Platypedia putnami

Elko Co., Nevada

June 2008

Courtesy & Copyright 2008

Jim Cane, Photographer

Cast Nymphal Skin of the

Cast Nymphal Skin of the

Crepitating Cicada

Platypedia putnami

Elko Co., Nevada

June 2008

Courtesy & Copyright 2008

Jim Cane, Photographer

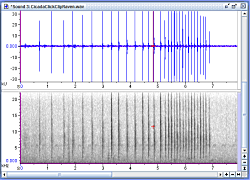

Audiospectrograph of the

Audiospectrograph of the

Crepitating Cicada

Platypedia putnami

Made with Raven Software

Elko Co., Nevada

June 2008

Courtesy

Jim Cane, creator

East Coast news reports have been abuzz about this summer’s synchronized emergence of the periodic cicada, last seen in 1996 when their parental generation flew. The incessant loud buzzing of these 17 year cicadas has been the dominant sound of mid-Atlantic forests and towns for some weeks now.

The Great Basin also has cicadas. Our two species from the genus Platypedia produce a more subdued mating call. They use crepitation, from the Latin for a crackling sound. Our crepitating cicadas have received scant research attention; even their means of sound production remains uncertain. Their call consists of a trill of accelerating clicks.

You can see an audio spectrograph of their clicking call on our Wild About Utah website. The wings of crepitating cicadas visibly clap to the tempo, leading some to believe that the sound is that of slapping wings. More likely, the snapping sound is generated by the bending of a wing vein or other semi-rigid surface in the manner of a metal dog training clicker. Listen to the similarity.

As with cicadas everywhere, our crepitating cicadas spend years underground as slow growing, wingless immatures called nymphs. Cicada nymphs feed in a manner similar to their smaller kin the aphids, white flies and scales, piercing the roots of trees and shrubs to suck their sweet sap. When and where adult cicadas are abundant, you can see scattered cast brittle skins from which the adults emerged. Tunneling by cicada nymphs has been shown to alter the morphology of Great Basin soils, but it is their collective daytime clicking that grabs your attention.

En masse, they sound like an orchestra of castanets. At sunset, as if on cue, they all become quiet for the night. After hearing our crepitating cicadas clicking all day long, that evening silence is profound.

Credits:

Images: Courtesy & Copyright 2008 Jim Cane, Photographer

Recording: Courtesy & Copyright Jim Cane

recorded with Raven software: Bioacoustics Research Program. (2011). Raven Pro: Interactive Sound Analysis Software (Version 1.4) [Computer software]. Ithaca, NY: The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Available from https://www.birds.cornell.edu/raven.

Sound clip of the call of the 17-year periodic cicada, Courtesy Dan Mozgai, from his website, https://www.cicadamania.com/. Copyright Dan Mozgai.

Clicking sound of the crepitating cicada, Platypedia putnami. Logan Utah, June 2013. Copyright Jim Cane

Text: Jim Cane, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading:

Cicada Mania, https://www.cicadamania.com/