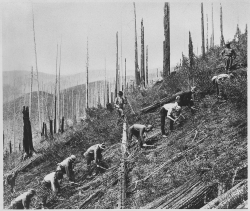

Civilian Conservation Corps

enrollees clearing the land

for soil conservation

Photo Courtesy National Archive

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library (NLFDR)

Terraces near Mount Nebo trailhead

Payson Canyon

Photo Courtesy & Copyright © 2011

Lyle W. Bingham, Photographer

Albert Potter

Photo Courtesy USDA Forest Service

The Greatest Good

A Forest Service Centennial Film

Hi, this is Mark Larese-Casanova from the Utah Master Naturalist Program at Utah State University Extension.

The History

of our

National Forests

Warm springtime weather brings clear trails up in the mountains, and hiking through the shade of Douglas-fir on a warm weekend day had me wondering about Utah’s National Forests and how they came to be.

Back in the days of the early pioneers, Utah’s mountains were recognized as resources for survival, providing clean water for drinking and irrigation and lumber for building homes. The high mountain pastures were also valuable summer forage for livestock. In the late 1840’s, Parley Pratt declared, “The supply of pasture for grazing animals is without limit in every direction. Millions of people could live in these countries and raise cattle and sheep to any amount.” Many settlers shared this view, and unmanaged grazing resulted in deteriorated rangelands in just 20 to 30 years. By 1860, some Utah towns were experiencing regular flooding and heavy erosion due to insufficient vegetation to stabilize the soil. Unregulated wholesale timber harvesting during the same period also contributed to these conditions.

In 1881, the US Department of Agriculture’s Division of Forestry (later renamed the Forest Service) was established, and its first job was to gather information about the condition of the nation’s forests. In 1902, Albert F. Potter, who was the inspector of grazing for the General Land Office, conducted a survey of potential Forest Reserves in Utah. Potter stated that “the ranges of the State have suffered from a serious drought for several years past, and this, in addition to the very large number of livestock, especially of sheep, has caused the summer range to be left in a very barren…condition.”

The demand for lumber and wool during the First World War again led to increased timber harvesting and grazing on our forests. During the Great Depression of the 1930’s, Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to help implement conservation projects across the country. The CCC was fundamental in re-foresting much of the Wasatch and Uinta Mountain ranges, planting over three million trees in nine years.

Utah’s Forest Reserves were created in the years soon after Albert Potter’s surveys, and were gradually combined into Utah’s seven National Forests that now cover approximately 10,500,000 acres, or about 20%, of the state. Grazing and timber harvesting still occur on much of Utah’s National Forests, but our practices are supported by scientific research and over a century of experience, ensuring more sustainable multiple use and management of our forests today.

For Wild About Utah, I’m Mark Larese-Casanova.

Credits:

Images: Courtesy National Archives, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library

and Courtesy and Copyright © 2011 Lyle W. Bingham

Text: Mark Larese-Casanova, Utah Master Naturalist Program at Utah State University Extension.

Additional Reading:

Baldridge, K.W. The Civilian Conservation Corps in Utah. Utah History To Go.

https://historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/from_war_to_war/thecivilianconservationcorps.html

Prevedel, D.A., and C.M. Johnson. 2005. Beginnings of Range Management: Albert F. Potter, First Chief of Grazing, U.S. Forest Service, and a Photographic Comparison of his 1902 Forest Reserve Survey in Utah with Conditions 100 Years Later. United States Department of Agriculture, US Forest Service. R4-VM 2005-01. https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs_other/r4_vm20005_01.pdf

CCC Camps in Utah, CCClegacy.org https://www.ccclegacy.org/CCC_Camps_Utah.html