The Prehistoric Museum,

USU Eastern Campus, Price, UT

Courtesy Mary Heers, Photographer

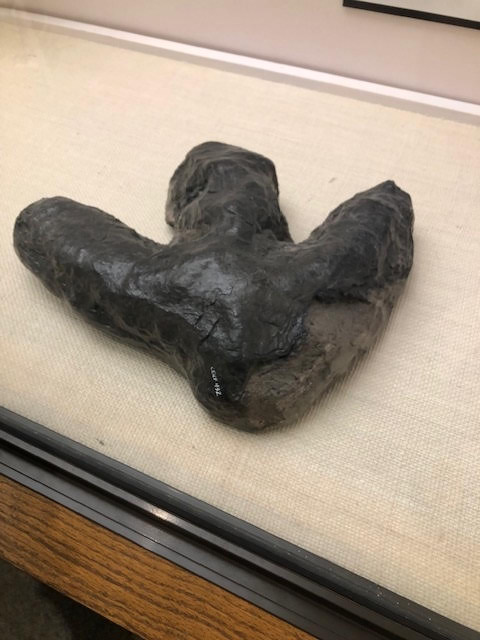

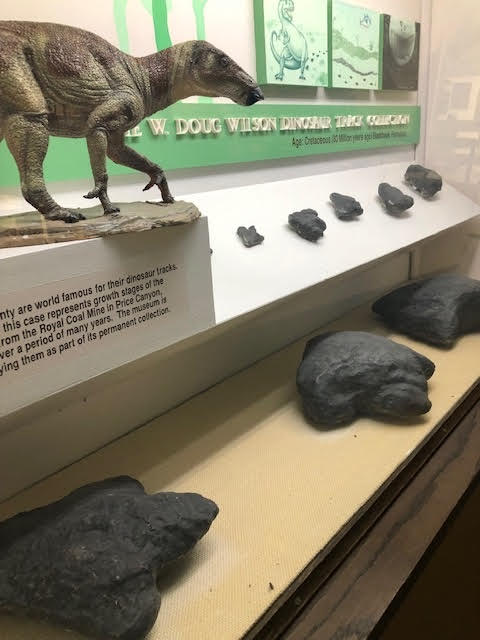

Dinosaur Footprint Display

Dinosaur Footprint Display

The Prehistoric Museum,

USU Eastern Campus, Price, UT

Courtesy Mary Heers, Photographer

When I saw my first giant dinosaur footprint a the Natural History Museum of Utah, I said it was terrific.

“Dime a dozen, “ said my father-in-law, who was standing next to me. “The ceiling of the coal mine is littered with them.”

My ears perked right up. “Really,?” I said. “Maybe I could get one?”

As a young mining engineer right out of college, my father in law had been hired to run the Sunnyside coal mine about 25 miles outside of Price. He went on to explain that it was impossible to take a footprint out of the mine ceiling with risking bringing the whole roof down on your head. I had to agree it sounded difficult, but that didn’t stop me from sighing and saying, “I sure would like a dinosaur footprint for Christmas. “

In the end, he compromised by arranging a trip into the mine to see the footprints.

So, on a day no one was working in the mine, we climbed into the low riding miner’s car that carried us deep, deep into the heart of the mountain. When we got to the face we stopped and got out. In the dim light of our headlamps I could see we were in a huge cavernous room with massive pillars of coal, seven feet high and almost as wide, holding up the roof. And then I looked up and saw them – three toed footprints pressed down into the ancient mud that had turned into coal millions of years ago. Whole families of dinosaurs had strolled through this prehistoric swamp, leaving big prints, as long as two feet, and small ones, as small as six inches.

I found out later that the preservation of these footprints was a happy accident of sand filling up the prints soon after they were made. Millions of years later, when the decaying swamp plants were compressed into coal, the sand (itself pressed into sandstone,) held the shape of the foot.

A similar lucky mix of sand, water and pressure was needed to preserve dinosaur bones. Not all bones become fossils. So you can imagine the excitement in the scientific community when a fossil bed containing more than 12,000 dinosaur bones were discovered 30 miles south of Price. There were enough bones to qualify as a crime scene. To this day, my favorite spot in the Natural History Museum of Utah is the corner where 4 paleontologists on 4 TV screens square off with their earnest explanations for this massive bone pile-up.

One says it was a watering hole that dried up so the dinosaurs died.

“No,” says the second. There was too much water. The site became so muddy that the dinosaurs got stuck in the mud.

The third offers up the idea that it could have been poison or a lethal germ that got in the water.

“Oh, no,” says the fourth. The dinosaurs died somewhere else, and floodwaters floated them here.

It’s a mystery still waiting to be solved, and that’s what makes studying Utah’s past so interesting.

This is Mary Heers, and I’m Wild About Utah.

Credits:

Photos: Courtesy Mary Heers,

Featured Audio: Courtesy & Copyright © Friend Weller, Utah Public Radio upr.org

Text: Mary Heers, https://cca.usu.edu/files/awards/art-and-mary-heers-citation.pdf

Additional Reading: Lyle Bingham, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading

Wild About Utah, Mary Heers’ Wild About Utah Postings

Sunnyside Coal Mines, UtahRails.net, Last Updated March 8, 2019, https://utahrails.net/utahcoal/utahcoal-sunnyside.php

Prehistoric Museum, USU Eastern Campus, Price, UT, https://eastern.usu.edu/prehistoric-museum/

Natural History Museum of Utah, Rio Tinto Center, University of Utah, https://nhmu.utah.edu/