Aquila chrysaetos

Courtesy Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Northern Utah (WRCNU.org)

Elk Bath

Elk Bath

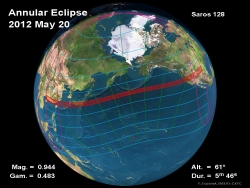

From a 2000 fire in the

Bitterroot National Forest in Montana

Courtesy Wikimedia &

USDA Forest Service

John McColgan, Photographer

Hi, I’m Holly Strand.

You may have heard about the golden eagle nestling that was badly burned during a recent Utah wildfire. Its nest was totally destroyed, but the little eagle had fallen to the ground and survived. After the fire, he was found by Kent Keller, a volunteer for Utah’s Div. of Natural Resources, who had banded the young eagle a month before. The eagle was dehydrated—his feathers, face, and feet were badly burned. So Keller obtained a permit from wildlife officials to intervene. Now in the care of the Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Northern Utah the eagle is recovering rapidly. Even so, it will take a while for the damaged feathers to be replaced by healthy new ones. Phoenix–as is he was aptly named–won’t learn to fly for at least another year.

With this and other fire-related stories in the news, I‘ve been wondering about the fate of animals caught in wildfires. Scientific observations of animal behavior during fire events are rare. But by conducting post-fire surveys, and comparing results with unburned areas, some researchers have been able to piece together an idea of who survives, who dies and who thrives.

Obviously, faster and more mobile animals have the advantage. Birds can fly away and most mammals can outrun the spreading flames. Spring fires can be disastrous, destroying birds who haven’t fledged –like Phoenix– or mammals who are still too immature to escape. Fortunately, fires are more frequent in mid to late summer when little ones have matured.

If a fire moves through an area quickly, without superheating the ground, dormant animals or those hiding in burrows can survive. The surrounding soil provides plenty of insulation. Soil also protects most soil macrofauna and the pupae of many insects.

Animals that live their lives totally or partially in the water may not suffer at all during a fire. However, smaller bodies of water, such as streams, can quickly heat up fairly quickly. Oxygen loss is a problem as well. And fire-fighting chemicals dumped from the air can end up in water, killing fish, frogs and other animals.

Indirectly, the alteration of habitat by fire can also restructure animal populations. Interestingly, there are quite a lot of animals that benefit from post-fire habitats. For example, the insect population above ground may plummet during a fire, but then increase above pre-fire levels when fresh young plants start to grow back. Burned trees are attractive to certain beetles as breeding sites. An increase in beetles is a windfall for the woodpeckers that devour them. Swallows and flycatchers use burned dead trees as perch sites. They survey from on high and then swoop to catch their insect dinner. Seed eating birds like Clark’s Nutcracker, gobble up conifer seeds when cones open in response to fire.

Among mammals, ground squirrels, pocket gophers and deer mice generally increase after severe fires. Even large herbivores such as pronghorn or deer may benefit from the increased food and nutrition on recent burns. In turn, predators of these creatures enjoy a bumper crop as well.

For images of Phoenix the recovering golden eagle and a link to the Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Northern Utah go to www.wildaboututah.org.

For Wild About Utah, I’m Holly Strand.

Credits:

Images: Courtesy Wikimedia, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, Gavin Keefe Schaefer and Dave Menke, US FWS images.fws.gov

Text: Holly Strand

Sources & Additional Reading:

Baker, William L. 2009. Fire ecology in Rocky Mountain Landscapes. Washington, DC: Island Press.https://islandpress.org/ip/books/book/islandpress/F/bo7019409.html

Bradley, Anne F.; Noste, Nonan V.; Fischer, William C. 1992. Fire ecology of forests and woodlands in Utah. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-287. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station. https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs_int/int_gtr287.pdf

Hutto, RL. 1995. Composition of bird communities following stand-replacement fires in northern Rocky-Mountain (USA) conifer forests in Conservation Biology Volume: 9 Issue: 5 Pages: 1041-1058 https://www.fsl.orst.edu/ltep/Biscuit/Biscuit_files/Refs/Hulto%20CB1995%20fire%20birds.pdf

Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Northern Utah https://wrcnu.org/