made by a tephritid fly Aciurina trixa

Image courtesy and Copyright Jim Cane

Fly identification courtesy Gary Dodson

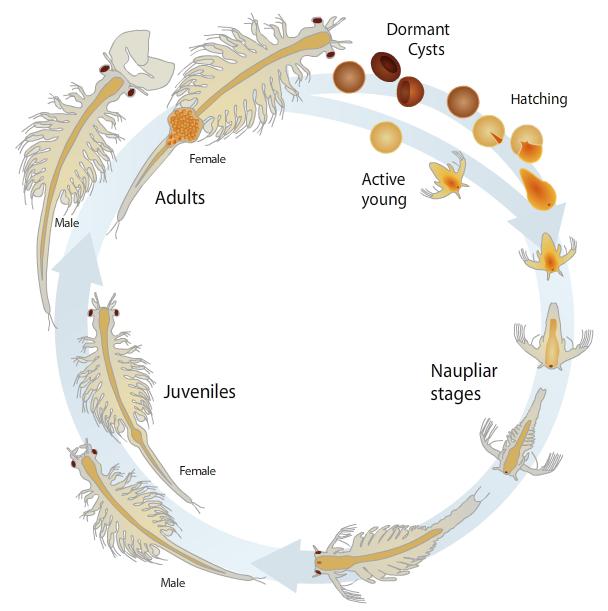

Does Utah have more Gauls than Caesar conquered? Certainly not Gaulish peoples of the ancient Roman Empire, but yes, galls of the vegetal kind we have aplenty. Galls are small protuberant growths on plants that are induced hormonally by insects, nematodes, and microbes. For its resident juvenile insect, the gall is a sort of edible fortress.

Some plant galls made by insects persist into winter, when they are more apparent to the naturalist’s eye. Looking at just rabbitbrush, you can find a menagerie of galls shaped like peas, pineapples and spindles that were formed from leaves, buds and stems. No growing tissue is immune to galling. The morphology of a gall is often diagnostic for the species of juvenile insect within. Gall-making insects are all tiny and include gall midges and tephritid flies, cynipid gall wasps, various nondescript moths, and any number of aphids and their kin.

One aphid causes the unsightly brown galls on branch tips of blue spruce, a bane to homeowners. Another aphid forms the pea-shaped galls that swell leaf petioles of aspens and cottonwoods. On sagebrush can be found a leaf gall whose soft surface surpasses that of a puppy’s ear. Oaks and willows host a remarkable diversity of galls. One oak gall was formerly used for tanning leather and making inks because it is rich in tannic acids. The Hessian fly is of grave agricultural importance today because its stem galls weaken wheat stems, causing them to lodge over.

galls on Rabbitbrush

Image courtesy and Copyright Jim Cane

Fly identification courtesy Gary Dodson

But these are exceptions; most galls are of little or no ecological or economic importance. For that reason, most galling insects remain understudied by all but a handful of passionate specialists. Finding plant galls is easy, and once you begin to notice them, you will find it hard to stop. There is no guide to Utah’s plant galls, but we list several starting references for you on our web site.

This is Linda Kervin for Bridgerland Audubon Society.

Credits:

Photos: Courtesy and Copyright Jim Cane

Text: Jim Cane, Bridgerland Audubon Society

Additional Reading:

Sagebrush Gall made by the fly Rhopalomyia pomum, https://bugguide.net/node/view/200946

Robert P. Wawrzynski, Jeffrey D. Hahn, and Mark E. Ascerno, Insect and Mite Galls, WW-01009 2005,

University of Minnesota Extension, https://www.extension.umn.edu/distribution/horticulture/dg1009.html

Image Courtesy and Copyright Jim Cane

Field Guide to Plant Galls of California and Other Western States by Ron Russo

ISBN: 978-0-520-24886-1 https://www.amazon.com/California-Western-States-Natural-History/dp/0520248864

Gall, Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gall (Accessed Dec 2010)

Gagné R (1989) The plant-feeding gall midges of North America. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

https://www.amazon.com/Plant-Feeding-Midges-North-America-Comstock/dp/0801419182