Courtesy & Copyright Joseph Kozlowski, Photographer

Silent whisper-yells bombard, as if I’m a paparazzi capturing exclusive, behind the scenes footage of Taylor Swift or some other super star. However, these are kid whispers, and I’m just a 2nd-grade teacher leaning out my exterior classroom door, taking pictures of a curious little Black-Capped Chickadee happily pecking seeds from our class millet feeder which dangles just outside our window.

I happily comply with the entourage’s request and snap picture after picture of the little black and white songbird.

Courtesy & Copyright Joseph Kozlowski, Photographer

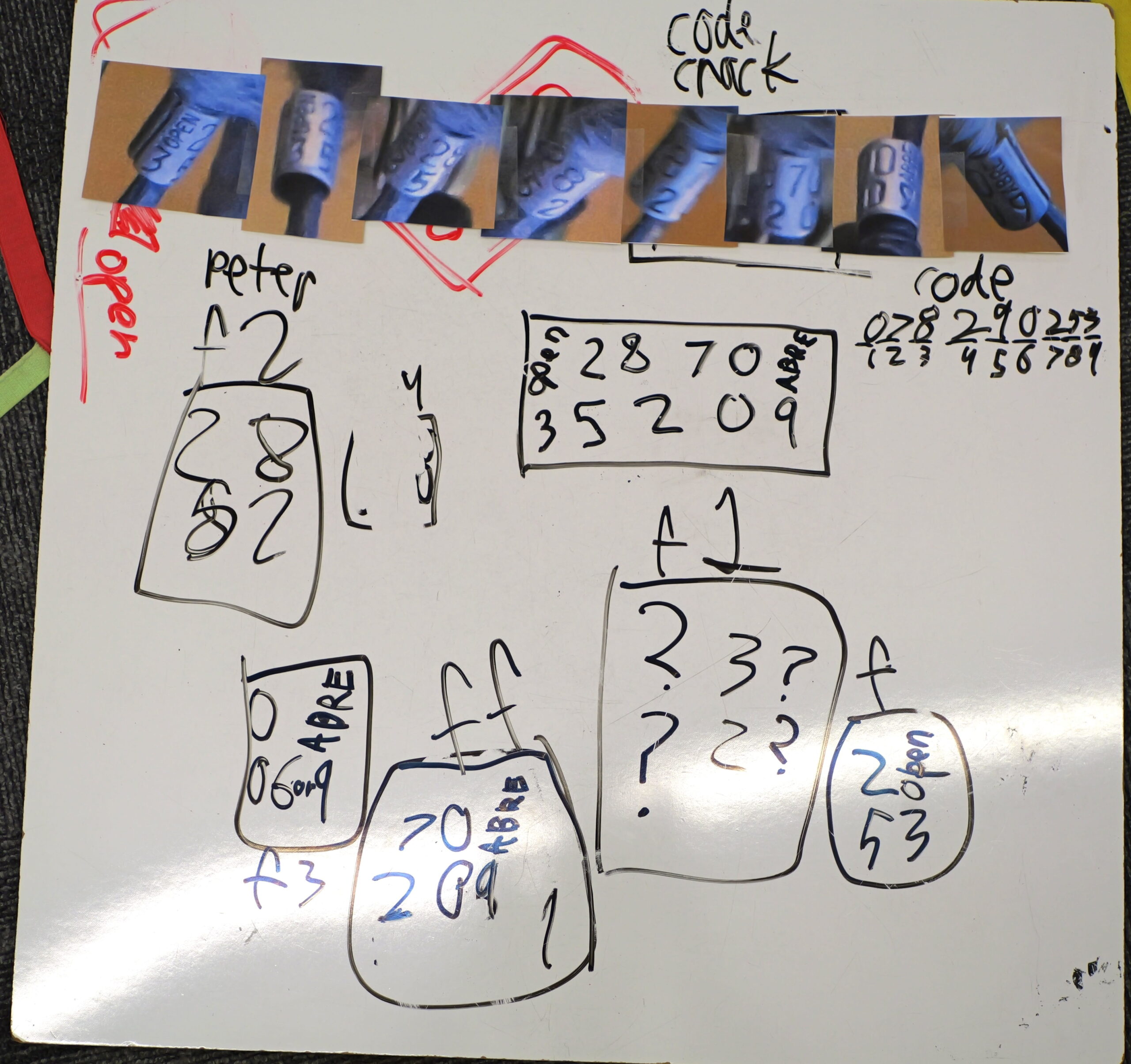

“Cracking the Code”

“Cracking the Code”

Leg Band Analytic Cyphers

Courtesy & Copyright Joseph Kozlowski, Photographer

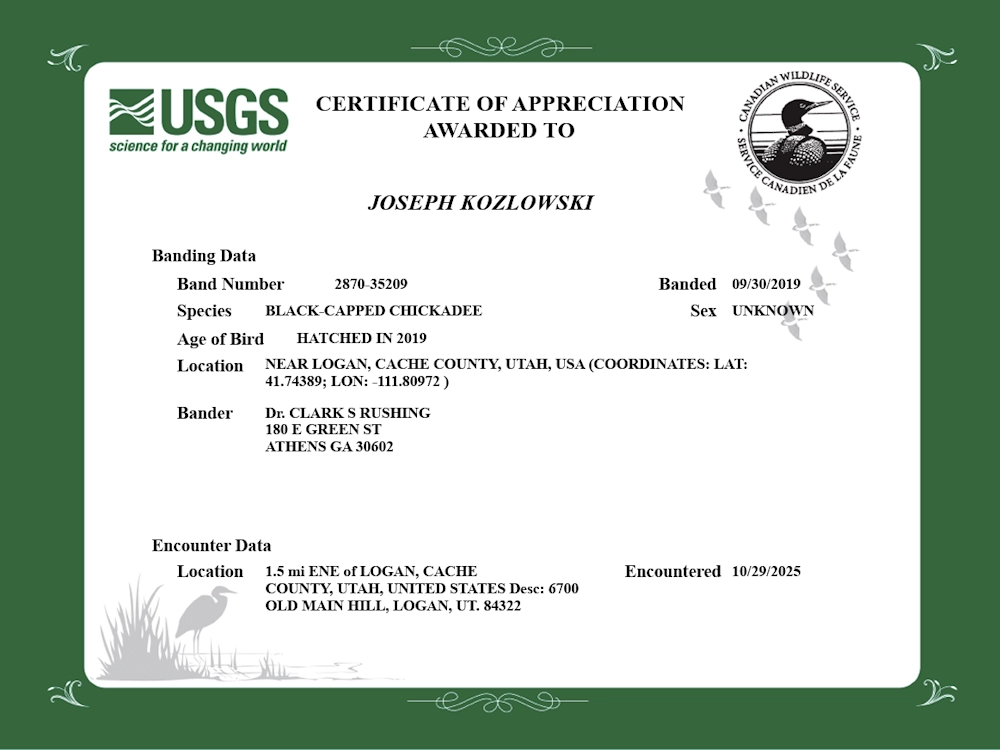

Bird Banding Certificate of Appreciation USGS

Bird Banding Certificate of Appreciation USGS

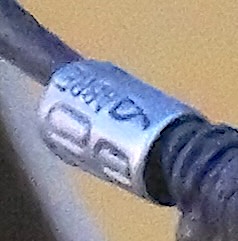

Courtesy & Copyright Joseph Kozlowski, Contributor & PhotographerEventually it flies away and I return to class and connect the camera to our large screen so students can see the close-up pictures of our little friend. I display the images and voices erupt from the students “Look at its leg! There is something shiny stuck on it!”

Sure enough, a metallic band encircled its right tarsometatarsus (fancy word for lower leg).

We zoomed into the picture and students noticed faint numbers and letters. They asked to see the various other pictures I had captured. The band was visible in each picture. Additionally, a different perspective of the band was visible in each picture based on the way the bird had adjusted its body between shots.

The students had an idea. Zoom into the band of each picture and print them. Each picture would have the band from a different angle, which may allow them to ‘crack the code’ of the specific 9-digit identification number that was encrypted upon it.

I did as the kids suggested. Soon kids were madly puzzling around the room, moving pictures from here to there, trying to see what clue from one angle of the band might inform a clue from a different angle of the band. It was a complex puzzle, but they wouldn’t give up.

A kid yells out, “We got it!” and everyone rushes over to their large whiteboard, which by this time, looks like a rocket scientist has been planning the next launch.

[287035209] was inscribed on their whiteboard

We accessed the United States Geological Survey (USGS) website for reporting banded birds and entered the number along with associated data.

Up popped a corresponding specimen:

Species: Black-Capped Chickadee

Banded: 2019

Scientist: Dr. Clark Rushing

Location: Cache County, USA

Students cheered and shouted when they read the information, and were most excited to learn how old our little friend was. They quickly decided looking up Dr. Rushing (now a professor at University of Georgia) and emailing him was necessary and formulated a message sharing their experience.

To our surprise, Dr. Rushing responded to the students sharing his memory of the banding project and how a 7-year-old Black-Capped Chickadee was a very rare scientific discovery.

The students sat with amazement, feeling like real scientists. Leaving the classroom that day for carpool, I hear a little girl giggle, pull her friend over, and whisper in her ear, “One day, I’m going to be a bird scientist just like Dr. Clark Rushing!”

This is Dr. Joseph Kozlowski, and I am wild about outdoor education in Utah!

Credits:

Images: Courtesy & Copyright Joseph Kozlowski, Photographer, Used by Permission

Featured Audio: Courtesy & Copyright © Kevin Colver, https://wildstore.wildsanctuary.com/collections/special-collections/kevin-colver and including contributions from Anderson, Howe, and Wakeman.

Text: Joseph Kozlowski, Edith Bowen Laboratory School, Utah State University https://edithbowen.usu.edu/

Additional Reading Links: Joseph Kozlowski & Lyle Bingham

Additional Reading:

Joseph (Joey) Kozlowski’s pieces on Wild About Utah:

Reporting a bird with a federal band or auxiliary marker, U.S. Geological Survey(USGS), U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.usgs.gov/labs/bird-banding-laboratory/science/report-a-band

The USGS serves as the primary science bureau for the DOI, integrating geological, hydrological, and biological research to support decision-making on public lands. Who We Are: https://www.usgs.gov/about/about-us/who-we-are#:~:text=What%20We%20Do,features%20available%20to%20the%20public.