Courtesy Pixabay

The first archaeological evidence we have that point to organized observances of the winter solstice come from the Neolithic period—that era from about 12,000 to 6,500 years ago which hastened the Stone Age into those of Copper and Bronze. The Neolithic coincided with the invention of farming in the Near East; and on the heels of farming came the necessity of a calendar, upon which the new agrarian economy was utterly dependent—for delineating seasons, planting and harvesting crops, and monitoring food stores over winter. We looked to the sky, of course, as we always had, for such insights into the survival of our species. We found familiar patterns there—the ebb and flow of darkness and light that came with the ever changing arc of the sun. From north to south the sun wanders, from light to dark and warm to cold. We built shrines to its movement. You know their names: Stonehenge and Newgrange; the Goseck circle and Chaco Canyon’s sun dagger. Each culture would create its own method of tracking, observing, and then of celebrating. We built tools, and then shrines, and then we built mythology.

The Neolithic agrarian economy lived by the sun. As darkness fell on wintery fields, our Stone Age ancestors shared stories about that moment when the light would return, hoping that their characters could hasten the sun. Reverence is a powerful thing. It informs the stories we tell about ourselves–stories of existence balanced on moments. We revere the return of the light when the night is at its darkest and longest. That’s when we send Raven, Maui, or an exuberant Miwok hummingbird to bring the sun back from too much darkness. That’s the mythology, at least.

Courtesy US NWS

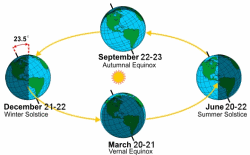

Solstice means “to be still,” to wait for the return of the light. We attach great meaning to it. The cluster of holidays we have in winter worldwide are evidence enough of that. Every culture recognizes, in its own way, the vast significance of this fleeting moment; and those observances connect us through time to the ancestors that first looked up—marking time, checking dates, counting bushels until the next harvest. The solstice is a moment we barely notice, but one that bears immense anticipation. We move right through it at the speed of time—then tell our stories to lend meaning to that time spent moving, from the light through to darkness and back again.

I’m Josh Boling, and I’m Wild About Utah!

Credits:

Photos: Courtesy US NWS

Photos: Courtesy Pixabay, https://pixabay.com/photos/snow-weather-trail-winter-autumn-834111/

Sound: Courtesy & Copyright Josh Boling & Friend Weller

Text: Josh Boling, 2018

Sources & Additional Reading

Astronomy Picture of the Day, NASA, https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap071222.html

Solstices & Equinoxes for Ogden (Surrounding 10 Years), TimeandDate.com, https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/seasons.html?n=4975

Byrd, Deborah, All you need to know: December solstice, EarthSky.org, Dec 15, 2019, https://earthsky.org/astronomy-essentials/everything-you-need-to-know-december-solstice