Courtesy &

Copyright 2010 Holly Strand

Hi, I’m Holly Strand from Stokes Nature Center in beautiful Logan Canyon.

Common Mullein , Our Lady’s Flannel. Velvet Plant. Clown’s Lungwort. Jupiter’s Staff. Shepherd’s Clubs. Beggar’s Blanket. Hare’s Beard, Bear’s ear, and Nature’s Toilet Paper. These are just a few of the names that apply to a single species that is a widely distributed across Europe and Central Asia and naturalized in North America.

Common names are descriptive and often charming, but they are local names and won’t be understood beyond their particular region or in another language. And sometimes common names are downright misleading. For example a koala bear isn’t a bear. And a red panda isn’t a panda.

To avoid confusion, scientists use a unique two word designation—usually taken from Latin or Greek – to identify a species unambiguously. The first word is the name of the genus to which the organism belongs. The genus comprises a group of closely related animals or plants. The second term is chosen by the person that describes and publishes the species account.

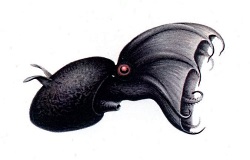

“vampire squid from Hell”

Illustration by Carl Chun 1911

Public Domain/expired copyright

It is a huge breach of etiquette to name a species after yourself. But the taxonomist can name the organism after the person who actually found it in the field. An example is Mentzelia shultziorum, a blazingstar named after Utah botanist Leila Schultz who first found the plant in Professor Valley in Grand County. Taxonomists can also name the species after a friendly colleague and then hope that the friendly colleague will name one after them.

Often the name will describe some physical characteristics of the species. Earlier this year, a paleontologist unearthed a new dinosaur here in Utah and named it Jeyawati rugoculus. That’s a combination of Zuni and Latin for “grinding mouth, wrinkle eye.”

Other names are based on location: Penstemon utahensis is a penstemon found in our state. Amblyoproctus boondocksius is a scarab, and was apparently found in the middle of nowhere.

Often the name will represent a subjective reaction toward the organism. Vampyroteuthis infernalis translates into “vampire squid from Hell”, Indeed it is rather scary looking cross between a squid and an octopus.

Some scientists get sentimental at naming time. They’ll name species after their loved ones. Or their favorite artists. Thus we have 2 trilobites in the Avalanchurus genus named lennoni and starri. McCartney and Harrison are honored in a neighboring genus.

I’m proud to say that a Utah biologist named a parasitic louse, Strigiphilus garylarsoni. The Far Side cartoonist should not take offense. In a letter to Larson, Dr. Dale Clayton praised him for “the enormous contribution that my colleagues and I feel you have made to biology through your cartoons.”

For sources and archives of past programs see www. Wild About Utah.org

For Wild About Utah and Stokes Nature Center, I’m Holly Strand.

Credits:

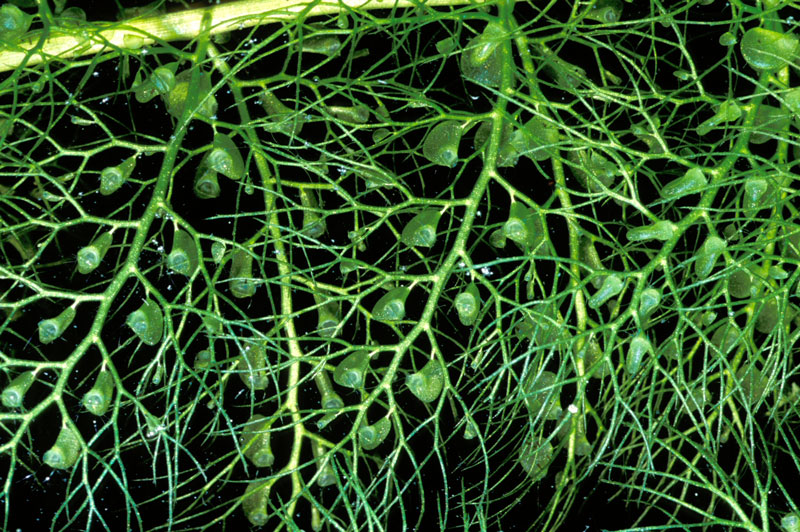

Photo: Mullein-Courtesy & Copyright 2010 Holly Strand

Squid Illustration Carl Chun 1911 (Public Domain Courtesy Wikimedia.org)

Text: Stokes Nature Center: Holly Strand

Sources & Additional Reading

Gotch, A.F. 1996. Latin Names Explained: A Guide to the Scientific Classification of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals. NY: Facts on File, Inc.

Isaak, Mark. Curiosities of Biological Nomenclature website. https://www.curioustaxonomy.net/rules.html [Accessed September 15, 2010]

O’Donoghue, Amy Joi. 2010. ‘Grinding mouth, wrinkle eye’ is name of newly discovered species dinosaur. Deseret News, May 27, 2010.

Prigge, Barry A. 1986. New Species of mentzelia (Loasaceae) from Grand County, UT. Great Basin Naturalist Vol. 46, No. 2 pp. 361-365