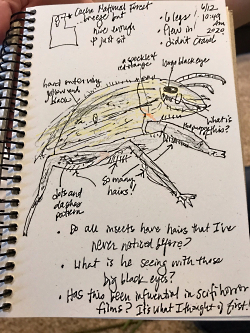

Courtesy & © Rob Soto

Used with permission

I was driving home from work on a small back road as I usually do to avoid traffic. As I was heading north, two juvenile robins swooped down across the road as they normally do in the path of an oncoming red truck. The first robin managed to cut upwards fast enough to dodge the truck’s hood, but the second broadsided the truck, hitting its door, and fell to the ground crumpled.

I slowed down and looked out my window at the bird writhing in the median of the road, and something inside of me happened that I cannot explain. I pulled over, went over to the convulsing bird, and quickly ferried him to a grassy patch on the shoulder underneath a tree. I hopped back in my car, and continued my drive home. The young robin passed from my mind.

As I arrived home, I decided to kick my feet up with my partner in the backyard and unwind by watching our young dogs play. We call it Dog TV. It’s a hoot. I saw a robin perch and sing on the roof of my garage, and the young broken robin from my drive home re-entered my mind.

I began to wonder if he was ok. I asked my partner if I should go back and check on him.

There were three options I settled on as to his state, and the need for my checking in. Perhaps he was just stunned by the impact and would’ve recovered quickly and wouldn’t be there, easing my mind. Perhaps he was in fact injured beyond saving and would not recover and so it was my responsibility to end his suffering myself. The last option was that he had already passed, and so I would take his body so that it could be buried, or at least given to the crows. I wouldn’t want to be left on the side of the road as a finality, and I doubted he would either.

I asked my partner: do I go and see to an end if any, or leave his fate be?

She thought about this for a moment and finally declared that I should let nature be nature, and to leave him be.

At first, this was not the response I had wanted. Inaction does not suit me, and so I argued this in my head. But am I not nature, too? Can I not act as that agent of nature being nature and choose to do my diligence, to either see that he survived, give him an end, or commit his body back to the world?

I took a breath and decided to pivot my reflection towards my inability to pass the bird by initially. Though the thought did occur to me to pass him by, I experienced that I could not from a visceral place, not the mind. I reacted, and the instinct of care I felt upon seeing this bird could not be suppressed.

I came to a conclusion. What was this instinct of mine but nature being nature? Why did it trigger but as a sign of my own agency as a natural being? Who am I to assume that only I could carry out being an agent of compassion? If this instinct was natural for me, then it is natural for others, and thus could be realized by anyone. This realization gave me hope.

I decided that I was nature being nature, a human being compassionate, and chose to trust the rest of the world to be so with gentle caring, too. I chose to see what I cannot control with goodness, and allow myself to remain abdicated of my control. I chose to have faith that, if I could be struck and pulled to empathetic action from my animal gut, others would too.

I broke my contemplation, and agreed with my partner that I would let nature be nature.

We turned our attention back to our dogs playing, and the robins kept singing. Life continued to be good, even in the face of the unknown.

I’m Patrick Kelly and I’m Wild About Utah.

Credits:

A Moral Dilemma

Images: Images Courtesy & Copyright Rob Soto, Artist, all rights reserved

Audio: Contains audio Courtesy & Copyright Kevin Colver

Text: Patrick Kelly, Director of Education, Stokes Nature Center, https://logannature.org

Included Links: Lyle Bingham, Webmaster, WildAboutUtah.org

Additional Reading

Bengston, Anna, American Robin, Wild About Utah, January 18, 2016, https://wildaboututah.org/american-robin-160118/

Bengston, Anna, Robins in Winter, Wild About Utah, March 13, 2014 (Repeated February 2, 2015), https://wildaboututah.org/robins-winter/

Bingham, Lyle, Richard Hurren(voice), The Occupants on Robin Street, Wild About Utah, July 8, 2008, https://wildaboututah.org/the-occupants-on-robin-street/

Wildlife Rehabilitation, Bridgerland Audubon Society, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/birding-tools/wildlife-rehabilitation/