Whether you live in a desert, a city, a suburb or a farm, your life would change if you lived in a world without trees. You may be a person who appreciates their ecological connections, or have complete disregard for them. As William Blake said, “The tree, which moves some to tears of joy, is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way.1”

So, take a moment and consider the way the world would look, and function, without trees. Currently, forests cover about 30% of the Earth’s land surface. But that’s a loss of 1/3 of all trees just since the beginning of the industrial era. The top five largest forests are located in Russia, Brazil, Canada, the U.S., and China.

Whether you think climate change is natural or human-caused, it affects forests by altering the intensity of fires, creating windstorms, changing precipitation, and enabling introduced species to invade. And the World Resources Institute estimates that tens of thousands of forested acres are destroyed every day.

Sometimes even fragmenting forests can produce harmful results as die-backs occur along the edges, and certain wildlife species will not breed unless they live in large tracts of forested areas. It has been said that roads, which are a cause of fragmentation, are the pathways to forest destruction.

Most people know that trees take in Carbon Dioxide for growth, and release Oxygen via photosynthesis. But trees also remove many air pollutants, provide cooling shade and protection from wind and the sun’s harmful Utra-Violet rays. They can be used as privacy screens, they prevent soil erosion, and are the foundation of wildlife habitat on land. Some provide food, can provide serenity and solitude, and have been proven to reduce stress levels. Their fallen leaves decompose into valuable soil. They reduce the Heat-Island Effect in cities, and are more resistant to climate change impacts. Research has shown they improve retail shopping areas, and speed recovery time for those in health care centers.

For the budget-conscious folks, a mature tree can raise home-property values by as much as $5000. And think about those beautiful Autumn colors.

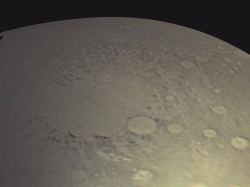

Courtesy NASA/JPL Caltech

Composed from images taken by the Mars Color Imager (MARCI) camera on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

Perhaps a re-evaluation of trees is warranted. Ponder these imaginative thoughts penned by well-known writers:

Ralph Waldo Emerson: At the gates of the forest, the surprised man of the world is forced to leave his city estimates of great and small, wise and foolish. The knapsack of custom falls off his back.

William Henry Hudson: When one turned from the lawns and gardens into the wood it was like passing from the open sunlit air to the twilight and still atmosphere of a cathedral interior.

Stephanie June Sorrrell: Let me stand in the heart of a beech tree, with great boughs all sinewed and whorled about me. And, just for a moment, catch a glimpse of primeval time that breathes forgotten within this busy hurrying world.

One way for us to resolve tree issues, is to plant them. And the best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago. But the next best time to plant them is today.

“Silence alone is worthy to be heard.” – Henry David Thoreau

This is Ron Hellstern, and I am Wild About Utah.

Credits:

Images: CourtesyCourtesy NASA/JPL Caltech

Audio: Contains audio courtesy and copyright Friend Feller, Utah Public Radio, UPR.org

Text: Ron Hellstern, Cache Valley Wildlife Association

Additional Reading

Upton, John, Could Common Earthly Organisms Thrive on Mars?, Pacific Standard, May 21, 2014, https://psmag.com/environment/mars-81952

Voak, Hannah, A World Without Trees, Science in School, https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Marriage_of_Heaven_and_Hell.html?id=YUa8AQAAQBAJ

Hudson, William Henry, The Book of a Naturalist, p4, https://books.google.com/books?id=NA4KAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA4&lpg#v=onepage&q&f=false