Courtesy & Copyright 2009 Jim Cane

The splendid blooming meadows of summer are fulfilling their reproductive imperative now as they mature and disperse the fruits and seeds that resulted from pollination. Plants can’t walk or actively fly, so to disperse from the mother plant, seeds need to catch a ride. Wild gourds bob down flooding arroyos, thistledown floats on the wind, and red barberry fruits hope to catch the eye of a hungry song bird.

Certainly the most annoying means of dispersal is employed by seeds that stick in fur and socks. Some like cheatgrass are driven home by sharp barbed seeds that poke and hold like the porcupine’s quill. Others form evil pointy burrs, like those of puncturevine, that can flatten a bicycle tire. And then there is burdock. This European weed infests moister disturbed sites in Utah. Its burrs cling tightly to hair and clothing.

Courtesy & Copyright 2009 Jim Cane

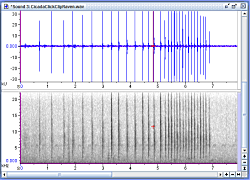

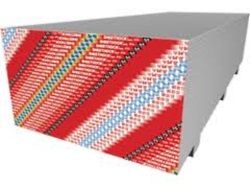

Sixty years ago, the Swiss engineer, George de Mestral, became intrigued by the seed heads of cockleburrs and burdocks. They had entangled his dog’s fur and stuck to his pant legs during a montane hunt. How did those burrs cling so steadfastly? Aided by a hand lens, you can see what de Mestral saw: ranks of hook-tipped bristles that snag clothing and fur. Burdocks inspired de Mestral’s invention of Velcro, whose patented nylon bristles are hooked over just like burdock’s and latch on just the same. When next you are beset by burdock burrs, inspect one closely and admire the inventiveness of nature. Then please terminate its dispersal by placing it where the seeds of this weed can’t germinate and grow!

This is Linda Kervin for Bridgerland Audubon Society.

Credits:

Photos: Courtesy & Copyright Jim Cane

Text: Jim Cane, Bridgerland Audubon Society

Additional Reading:

Velcro ® brand is a registered trademark of Velcro Industries B.V. www.velcro.com

Velcro USA Inc. Celebrates 50th Anniversary, (Press Release)

Invention of Velcro ® brand Fasteners, Fastech of Jacksonville, Inc., https://www.hookandloop.com/extra/inventionnew.html

Greater Burdock, Arctium lappa L. NRCS Plants Database, https://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=ARLA3

Seed Dispersal, Missouri Botanical Garden, https://www.mbgnet.net/bioplants/seed.html