Courtesy Wikimedia, Brett Neilson, Photographer

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

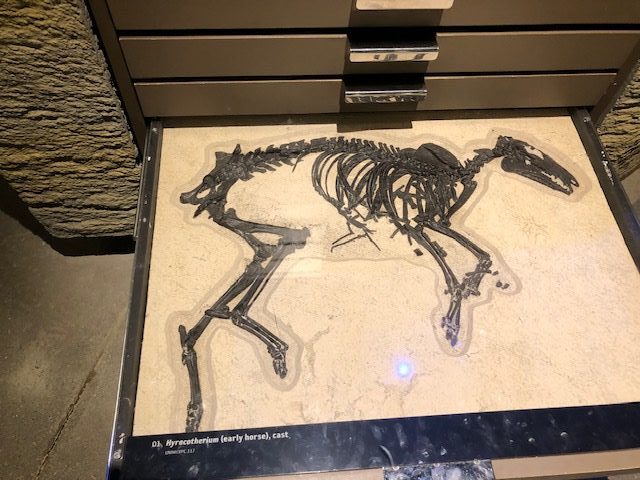

The special ice age exhibit has left Salt Lake, but a visit to the Museum of Natural History is always a treat. Its skeleton of a mammoth clearly conveys a feeling for its massive size. Also looking huge is their skeleton of a giant sloth, standing 8 feet high and sporting a hand claw over 12 inches long. Back when Thomas Jefferson was president of the United States, some explorers found a similar claw in a cave in Virginia and sent it to him.. Jefferson quickly sent off an urgent message to Lewis and Clark on their trek west to keep an eye out for this fiercesome beast. As it turns out, the giant sloth was extinct and had just been a vegetarian who lived mostly in the trees. The giant sloth used the claw to pull tree branches closer so he could eat the leaves.

If you walk down the museum ramp leading away from the giant sloth, you leave the Ice Age and go deeper back in time to the Age of Dinosaurs. You pass by a prehistoric crocodile and a giant birdlike creature standing on large, three toed claw feet. This bird would run down its prey at speeds as high as 30 mph. Soon you arrive at a section of glass flooring, exposing a massive jumble of bones underfoot. You have arrived at the exhibit on Utah’s unique Cleveland-Lloyd quarry. In the early 1900’s, some cowboys and sheepherders noticed some large bones sticking out of a hillside about 30 miles away from the current town of Price. The scientific community was alerted, and digging at the site began. To this day, over 10,000 bones have been unearthed, and the majority identified as belonging to predator dinosaurs. But we still don’t know how or why this massive bone yard was created.

Four paleontologists have stepped forward and offered their best guess as to why so many dinosaur bones are here. One by one these four men appear on video screens along the museum path. The first one says this was once a watering hole. The dinosaurs came to drink, but the watering hole dried up. The dinosaurs died of thirst.

Oh no, said the second. There was actually too much water. The mud surrounding the watering hole became so deep the dinosaurs got stuck in the mud.

The third agreed that the dinosaurs came to the site to drink. But somehow the water had become contaminated. The dinosaurs drank and died of poison.

The fourth simply said the dinosaurs had died somewhere else, and the bones had been washed down to this site.

It’s still a mystery waiting to be solved.

In the meantime, the work of discovery goes on. Fossils are being found, and the promising ones are wrapped in plaster casts and sent to the lab. You can look in the lab windows as you exit the museum. A crew of staff and volunteers in white lab coats are picking up small hammers, picks and dentist drills. Slowly, carefully, they are cutting back the layers of time.

The answer to the question about the origin of Utah’s dinosaur bone yard seems to still lie just around the corner.

This is Mary Heers and I’m Wild About Utah

Credits:

Photos: Courtesy Wikimedia and US Bureau of Land Management

Featured Audio: Courtesy & Copyright © Anderson, Howe, and Wakeman Utah Public Radio upr.org

Text: Mary Heers, https://cca.usu.edu/files/awards/art-and-mary-heers-citation.pdf

Additional Reading: Lyle Bingham, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading

Wild About Utah, Mary Heers’ Wild About Utah Postings

Natural History Museum of Utah, University of Utah, http://nhmu.utah.edu

301 Wakara Way, Salt Lake City, UT 84108

Cleveland Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, US Bureau of Land Management (BLM), US Department of the Interior, https://www.blm.gov/visit/cleveland-lloyd-dinosaur-quarry

Cleveland Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, Jurassic National Monument, US Bureau of Land Management (BLM), US Department of the Interior, https://www.blm.gov/programs/national-conservation-lands/utah/jurassic-national-monument/photos

Cleveland Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry: Paleontological Resource Management, https://yout-ube.com/watch?v=YotsxDLDMSE

Cleveland Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry: The Interpretive Center, US Bureau of Land Management (BLM), US Department of the Interior, https://yout-ube.com/watch?v=YotsxDLDMSE