Flickers Tapping Love Codes on my Roof

Courtesy & © 2007 Buck Russell

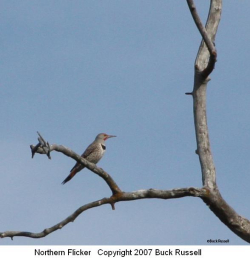

Have you ever woken up to this sound [Flicker pounding on a roof] and wondered what in the world was going on? This is the sound of the Northern Flicker, a large, ant-eating woodpecker found in open woodlands, savannas, and forest edges throughout North America.

The western subspecies, the Red-shafted Flicker, can be found year round in Utah. Its largish brown body with spotted breast, and thin dark bars across its back are unmistakable. Both sexes have a black collar and a red spot on the head—males on the back of the head and females on the side.

Breeding season is when you’d be most likely to hear the flicker drumming loudly on your house or nearby trees. Flickers—like other woodpeckers–drum to attract mates and defend territory—they are not looking for food. Both sexes drum and you’ll usually hear the drumming in conjunction with their Long Call, [ play long call]

Flicker drumming is produced by rapidly and sharply beating the tip of the bill on some sort of resonating object, usually a dead tree, limb or branch, sometimes a metal surface. They will use aluminum siding, as well as the trim and fascia boards of wood, brick, and stucco homes. They’ll also go for metal downspouts, gutters, chimneys, and vents.

Scientists have measured just over one second as the average duration of drum roll, with averages of 22 to 25 total beats in drum roll.

Does it hurt the little fellow to bang his head repeatedly across a hard surface? No. Flickers and other woodpeckers have thickened skulls and powerful neck muscles that enable them to deliver sharp blows without damaging their internal organs. A spongy, elastic tissue connects these flexible joints between the beak and the skull acting as a shock absorber. Bristly feathers around the nostrils help filter out the wood dust created as the flicker pounds away.

Luckily for homeowners, holes made by drumming activities are usually just small, shallow dents in the wood. And the drumming usually stops once breeding begins in the spring. For the most part, flickers spend their time digging in the ground slurping ants with their long tongues. If a flicker really starts to get on your nerves—there are some things you can do to discourage his behavior–like hanging Mylar reflective tape or streamers to the area where he likes to drum. Personally, the sound doesn’t bother me once I know the source is an attractive bird whose taste in real estate just happens to be the same as mine.

Credits:

Audio: American Flicker sound courtesy Xeno-Canto.org, recorded by Ryan O’Donnell.

Formerly: American Flicker sound for this recording used by permission of the copyright holder Kevin Colver and found in the Western Soundscape Archive at the University of Utah J. Willard Marriott Library. https://westernsoundscape.org/ Dr. Colver’s Soundscape albums are also available for download from WildSanctuary.com.

Photo: Used by Permission of the photographer Buck Russell, Bridgerland Audubon Member

Text: Bridgerland Audubon Society: Lyle Bingham, Bridgerland Audubon Society, Holly Strand Stokes Nature Center

Voice: Richard (Dick) Hurren, Bridgerland Audubon Society

Additional Reading

Northern Flicker, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Northern_Flicker/

Northern Flicker, Utah Species, Utah Conservation Data Center, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, State of Utah, https://dwrcdc.nr.utah.gov/rsgis2/search/Display.asp?FlNm=colaaura

Complete Birds of North America, ed. Jonathan Alderfer, National Geographic, 2006, https://www.amazon.com/National-Geographic-Complete-Birds-America/dp/0792241754/ref=pd_bbs_sr_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1213078747&sr=8-1

Moore, William S. Wiebe, Karen L. Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: , March 4, 2020 https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/norfli/cur/introduction

Andelt, W.F., Hopper, S.N., and Cerato, M (8/14),(Revised by M. Reynolds), Preventing Woodpecker Damage – 6.516 , Colorado State University Extension, https://extension.colostate.edu/topic-areas/natural-resources/preventing-woodpecker-damage-6-516/

Woodpeckers, Texas Parks & Wildlife, State of Texas, https://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/publications/nonpwdpubs/introducing_birds/woodpeckers/

Link, Russell, Urban Wildlife Biologist, Living with Wildlife – Northern Flickers, Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, 2005, https://wdfw.wa.gov/publications/00623

One of the World’s Largest Shrimp Buffets by Holly Strand

One of the World’s Largest Shrimp Buffets

from the Great Salt Lake

Courtesy USGS

One of the most unique and important habitats in Utah is the Great Salt Lake. It’s the largest U.S. lake west of the Mississippi River and it’s the 4th largest terminal lake (meaning it has no outlet) in the world. The waters of the Great Salt Lake are typically 3 to 5 times saltier than the ocean . For that reason, you won’t find any fish; in fact, the largest aquatic animals are brine shrimp which are little crustaceans that are found worldwide in saline lakes and seas. You may know the brine shrimp as “sea monkeys” as they are called when packaged and sold as novelty gifts.

Brine shrimp like their water to be between 2 and 25 percent salt. The Great Salt Lake species is especially well adapted to cold . If the temperature is moderate and there is plenty of algae to eat, the females will produce more live young. As temperatures lower, food supply decreases, or other stress factors appear, females will switch to producing cysts which are tiny hard-shelled egg-like spheres. Cysts are metabolically inactive, and can survive without food, without oxygen, even at below freezing temperatures. During winter, the adult brine shrimp typically die from lack of food or low temperature, but the cysts are able to survive the winter and form a large population base for the next generation of brine shrimp.

Brine shrimp practically fill the Great Salt Lake. At times, they become so numerous that you can see them as large reddish-brown streaks on the surface of the lake. Because birds like to eat them, the Great Salt Lake supports one of the largest migratory bird concentrations in Western North America. Birds like the Eared Grebe and Wilson’s Phalarope reach their largest concentrations anywhere as they load up at one of the world’s largest shrimp buffets. In all, during peak migration you’ll find 2 to 5 million birds using the Great Salt Lake to obtain the nourishment required for their long and strenuous trip. It’s fascinating that these tiny prehistoric crustaceans play such an important role in sustaining the large number and wide variety of birds that travel through or live in our State.

Credits:

Audio: Sound for this recording was generously provided by the Western Soundscape Archive at the University of Utah J. Willard Marriott Library. https://westernsoundscape.org/

Photo: Courtesy USGS, https://ut.water.usgs.gov/greatsaltlake/shrimp/

Text: Stokes Nature Center: Anna Paul, Holly Strand logannature.org

Sources & Additional Reading

USGS, Utah Water Science Center, Brine Shrimp and Ecology of Great Salt Lake. (Courtesy Internet Archive Wayback Machine, Apr 15, 2008) https://wildaboututah.org/wp-content/uploads/080415-Wayback-USGS-Brine-Shrimp-and-Ecology-of-Great-Salt-Lake.pdf Formerly: https://ut.water.usgs.gov/greatsaltlake/shrimp/

US Fish and Wildlife Service, Bear River Migratory Refuge. https://www.fws.gov/bearriver/

Westminster College GSL Project –

https://people.westminstercollege.edu/faculty/tharrison/gslfood/studentpages/brine.html

Great Salt Lake, Utah, USGS, https://pubs.usgs.gov/wri/wri994189/PDF/WRI99-4189.pdf

Great Salt Lake Ecosystem Program, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, State of Utah, https://wildlife.utah.gov/gsl/

Larese-Casanova, Mark, The Brine Shrimp of Great Salt Lake, Wild About Utah, Jan 6, 2011, https://wildaboututah.org/the-brine-shrimp-of-great-salt-lake/

Brine Shrimp, Genetic Science Learning Center, University of Utah, https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/gsl/foodweb/brine_shrimp/

Salt Lake Brine Shrimp, https://saltlakebrineshrimp.com/harvest/

Brine shrimp officially named Utah’s state crustacean, March 20, 2023, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Utah Department of Natural Resources, State of Utah, https://wildlife.utah.gov/news/utah-wildlife-news/1608-brine-shrimp-officially-named-state-crustacean.html