by Alfred Ralph Robbins

Courtesy & © Shannon Rhodes, Photographer

Oft have we, my friends and I,

Left cares of home, and work day woes

To find a haven, there cast a fly;

And where we’ll camp–God only knows.

Oft have we hiked the trail uphill

To see it pass, and again return–

Walked mile on mile, to get the thrill

Of a meadow lake and a creel filled.

Oft round the lake we’ve cast and fussed

And wished it something we might shun;

But something deep inside of us

Just holds us fast till day is done.

Courtesy & © Shannon Rhodes, Photographer

Courtesy & © Shannon Rhodes, Photographer

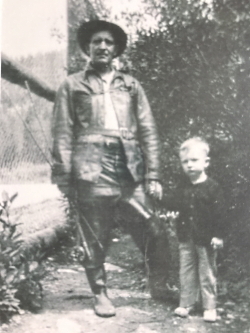

Do you have similar memories in the wild with your grandparents recorded somehow? Turning to one of my favorite books, “Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place,” I read again how Terry Tempest Williams described the memories with her grandmother among avocets, ibises, and western grebes during their outings in Utah’s Great Salt Lake wetlands. Grandmother Mimi shared her birding fascination with her granddaughter Terry along the burrowing owl mounds of the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge. Williams wrote, “It was in 1960, the same year she gave me my Peterson’s Field Guide to Western Birds. I know this because I dated their picture. We have come back every year since to pay our respects.”

I’m not a grandmother yet, but I will one day make a trek over Hades Pass again, gaze at the Grandaddy Basin below, and capture nature’s poetry with pen, camera lens, and little hiker hands in mine. Bloggers have technologies today to share instantly with me and the rest of the world their adventures in this Grandaddy Wilderness region. Documenting autobiographical history has evolved from dusty diaries and scrapbooks with black-and-white photographs to today’s digital image- and video-filled blogs in exciting ways that can include the places in Utah you love with the generations you love. Consider it your contribution to history.

by Alfred Ralph Robbins

Courtesy & © Shannon Rhodes, Photographer

I would not miss the Oh’s! and Ah’s!

I’ve seen in Doug’s and Noel’s eyes,

When first they saw Grandaddy Lake

From the summit, in the skies.

They are thrilled I know, and so am I.

They show it in their face;

While I just swallow hard and try

To thank God for this place.

I am Grandaddy Basin poet Alfred Ralph Robbins’s great granddaughter Shannon Rhodes, and I’m wild about Utah.

Credits:

Images: Courtesy & Copyright Shannon Rhodes, Photographer

Audio: Courtesy & © Kevin Colver https://wildstore.wildsanctuary.com/

Text: Shannon Rhodes, Edith Bowen Laboratory School, Utah State University https://edithbowen.usu.edu/

Additional Reading Links: Shannon Rhodes

Additional Reading:

Williams, Terry Tempest. 1992. Refuge: an unnatural history of family and place. New York: Vintage Books. https://www.amazon.com/Refuge-Unnatural-History-Family-Place/dp/0679740244

Andersen, Cordell M. The Grandaddies. 2015. https://cordellmandersen.blogspot.com/2015/06/photoessay-backpack-1-2015-grandaddy.html

Wasatch Will. Fern Lake: Chasing Friends in Grandaddy Basin. 2018. https://www.wasatchwill.com/2018/06/fern-lake.html

Delay, Megan and Ali Spackman. Hanging with Sean’s Elk Party in the Uinta’s Grandaddy Basin. 2015. https://whereintheworldaremeganandali.wordpress.com/2015/09/05/hanging-with-seans-elk-party-in-the-uintas-grandaddy-basin/

Rhodes, Shannon, Wild About Nature Journaling, Wild About Utah June 22, 2020, https://wildaboututah.org/wild-about-nature-journaling/