much better during hibernation

because it has a larger body

compared to the area of its outer

surface and it has thicker fur

compared to smaller animals

Photo Courtesy US FWS

Mike Bender, Photographer

Mountain Chickadee

Even though some small birds, like chickadees, may enter torpor,

they use almost all of their

energy stores each night.

Courtesy & Copyright

Photographer: Stephen Peterson

Hi, this is Mark Larese-Casanova from the Utah Master Naturalist Program at Utah State University Extension.

While I’ve mentioned how certain animals are well adapted to being active in winter, some choose to save their energy and sleep the winter away. Maintaining a constant body temperature in winter, when air temperature is relatively low, can require consuming great amounts of energy stores, such as fat. This can be especially difficult during a time of year when food is scarce.

Smaller animals especially struggle with heat loss because, relative to their body size, they have much more surface area from which they can lose heat. Compare a mouse to a bear- the bear will retain heat much better because it has a larger body compared to the area of its outer surface. Not to mention, a bear’s fur is much thicker than that of a mouse!

For certain animals, it makes sense to lower body temperature while being inactive so that they can conserve as much energy stores as possible. This can happen in several different ways. Sleeping for part of a daily cycle can conserve a little energy since body temperatures drop slightly during sleep. If air temperatures are particularly low and food is scarce, some animals will enter torpor, allowing their body temperatures to drop closer to air temperatures in order to save even more energy. An animal can be in torpor for just a night, or perhaps a few days. If it is able to store enough energy reserves and can survive a decrease in body temperature for longer periods, some mammals may enter deep torpor and hibernate for several weeks or months in the winter. During this time, the rate of energy consumption is just a small fraction of what it might normally be when the animal is active.

Body size and energy stores influence just how inactive an animal can be in winter. Some of our smallest mammals, such as shrews and mice, lose heat so readily and can store so little fat that they cannot afford to hibernate. They must always find food in order to survive. Even though some small birds, like the black-capped chickadee, may enter torpor, they use almost all of their energy stores each night. If they fail to replenish their fat reserves each day, they might not survive.

The true hibernators are the mid-sized mammals. While ground squirrels, jumping mice, and bats may hibernate for much of the winter, they occasionally wake up for a day or two of activity. Even larger mammals, including raccoons, skunks, and bears, don’t actually need to hibernate. Their body temperature drops just a little, and they are able to survive on their stored fat simply by sleeping.

So, while I sometimes envy the true hibernators on some of those cold winter days in Utah, I’m still thankful that I can adapt to winter and enjoy our great outdoors year-round.

For Wild About Utah, I’m Mark Larese-Casanova.

Credits:

Images: Courtesy US FWS and Stephen Peterson, Bridgerland Audubon Society

Text: Mark Larese-Casanova, Utah Master Naturalist Program at Utah State University Extension.

Additional Reading:

Heinrich, B. (2009). Winter world: The ingenuity of animal survival. Harper Perennial.

Eckert, R., D. Randall, and G. Augustine. Animal physiology: Mechanisms and adaptations. W. H. Freeman and Company.

Red Butte Wilderness, Utah

Red Butte Wilderness, Utah

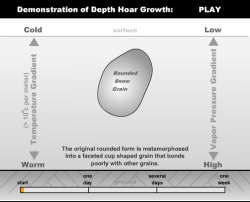

Depth Hoar

Depth Hoar