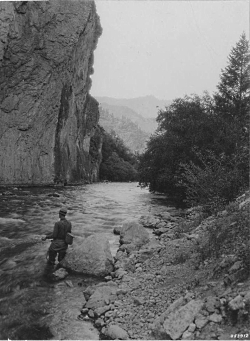

Courtesy & Copyright Josh Boling, Photographer

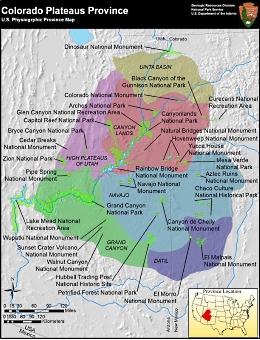

Walking north out of Logan, I’ll wander through the grid-patterned neighborhoods that pepper the flanks of the Bear River Range, the still-snowy peaks that serve as sentinels over my daily commute and the adventure on which I embark now. They serve another, greater purpose, too, though. Without the Bear Rivers, the Rocky Mountains would be otherwise dissected. The snowy peaks I adore and which now pass in slow motion over my right shoulder form the only range of mountains that connect the northern and southern Rockies. Though they only measure about 70 miles in length, they provide a critical ecological thoroughfare from the south end of Cache Valley, Utah, north to Soda Springs, Idaho.

I won’t follow them that far, though. I’ll turn left (west) at the Idaho border toward the Great Basin.

I’m technically already there. We all are if we live along the Wasatch Front. And there are just a few minor ranges—the Clarkston Range, Blue Spring Hills, and the northern fingerling ridges of the Promontory Mountains—to wander across before reaching the Great Basin proper.

My favorite hidden gem of this often-overlooked portion of Utah are the Raft River Mountains. Like the mighty Uintas to the east, the Raft Rivers run East-to-West. So, despite being a stone’s throw from the Great Salt Lake, the tributaries running off their northern flanks drain not into the Great Basin and the Great Salt Lake, but north onto the Snake River Plain toward the Columbia River and, eventually, the Pacific Ocean.

The Tri Corners Landmark is a simple granite pillar sticking 3 or 4 feet out of the sand amongst wind-whipped sage brush. It’s easy to miss, but marks some interesting irregularities. Utah’s political border is not, in fact, made up of straight lines. According to cartographer Dave Cook, surveyors who created the state’s initial boundaries hastily covered ground with their crude survey instruments. They were paid by the mile, so they were more interested in finishing quickly than correcting any errors they made along the way.

The border wiggles at least four times by my calculations—one of which comprises two right angles—as it wanders across ridgelines and through the dusty draws of the basin and range mountains toward the Mojave Desert of southwest Utah.

Courtesy & Copyright Josh Boling, Photographer

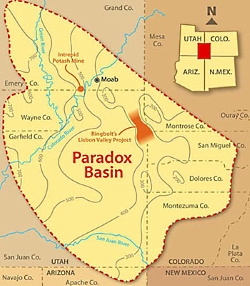

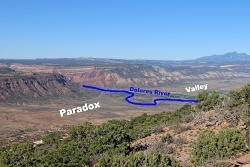

The eastern border we share with Colorado is a varied expanse of high desert plateaus, rugged cliffs, out-of-place riparian zones, and a few spectacular snow-capped mountain ranges leading through some of the most beautiful and gloriously desolate places on the planet. The Book Cliffs, Dinosaur National Monument, and the La Sal Mountains come to mind.

A short walk distance-wise would require heaps of route finding across the Green River’s Flaming Gorge and along the northern toes of the Uinta Mountains. Here is perhaps the greatest of Utah’s geologic juxtapositions. Low basins adjacent the Intermountain West’s highest peaks.

Perhaps you’re inspired now to know parts of this walk better yourself.

I’m Josh Boling, and I’m Wild About Utah!

Credits:

Imaginary Wanderings:

Photos: Courtesy and Copyright Josh Boling, Photographer

Audio: Includes audio from

Text: Josh Boling, 2020, Edith Bowen Laboratory School, Utah State University

Sources & Additional Reading

Boling, Josh, Why I Teach Outside, Wild About Utah, November 11, 2019, https://wildaboututah.org/why-i-teach-outside/

Kiffel-Alcheh, Utah, National Geographic Kids, https://kids.nationalgeographic.com/explore/states/utah/

The Geography of Utah, NSTATE LLC, https://www.netstate.com/states/geography/ut_geography.htm

Fisher, Albert L, Physical Geography of Utah, History to Go, Utah Division of State History, https://historytogo.utah.gov/physical-geography-utah/