Courtesy and © Andrea Liberatore

Surface tension – water drops

Surface tension – water drops

on a quarter

Courtesy and © Andrea Liberatore

In our winter wonderland, water is all around. It piles upon the landscape in great white drifts. It is a substance life is completely dependent upon and as ordinary as it seems, this tasteless, odorless substance is actually quite amazing. Up to 60% of our body mass is due to water, and life as we know it would not exist if not for water’s unique physical properties.

Properties of Water

When most known liquids get colder they contract – shrinking around 10 percent in total volume. Water contracts too, but only until it reaches its freezing point, at which time it reverses course and begins to expand. This molecular marvel does wonderful things for life on earth. As water freezes and expands, the resulting ice becomes lighter than its liquid form, causing it to float. If ice contracted as other liquids do, it would sink, and lakes would freeze from the bottom up – and freeze quickly, meaning big changes for aquatic life. Water in all forms happens to be a very good insulator, meaning that it doesn’t change temperature very quickly. Ice floating on top of a pond insulates the water underneath, keeping it warmer, and therefore liquid, longer than it normally would. Obviously, this is beneficial for local creatures like fish and beavers not to mention the penguins, whales and seals that thrive in the colder parts of our planet.

Another critical property of water is its stickiness. Individual molecules are generally more attracted to each other than to other substances such as air or soil. This ‘stickiness’, or cohesion, creates surface tension, which allow puddles, rivers, and raindrops to form, and also enables water striders to glide on the water’s surface and rocks to skip across a lake. Water tension is also responsible for a tree’s ability to siphon water from the soil and transport it to the very topmost leaf. However, water’s bonds aren’t so strong as to be unable to break when a fish swims through or when you cannonball into the deep end. You can observe surface tension at home by dripping water onto the head of a coin, and watching it ball up into a surprisingly large mound.

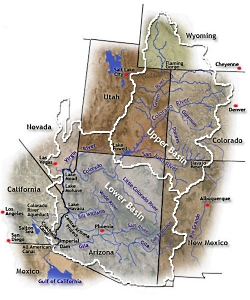

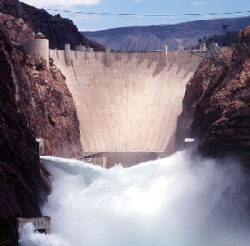

Water is also one of the only known substances that naturally occurs in three phases – solid, liquid, and gas. This is important to many facets of life including the proper functioning of the weather system as we know it. Thankfully, there is a lot of water here on earth – about 320 million cubic miles of it. However, only four tenths of a percent of that comes in the form of freshwater lakes & rivers. Most of the rest is locked up in glaciers and oceans. It’s also important to realize that this is all of the water that Earth has ever had, and all the water we’re ever going to get, which can lead to some interesting thoughts about where that water you are about to drink has previously been. Perhaps it was once part of Lake Bonneville, in the snow that fell on the back of a wooly mammoth, or in a puddle slurped up by a brachiosaurus. If only water could talk…

For more sources and to calculate your water-use footprint, visit our website at www.wildaboututah.org.

For the Stokes Nature Center and Wild About Utah, this is Andrea Liberatore.

Credits:

Images: Andrea Liberatore, Stokes Nature Center in Logan Canyon.

Text: Andrea Liberatore, Stokes Nature Center in Logan Canyon.

Additional Reading:

Bryson, Bill (2004) A Short History of Nearly Everything. Broadway (Random House): New York.

U.S. Geological Survey (2013) The USGS Water Science School. Accessible online at: https://ga.water.usgs.gov/edu/

United Nations: Water. Accessible online at https://www.unwater.org/

Calculate your water footprint:

https://www.waterfootprint.org/?page=files/YourWaterFootprint