in the Great Salt Lake wetlands

Courtesy & © Karin Kettenring

Birds take flight

Birds take flight

in the Great Salt Lake wetlands

Courtesy & © Karin Kettenring

Wetland manager & former student

Wetland manager & former student

in the Kettenring Lab, Chad Cranney

in a stand of Phragmites australis

Courtesy & © Karin Kettenring

Rae Robinson stands in the wetlands

Rae Robinson stands in the wetlands

at Farmington Bay Waterfowl Management Area,

Courtesy & © Rae Robinson

Seeds of several native wetland plant species

Seeds of several native wetland plant species

Courtesy & © Rae Robinson

Experimental hydroseeding

Experimental hydroseeding

at Farmington Bay Waterfowl Management Area

Courtesy & © Karin Kettenring

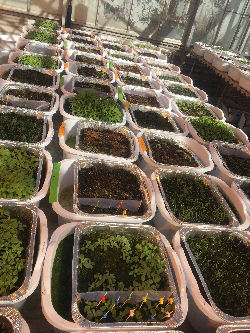

8. Seeds of several native wetland plant

Native wetland plant species

Native wetland plant species

grow in the USU greenhouse

in February 2020

Courtesy & © Rae Robinson

Revegetation field plots

Revegetation field plots

at Howard Slough Waterfowl Management Area

in June 2019,

Courtesy & © Rae Robinson

This invasive species, also known as common reed, is particularly harmful because it forms monocultures that outcompete native plant communities, diminishing quality of habitat for animal species, leaving nothing but dense tall reeds which grow 5-15 feet high.

Phragmites has spread throughout the wetlands of the Great Salt Lake, Utah and North America.

For the past decade, Karin Kettenring, professor of wetland ecology in the Department of Watershed Sciences at USU and her research team have been searching for the best methods for removing Phragmites such as grazing, mowing, or using herbicides on the invasive reed. Now they are expanding their research to find ways to restore the native wetland plant communities once Phragmites is removed.

Rae Robinson, a second-year master’s student, joined Kettenring’s research team to study native plant revegetation in Great Salt Lake wetlands.

Robinson explains, “The unfortunate part of this is native plant communities often do not return [after Phragmites has been removed] so we need to reintroduce these plants. This is where my Master’s research picks up. We are investigating: what native species to include in these revegetation seed mixes, in what proportions, and in what sowing density.”

In the summer of 2019, Robinson teamed up with the Utah Division of Forestry, Fires & State Lands and Utah Division of Wildlife Resources to begin a large-scale revegetation project in an effort to find the best methods for reseeding native plant species in Great Salt Lake wetlands.

Hydroseed was applied — a mixture of water, seed, and tackifier. The tackifier is a botanical glue used to help the seeds stay in place, it stabilizes the soil so the seeds have a much better chance of sprouting and growing.

During July and August, Robinson returned to the sites to assess the success of the seeding.

Robinson explains, “It is reasonable to think that seeding density would automatically mean a high chance of seeds taking root, but this is not always the case. At one location, a high seeding density leads to greater establishment of native species, but at another spot it does not. We are finding in seed-based restoration there is a lot of plant mortality, or loss. We are asking: Why is that? What causes this failure in restoration? And what are the best ways to establish diverse native plant communities?”

During the winter months Robinson evaluated some new species in the USU greenhouse – these are potential candidates for restoration that might perform better than the species tested in 2019. Results of this preliminary greenhouse trial suggest that nodding (Bag-er-tick) beggartick, golden dock, and fringed willowherb may grow more readily than the previous species evaluated. These three species will be included in experimental revegetation mixes this summer.

The end goal of Robinson’s research is to determine best practices for seed-based revegetation in wetlands and provide better information for wetland managers faced with the challenge of restoring native plant communities.

The restoration of native plant communities in Great Salt Lake wetlands will improve the quality of habitat for birds and enhance the many ecosystem services these wetlands provide.

This is Shauna Leavitt and I’m Wild About Utah.

Credits:

Photos: Courtesy & Copyright © Rae Robinson, Courtesy & © Karin Kettenring

Text: Shauna Leavitt, Utah Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Quinney College of Natural Resources, Utah State University

Sources & Additional Reading

Leavitt, Shauna, Our Invasive Phragmites, Wild About Utah, March 11, 2019, https://wildaboututah.org/our-invasive-phragmites/

Leavitt, Shauna, The Invasive Phragmites, Wild About Utah, April 16, 2018, https://wildaboututah.org/invasive-phragmites/

Rupp, Larry, et al, Phragmites Control at the Urban/Rural Interface, Utah State University Extension, September, 2014, https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1688&context=extension_curall

Larese-Casanova, Mark, Phragmites-Utah’s Grassy Invader, Wild About Utah, August 23, 2012, https://wildaboututah.org/phragmites-utahs-grassy-invader/

Muffoletto, Mary-Ann, Mighty Phragmites: USU Researcher Studies Wetlands Invader, Utah State University Extension, June 18, 2009, https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1688&context=extension_curall

Common Reed, Phragmites australis, Utah State University Extension, https://extension.usu.edu/rangeplants/grasses-and-grasslikes/common-reed

Duncan, Brittany L., et al., Cattle grazing for invasive Phragmites australis(common reed) management in Northern Utah wetlands, Utah State University Extension, https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3038&context=extension_curall