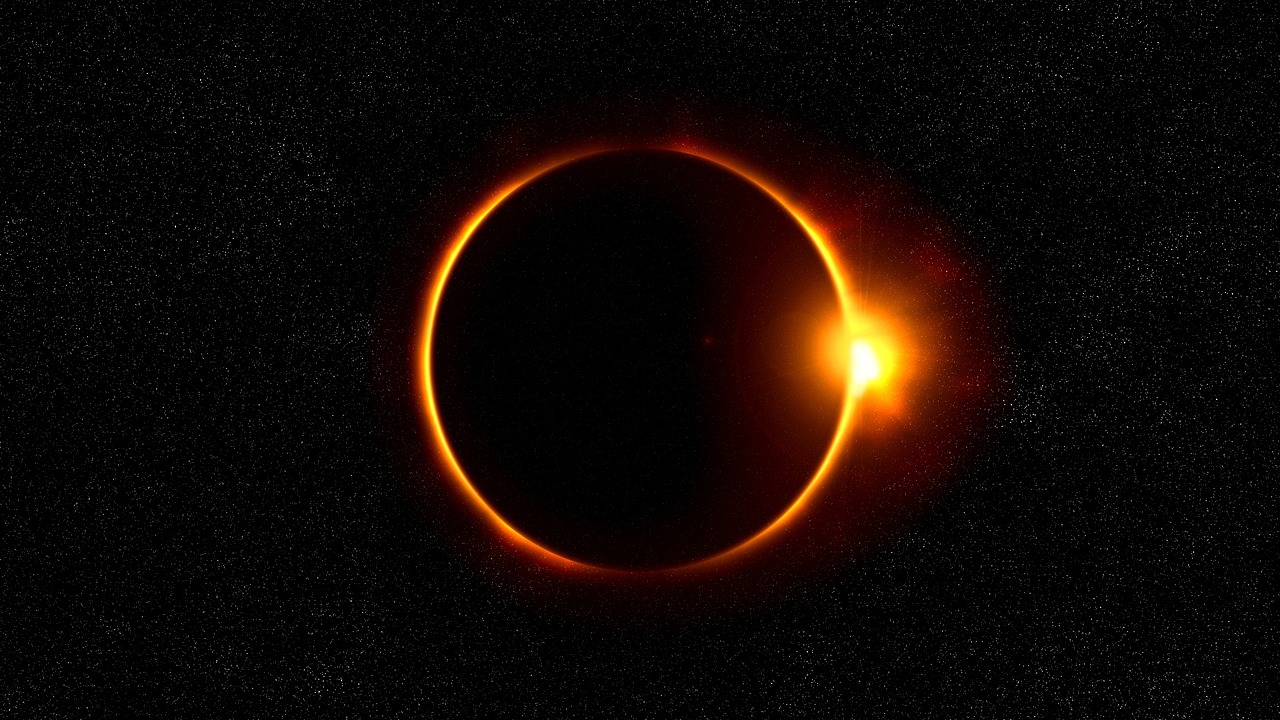

Solar Eclipse-The Diamond Ring

Courtesy Pixabay

Buddy Nath, Contributor

I believe we’re all aware that the amount of light has major influence on wildlife activity, as it does our own, triggering everything from breeding and feeding activity and various behaviors in general. Thus the very short period of light variation during a solar eclipse has piqued my interest.

When a total eclipse crossed over New England in 1932, researchers put out a call for people to share their wildlife observations probably the first study to intentionally track animals during an eclipse—people reported owls hooting, pigeons returning to roost, and a general pattern of bird behavior that suggested “fear, bewilderment, Purple Martins pausing their foraging and nighthawks flying in the afternoon. Whooping cranes dance shortly after the eclipse, and flamingos congregate. For many birds, it’s probably a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

A citizen scientist watched a yellow okra flower close during totality, just as it would at night—a favorite observation of Alison Young, co-director of the Center for Biodiversity and Community Science at the California Academy of Sciences and lead author of a paper describing the findings. The flower’s response was unexpected, she says in an email, since totality wasn’t very long.

During the 2017 eclipse, more than 600 observers submitted their findings to iNaturalist” a community science effort where observations described an absence of wildlife during the eclipse’s peak: busy bird feeders clearing out, insects going quiet, flowers closing up. Other community scientists noted bees quieting their buzzing in flower patches, zoo animals going through their nighttime routines, and Chimney Swifts swooping and twittering like it was dusk

The Eclipse Soundscapes project is also looking for observers to record and share “field notes” of the changes they see, hear, and feel during the eclipse, whether they’re in the total path or not. By going beyond the visuals, the Soundscapes team hopes to make the big day more accessible for blind or low-vision people who are often left out of astronomy, and to help everyone have a deeper experience of the rare event. “What we’re trying to do is have people be very mindful during the eclipse, and actually use all of their senses to determine what changes. Their resulting study found that as the moon started to cover up the sun, there was a drop in biological activity in the air—suggesting that day-flying birds and insects were coming down to rest.

Countrywide, people noticed swallows and swifts flocking as darkness fell. Frogs and crickets, common elements of an evening soundscape, started to call, while diurnal cicadas stopped making noise. Ants appeared to slow down or stop moving, and even domestic chickens responded—hens gathered together and got quiet, while roosters crowed.

Even in the partial zone, you can still pay attention to how nature responds—and contribute to science. Sending in your observations through a platform like iNaturalist or eBird can help provide valuable data for future research,

Jack Greene for Bridgerland Audubon, and I’m wild about Utah!

Credits:

Images: Eclipse Pixabay, AlpineDon, Contributor, https://pixabay.com/photos/snow-canyon-state-park-utah-1066145/

Featured Audio: Courtesy & © Anderson, Howe and Wakeman,

Courtesy & Copyright © Kevin Colver, https://wildstore.wildsanctuary.com/collections/special-collections/kevin-colver

Also includes audio Courtesy & © J. Chase & K.W. Baldwin

Text: Jack Greene, Bridgerland Audubon, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading: Lyle Bingham and Jack Greene, Author, Bridgerland Audubon, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading:

Jack Greene’s Postings on Wild About Utah, https://wildaboututah.org/author/jack/

iNaturalist

Ohio Wildlife Observations: Solar Eclipse 2024 https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/ohio-wildlife-observations-solar-eclipse-2024

The Eclipse Soundscapes project

2024 Total Solar Eclipse: Through the Eyes of NASA

EarthSky: How Will Animals React During the Eclipse?

Watch Videos from EarthSky Countdown to Eclipse 2024: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLcwd1eS7Gpr6QrjJU7aH5K7qBCIb39ECP

Day

Whitt, Kelly Kizer, When is the next total solar eclipse? April 9, 2024, https://earthsky.org/astronomy-essentials/when-is-the-next-total-solar-eclipse-dates-location/