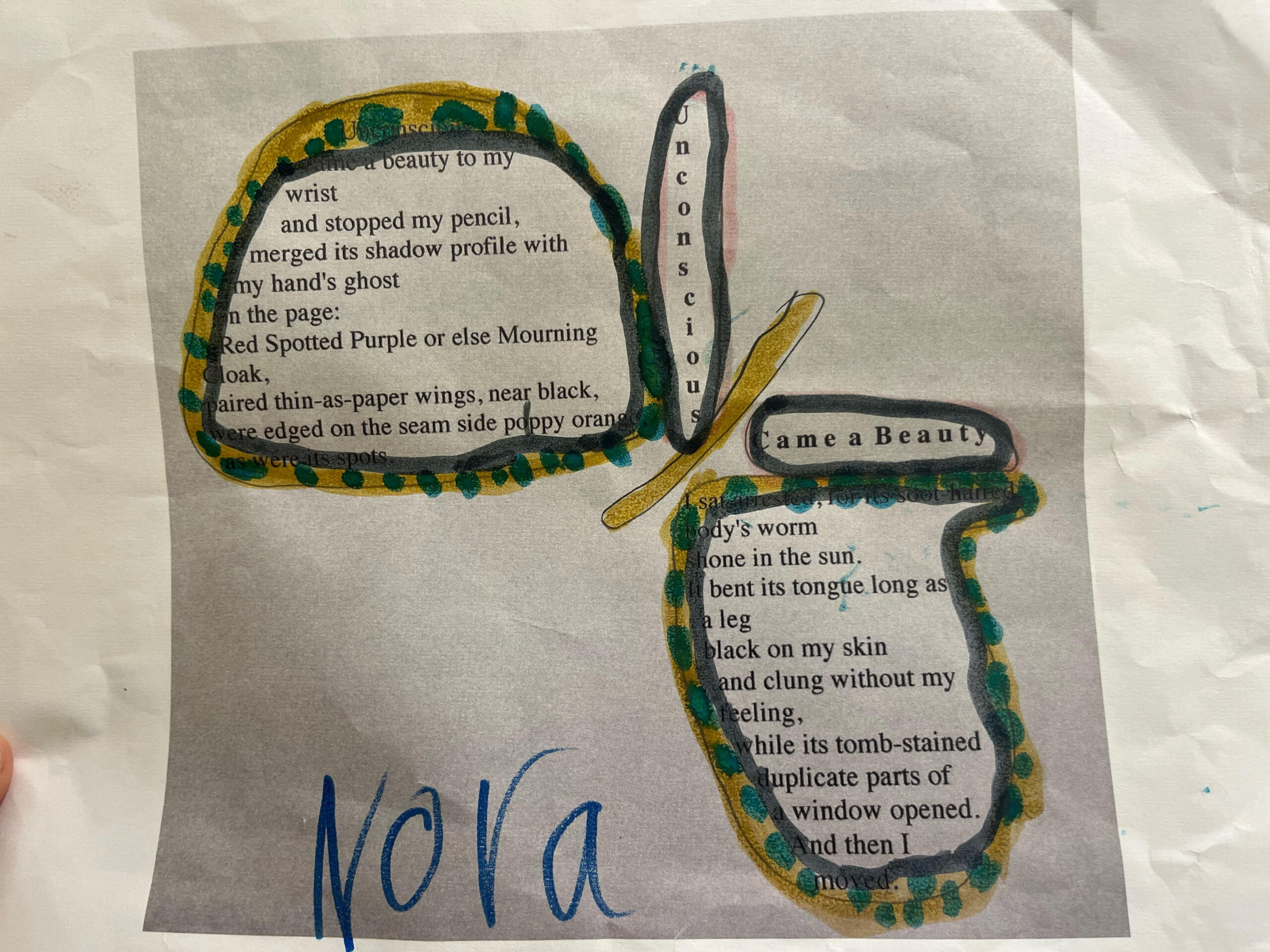

A means to emphasize the butterfly poem subject.

Poem copyright acknowledged

Photo Courtesy Shannon Rhodes

Insects? Did you say bugs? Coming into student teaching, I wasn’t too thrilled when I heard about the focus we have on bugs. From the beginning of the school year, we were already in the Logan River, digging out stonefly larva. By the second week, I was already writing a book for my students about why I do not like bugs. Here’s some of my book “Definitely NOT the Bug Girl.” I loved butterflies; they had beautiful wings. That was until I saw them closer. They looked an awful lot like grasshoppers with wings, and if you were paying attention, I hate grasshoppers! Why did I never think they were big, sticky, scary insects too? They did come from caterpillars…I should’ve known!”

Throughout the semester, from katydids flying at my head to being chased at recess with grasshoppers, I’ve grown to love the stories and discoveries the children have with bugs. Now today, I see a bug and instantly start to wonder: How did it get here? Where is it going? What would my students think about this? I could almost say I love bugs…

Courtesy & Copyright Don Rolfs 2010 https://wildaboututah.org/springs-earliest-butterflies/

Swenson’s “Unconscious Came a Beauty” captures an encounter with a butterfly. She isn’t certain about which kind of butterfly, so she offers two choices based on her descriptors. She must have been outside writing when one landed on her hand long enough for her to notice it, know it well enough to describe it.

I like how her words are in the shape of a butterfly and the wiggly way she typed the title.

When I wrote “Definitely NOT the Bug Girl,” Nora and her classmates encouraged me to include even more chapters about different kinds of insects. They wanted chapters of how I felt about roly polys, katydids, and ladybugs. I never really had an opinion about ladybugs. They were cute but a little frightening when they would fly. Finding them at recess became not so scary to me. Did you know they start their life as black and orange larvae?

- How’s this for a poem inspired by May’s shape poem?

-

Hungry crawls a lady bug larva

To our recess rock riddled with yellow aphids dots

And stopped our games

Orange-striped black

Alligator-wiggling on its six legs

We sat wondering, and Asher brought one to class

Where it crept out overnight as a familiar friend.

Courtesy & Copyright Shannon Rhodes, Photographer

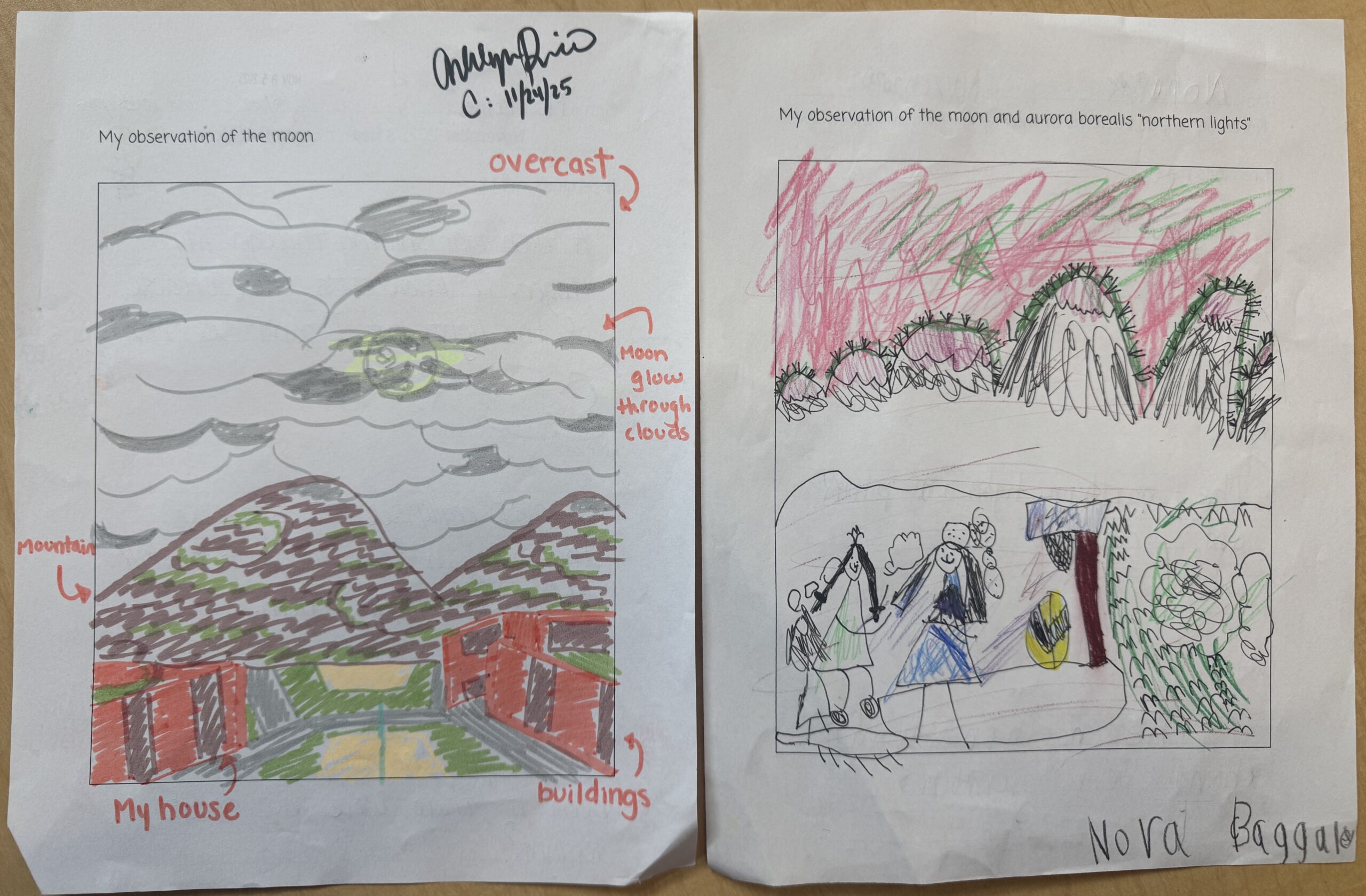

In November, every student, and teacher, was given a nature journal paper to observe the full moon that night. Sadly, the sky was full of clouds and only a faint glow was visible. Amazingly enough though, we could see the northern lights a few days later! It was a beautiful sight, and made up for missing the November Beaver Moon.

Courtesy & Copyright Shannon Rhodes, Photographer

- This is a two-voice poem we call “Witchy Sky.”

-

The beaver moon reminds me of cotton candy in the dark.

It reminds me of a flashlight shining through my finger.

The northern lights are Glinda and Elphaba.

I notice a lot of thick clouds.

I can’t really see the shape of the moon in the clouds but still it glows through them.

I wonder what does the moon feel like?

How bright would the sky have been if there were no clouds tonight?

May Swenson remembered classmates folding paper airplanes and releasing them in the classroom when their teachers’ backs were turned. In a clip from a 1969 recording “Poetry Is Alive and Well and Living in America,” she says, “My poems sail away like that, I don’t know who picks them up, who may be reading them. It’s lovely to think that people are reading my things, especially that they are being stimulated to write their own poems.”

Don’t worry, May. We are inspired by your Mourning Cloak, Ashlyn’s aphid-eaters, Nora’s night sky auroras, and students, young adult and age 6, immersed in words every day.

This is Nora Baggaley, Ashlyn Prince, and Shannon Rhodes, and we are Wild About Utah, May Swenson, night sky poetry, and of course, bugs.

Well, maybe bugs.

Courtesy & Copyright Stu Baggaley, Photographer

Credits:

Images: Classroom art Courtesy & Copyright Shannon Rhodes, Photographer

Mourning cloak butterfly (pinned), Courtesy & Copyright Don Rolfs

Nora, Shannon and Ashley in the UPR Studio, Courtesy & Copyright Stu Baggaley

Audio: Courtesy & © Friend Weller, https://upr.org/

Text & Voice: Shannon Rhodes, Nora Baggaley, and Ashlyn Prince, Edith Bowen Laboratory School, Utah State University https://edithbowen.usu.edu/

Additional Reading Links: Shannon Rhodes

Additional Reading:

BEETLES Project, The Regents of the University of California, https://beetlesproject.org/resources/for-field-instructors/notice-wonder-reminds/

Hellstern, Ron. June Fireflies, Wild About Utah, June 19, 2017, https://wildaboututah.org/june-fireflies/

Ross, Fran, 1969. Poetry is Alive and Well and Living in America. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TaKRjiqGizQ&t=1s

Spencer, Sophia with Margaret McNamara. Bug Girl: A True Story. https://www.amazon.com/Bug-Girl-True-Story/dp/0525645934

Strand, Holly. May Swenson, Wild About Utah, April 14, 2009, https://wildaboututah.org/may-swenson-a-utah-poet-and-observer-of-nature/

Swenson, May. Unconscious Came a Beauty. Poets Speak, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VO6LSVzBTKs&t=6s

Tevela, Irina. May Swenson in Space, Washington University in St. Louis, July 19, 2019, https://library.washu.edu/news/may-swenson-in-space/