Gopherus agassizii

Courtesy & Copyright 2009

Kevin Durso, Photographer

Adult Desert Tortoise

Adult Desert Tortoise

Gopherus agassizii

Courtesy & Copyright 2009

Kevin Durso, Photographer

Adult & Juvenile Desert Tortoise

Adult & Juvenile Desert Tortoise

Gopherus agassizii

Courtesy & Copyright 2009

Andrew Durso, Photographer

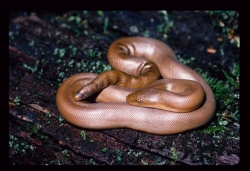

Juvenile Desert Tortoise

Juvenile Desert Tortoise

Gopherus agassizii

Courtesy & Copyright 2009

Andrew Durso, Photographer

Tortoises are turtles that live their whole lives on land. Most tortoises are native to Africa and South America, but several are North American including the Desert Tortoise whose range extends to southwestern Utah. Their shells consist of enlarged scales called scutes. These scutes are tan, black, or dull orange, and etched with many concentric lines, like the growth rings of a tree. Desert Tortoises look like grizzled old men, even the Oreo-sized hatchlings, which over several decades will grow to football size.

Desert Tortoises mate in the spring, and a few months later, the female lays her 5 or 6 eggs in a funnel-shaped pit dug in the sand. The sex of the baby Desert Tortoises is determined by the sun’s heating rather than by genetics – cooler incubation yields males, hotter eggs produce females, with a mix of sexes developing at intermediate temperatures.

Desert Tortoises primarily eat the flowers of desert plants such as globemallow and threeawn. Because most desert plants only bloom briefly each spring, tortoises must eat a lot between April and June, although they can be active during all but the coldest months. Being toothless, they grind up their vegetarian fare using a specialized bone embedded in their jaw muscles. Like cows and other herbivores, they depend on microbes in their gut to digest the cellulose in their diet. Even more than food, water is precious to a Desert Tortoise. They have little to spare, sometimes going for months without urinating, but will pee defensively if handled. Resist the temptation to pick them up or you will rob the poor animal of its water supply for the entire year.

Once found throughout the Mojave and Sonoran deserts, Desert Tortoises are much less common than they were a century ago. They have not fared well with urbanization, highways, and off-road vehicle traffic. An upper respiratory tract disease can also be lethal, especially when crowded or stressed, as in captivity. Desert Tortoises are now protected by the US Endangered Species Act.

Today’s program was written by Andrew Durso of USU’s biology department.

Credits:

Theme: Courtesy & Copyright Don Anderson Leaping Lulu

Images: Courtesy & Copyright Andrew Durso and Kevin Durso

Text: Andrew Durso, https://www.biology.usu.edu/htm/our-people/graduate-students?memberID=6753

Additional Reading:

Gopherus agassizii, Turtle Conservancy, https://www.turtleconservancy.org/news/tag/Gopherus+agassizii

Grover, Mark C., DeFalco, Lesley A, Desert Tortoise(Gopherus agassizii): Status-of-Knowledge, Outline With References, USDA, 1995, https://www.fs.usda.gov/research/treesearch/30627

Desert Tortoise, Gopherus agassizii, Mojave National Preserve, https://www.mojavenp.org/Gopherus_agassizii.htm

Gopherus agassizii (COOPER, 1861), The Reptile Database, Peter Uetz and Jakob Hallermann, Zoological Museum Hamburg,

https://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/species?genus=Gopherus&species=agassizii

Desert Tortoise, Species, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Utah Department of Natural Resources, https://fieldguide.wildlife.utah.gov/?species=gopherus%20agassizii

Desert Tortoise Information and Collaboration, Mojave Desert Ecosystem Program, https://www.mojavedata.gov/deserttortoise_gov/index.html

Red Cliffs Desert Reserve, http://www.redcliffsdesertreserve.com