Courtesy & Copyright Jeremy Jensen

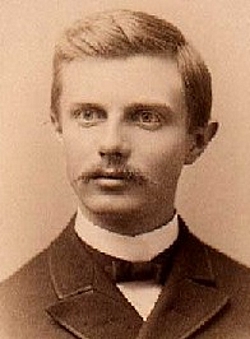

Sculpin

Sculpin

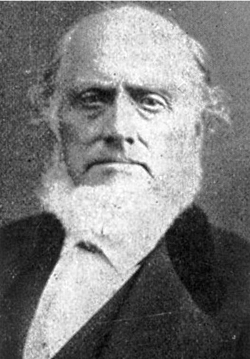

Courtesy & Copyright Jereme Gaeta

Bear Lake Sculpin

Bear Lake Sculpin

Courtesy & Copyright Jeremy Jensen

Sculpin in Haley Glassic’s hand

Sculpin in Haley Glassic’s hand

Courtesy & Copyright Jeremy JensenIn Bear Lake, there lives a small, bright blue eyed, bottom-dwelling fish species that may appear insignificant as it moves among the lake’s cobble areas.

The fish grows up to three inches in length and is endemic to Utah’s northern most lake, hence its name – the Bear Lake sculpin.

The sculpin is a scale-free, tadpole-like fish with a broad flat head, a slender body and eyes placed high on its head. It has elaborate pectoral fins that stretch out like decorative fans from both sides of its body and two dorsal fins along its back that sometimes connect at the base.

Although the sculpin is small, its worth is significant. One of the main sportfish of Bear Lake, the Bonneville Cutthroat trout, rely heavily on the sculpin to be a source of food as its main forage fish, the sculpin makes up more than 70% of the diet for juvenile trout.

Interestingly, Bear Lake is the only place the sculpin is natively found and it is one of only two sculpins in the West that live in deep-water lake habitats.

It stays exclusively in the lake. While other fish in Bear Lake migrate up the tributaries to spawn, the sculpin seek out the lakes cobble areas where it can find cavities under and between the rocks to lay its eggs.

The best cobble habitat in Bear Lake is along the eastern shore at Cisco Beach where the shallow water covers the rounded rocks that range from 2-12 inches in size. Only 0.1% of Bear Lake is cobble habitat.

The shallow location of the cobble is important for the successful nest since the wave turbulence begins the hatching process. Waves and currents also help with the dispersal of the sculpin embryos throughout the 282 square kilometer lake.

Once hatched the young-of-the year have a feeding ritual quite different from their juvenile and adult counterparts. While the older sculpin stay on the bottom of the lake foraging for food, the young float up during the day to where the sun easily penetrates the water. The sunlight makes it easier for the young sculpin to find their food and it warms their bodies so they can digest their food more rapidly– which stimulates growth. The young sculpin can feed up to nine times faster during the day than they would at night. Once they have grown, it is difficult for sculpin to rise up the water column because they do not have swim bladders as trout do.

An essential component to have a large population of new sculpin each year is to ensure there is sufficient cobble habitat in Bear Lake.

When drought years hit, large portions of the cobble are exposed due to both that drought and human use. While the lake has never dropped to the level where all cobble habitat is exposed, a USU research team has documented more than 96% of cobble reductions during extreme multi-year drought events. This raises major concerns and questions about how a decrease in cobble would impact the sculpin population.

To investigate this question, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources awarded a research grant to Jereme Gaeta, assistant professor in the Department of Watershed Sciences and the Ecology Center in the Quinney College of Natural Resources to improve our understanding of the potential effects of drought on cobble habitats and fish communities.

Hayley Glassic, a graduate student in Gaeta’s lab has worked on this project since 2015. In the coming months their findings will be published and made available to the public.

This may be important reading for any agency or person making decisions about the Bear Lake water levels, which would impact the cobble habitat of the Bear Lake sculpin.

According to Glassic, “Sculpin appear to be one of the essential parts of the entire (Bear Lake) ecosystem.” Ensuring their cobble habitat is preserved during drought years is necessary for the overall health of the lake’s ecosystem.

This is Shauna Leavitt for Wild About Utah.

Credits:

Theme: Courtesy & Copyright Don Anderson Leaping Lulu

Photos: Courtesy and Copyright Jeremy Jensen

Photos: Courtesy and Copyright Jereme Gaeta

Text: Shauna Leavitt

Voice: Shauna Leavitt

Sources & Additional Reading

Bear Lake Sculpin – Cottus extensus, USGS, https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/factsheet.aspx?SpeciesID=503

Clyde Lay, Wayne A Wurtsbaugh, and James R Ruzycki, Reproductive ecology and early life history of a lacustrine sculpin, Cottus extensus (Teleostei, Cottidae)

Bear Lake Sculpin – Cottus extensus, Fishbase Consortium, https://fishbase.org/summary/Cottus-extensus.html

Bear Lake Sculpin – Cottus extensus, Species, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Utah Department of Natural Resources, https://fieldguide.wildlife.utah.gov/?species=cottus%20extensus

Bear Lake Blue Ribbon Fishery, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, https://dwrapps.utah.gov/fishing/fStart?NA=Bear%20Lake%20(Blue%20Ribbon) [Link updated January 2024]

Bear Lake Sculpin – Cottus extensus, Idaho Fish & Game, https://idfg.idaho.gov/species/taxa/20071 [Link updated January 2024]