James M. Robb Colorado River State Park

Fruita, CO

Courtesy Daniel Smith, Photographer

The Colorado River from

The Colorado River from

Dead Horse Point State Park,

near Moab,Utah, USA

Courtesy Phil Armitage, Photographer

Confluence of the Colorado and Green Rivers

Confluence of the Colorado and Green Rivers

in Canyonlands National Park

Courtesy USGS

Photo by Marli Miller, Photographer

Confluence of the Colorado and Green Rivers

Confluence of the Colorado and Green Rivers

in Canyonlands National Park

Courtesy National Park Service

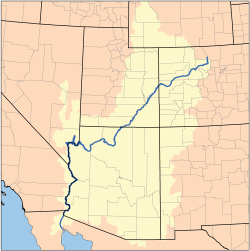

Map of the Colorado River Watershed

Map of the Colorado River Watershed

by Karl Musser based on USGS data

This file is licensed under the

CCA ShareAlike 2.5 License.

Hi, I’m Holly Strand of Stokes Nature Center in beautiful Logan Canyon.

The Colorado River is the largest waterway in the southwest. 1,450 miles long, the Colorado River basin drains 248,000 square miles in 7 large states. In Utah, the river enters near Cisco south of I-70, winds its way through Arches and Canyonlands National Parks, then flows through Glen Canyon and exits south into Arizona.

Less than 100 years ago, the Colorado River wasn’t in Utah or even in Colorado. Until 1920, “Colorado River” referred only to the river section downstream from Glen and Grand Canyons. Upstream, it was called the Grand River all the way up the headwaters in the Colorado Rockies. Thus we have Grand County in Utah and the town of Grand Junction in Colorado.

According to Jack Schmidt, professor in Utah State University’s Department of Watershed Sciences and a longtime scholar of the river, the good citizens of the state of Colorado weren’t pleased with the Colorado River’s location.

So in 1920, the Colorado Legislature renamed Colorado’s portion of the Grand River, with a somewhat awkward result: The Colorado River began in Colorado, became the Grand River at the border with Utah and then became the Colorado River again at the confluence with the Green.

This arrangement did not last long –again because of a Colorado legislator. U.S. Representative Edward T. Taylor, petitioned the Congressional Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce to rename the entire river as the Colorado. Despite objections from Utah and Wyoming representatives and the U.S. Geological Survey, the name change was made official by the U.S. Congress on July 25, 1921.

The objections were legitimate: In the 1890s the Federal Board on Geographic Names established the policy of naming rivers after their longest tributary. The former Grand River of Colorado and Utah was shorter than the Green River tributary by quite a bit. So the Green river should have prevailed and the Colorado should have been one of its tributaries.

However, if you judge tributary primacy by volume, the Colorado wins hands down. 100 years ago, the upper Colorado (or former Grand River) had a significantly higher total flow than the Green.

But what’s in a name? Prior to widespread European settlement, the Grand River was known as Rio Rafael and before that, different parts of the river had numerous Native American and Spanish names. A thousand years from now the rapidly evolving Colorado could have an entirely different identity. The main thing is that Utahns can enjoy and appreciate the habitat, scenery and many resources that this important waterway provides.

Thanks to the USU College of Natural Resources and the Rocky Mountain Power Foundation for supporting research and development of this Wild About Utah topic.

For Wild About Utah and Stokes Nature Center, I’m Holly Strand.

Credits:

Images:

JamesMRobbColorado_riverDanielSmith.jpg: Taken in the Island Acres Part of James M. Robb Colorado River State park by Daniel Smith and released into the Public domain.

DeadHorsePtSP_UtahPhilArmitage.jpg: The Colorado River from Dead Horse Point State Park, near Moab, Utah, USA. Photo by Phil Armitage (May be used for any purpose)

ConfluenceUSGSMarliMiller.jpg: Confluence of the Colorado and Green Rivers in Canyonlands National Park. USGS Photo by Marli Miller.

ConfluenceNPS.jpg: Confluence of the Colorado and Green Rivers in Canyonlands National Park. National Park Service.

Colorado River Watershed Map, by Karl Musser based on USGS data, licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 2.5 License: In short: you are free to share and make derivative works of the file under the conditions that you appropriately attribute it, and that you distribute it only under a license identical to this one. Official license

Text: Mary-Ann Muffoletto, Holly Strand, Content reviewed by Jack Schmidt of Utah State University’s Department of Watershed Sciences and a longtime scholar of the Colorado River.

Sources & Additional Reading:

Benke, A. C., and C. E. Cushing (editors). 2005. Rivers of North America. Academic/Elsevier. Amsterdam/Boston, 1168 pages.

Casey, Robert L. Journey to the High Southwest. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot, 2007, p. 20.

Colorado Historical Society, Frontier Historical Society, www.bioguide.congress.gov

https://www.postindependent.com/article/20080325/VALLEYNEWS/68312863

”First Biennial Report of the Utah Conservation Commission, 1913,” Salt Lake City, Utah: The Arrow Press Tribune-Reporter Printing Co., 1913. p. 131.

McKinnon, Shaun. “River’s headwaters determined by politicians, not geography.” The Arizona Republic, 25 July 2004.

James, Ian, Scientists have long warned of a Colorado River crisis, The Los Angeles Times, July 15, 2022, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-07-15/scientists-have-long-warned-of-a-colorado-river-crisis

Big Sagebrush

Big Sagebrush Shadscale Saltbush

Shadscale Saltbush