Photo Courtesy Sevier County

Kreig Rasmussen, Photographer

Hi, I’m Ru Mahoney with Stokes Nature Center in Logan Canyon.

Utah’s culture is rich with vestiges of our pioneer history, and the landscape is accented by visible signs of the European settlers who forged our modern communities. But the tapestry of Utah’s cultural heritage is interwoven with much older threads, as indelible and enduring as the landscape itself.

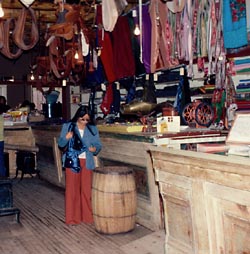

In the 1980’s, in the southwestern quadrant of central Utah, the construction of interstate 70 unearthed a secret over one thousand years old. The valleys and canyons of what is now Sevier County, already known as a seasonal thoroughfare for the Paiute, had an even older history as home to the largest community of Fremont Indians ever discovered. Influenced by their Anasazi cousins to the southwest, the Fremont culture encompassed a diverse group of tribes that inhabited the western Colorado Plateau and the Great Basin area from roughly 400 to 1350 A.D. Archaeologists tell us they were a people of ingenuity in their engineering, aggression in their social interactions, and lasting creativity in their artistic expression. Divergent theories on their fate suggest they drove the Anasazi out of the Four Corners region and eventually migrated to further landscapes, or that northern groups of Fremont peoples joined with bands of Shoshone and became the Ute Indians of the Uinta. Whatever the truth of their ultimate fate may be, nowhere is their history more tangible than at Fremont Indian State Park just south of Sevier, UT along I-70. This year-round state park offers visitors a treasure trove of artifacts and curated exhibits in an excellent visitor’s center. But the most authentic interaction with these past peoples comes from exploring the surrounding landscape.

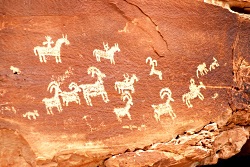

Driving the winding road into Clear Creek Canyon, ghostly figures begin to emerge; pictographs painted in shades of ocher and umber, and pale petroglyphs carved into the canyon walls, reveal an archaic and epic account of Utah’s ancestral past. A unique creation story, in which a shrike leads the Fremont people from a dark and cold underworld through the stem of reed into the warm world above, plays out across the canyon walls. A craggy outcrop of rock in the shape of an eagle is said to be watching over the reed to the underworld below to insure nothing wicked escapes into our world. A concentric lunar calendar and an abundance of zoomorphics speak of a cultural identity conceived in relation to the broader astrological world, and a reverence for anthropomorphized neighbors such as bighorn sheep and elk. Spider Woman Rock juxtaposes a powerful figure of Native American mythology with the pedestrian humility of a nursing mother. And Cave of 100 Hands is a visceral exhibition of a humanity simultaneously reminiscent and divergent from our own.

While the Fremont culture is believed to have died out or been absorbed by other modern groups, Clear Creek Canyon and the rock art sites of Fremont Indian State Park are significant among the modern Kanosh and Koosharem Bands of the Paiute who began using the area and leaving their own indelible marks on the canyon walls after the disappearance of the Fremont peoples around 1400 A.D. On the vernal and autumnal equinox (occurring in the third or fourth week of March and September each year) the eagle rock casts its shadow over the reed rock at dawn, breathing life into ancient tales of our ancestral history.

Fremont Indian State Park is a notable destination for those interested in rock art sites, many of which are suited to families of all ages and mobility, including visitors with strollers and wheelchairs. Stop in the visitor’s center to borrow or purchase a guide to the petroglyphs and pictographs for deeper insight into the Fremont culture and an unforgettable glimpse into Utah’s past.

For Wild About Utah and Stokes Nature Center, I’m Ru Mahoney.

Credits:

Images: Courtesy Sevier County, Kreig Rasmussen, Photographer

Text: Ru Mahoney, Stokes Nature Center in Logan Canyon.

Additional Reading:

https://stateparks.utah.gov/parks/fremont-indian/

https://www.nps.gov/grba/learn/historyculture/fremont-indians.htm

https://www.thefurtrapper.com/fremont_indians.htm

Take the Pledge to Protect the Past, Utah State Historical Preservation Office, Department of Cultural & Community Engagement, State of Utah, https://ushpo.utah.gov/shpo/upan/