If you’ve ever hiked or driven up Green Canyon near the City of North Logan, you’ve probably noticed the dried-up streambed. It wasn’t always dry, however. In fact, if you turn back the pages of history you’ll find water, and the story of why the stream no longer flows.

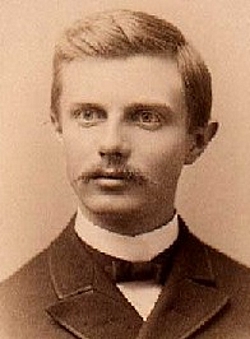

In the 1920s several families living in North Logan contracted meningitis from drinking contaminated canal water. The townspeople had tried drilling wells, but each time the water emerged from the ground warm and metallic. Farres Nyman, an early resident of North Logan recorded that during winter her father would chop holes in the frozen Logan-Hyde-Park Canal to retrieve drinking water. Her mother would then “take a little strainer and strain out the wrigglers and boil our drinking water.”1 One of the people infected was Utah State Agricultural College engineering professor Orson W. Israelsen. His bout with the illness left him completely deaf.2 The meningitis outbreak motivated the community, and especially Israelsen, to find a clean source of water for North Logan.

With the help of his students at the Agricultural College, Israelsen explored Green Canyon. Sometime in 1928, the group located a spring five miles up in a narrow adjacent canyon (now called Water Canyon). From 1928–1934 Israelsen sent students, often on snowshoes, to gather flow data from the spring. He determined that the spring’s average discharge of around 88 gallons per minute was sufficient to meet the needs of the community.3

The spring was already spoken for by a local power company and the Little Flower Mine, who owned rights to the water jointly, but in 1928, the power company decided not to re-file. And so on October 1st of the same year (when the water rights came up for renewal) North Logan resident Robert Burns Crookston camped out near the state offices in Salt Lake City and claimed the water for North Logan before a representative for the Little Flower Mine had a chance to re-file.4

With the water now theirs, residents of North Logan decided to incorporate as a town. In 1934 town leaders laid out their plan to construct a waterline to bring the spring water in Green Canyon to their homes in the valley. Orson W. Israelsen was put in charge of the project. He estimated it would cost $24,000$35,000 to build the waterline. To defray costs, the city sought help from the Federal Government. Through the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Uncle Sam contributed $32,850 while North Logan City raised another $28,800. Surveying took place during November 1934 and men began digging trenches in Green Canyon during the winter of 1935.5 Israelsen described the work:

There was no digging equipment at that time, a pick and shovel and crowbar were used. When they came to a level, a plow or root digger was used, which was drawn by a team of horses. This loosened the soil, which the men lifted out of the trenches with a shovel… They were interested in their town welfare and did the job on the 5 miles of pipe in the canyon and 8 miles in the valley. What a joy it was to turn a tap and get a clear cold drink of pure water6.

Despite the difficult work, the men made good time. By June 1935 water was flowing from the spring in Green Canyon to residents in North Logan.

Not much has changed since 1935. The spring continues to send clean water to homes in North Logan, just as Israelsen and the WPA workers hoped it would. Until 1984 North Logan City used the original pipe. However, severe flooding during the winter of 1983–84 washed out sections of the old pipe, requiring installation of new pipe.7 The new pipe is even more efficient, capturing all the spring water that once tumbled down Green Canyon spreading life. These days the streambed is full of dusty hikers and mountain bikers instead of water. And, the cottonwoods and willows that made Green Canyon so green have dried up, reminding us of our history and the cost of clean drinking water.

For Wild About Utah, I’m Brad Hansen

Footnotes:

-

- Jesse L. Embry, North Logan Town: 1934-1970. (North Logan, Utah: North Logan City, 2000), 25.

-

- “Biographical Sketch,” Orson Winso Israelsen Papers, (1894-1966), (Available at Special Collections and Archives, Utah State University), accessed April 25, 2012, https://library.usu.edu/specol/manuscript/collms31.html

-

- Lydia Thurston Nyman and Venetta King Gilden, Miscellaneous Papers on the History of North Logan, Utah. (Published by Authors: 1998), 60.

-

- Don Younker Oral History, interviewed by Jessie Embry, 1998, 6.

-

- Thurston and Nyman, 61.

-

- Ibid, 61.

-

- Al Moser Oral History, Interviewed by Daniel Franklin and Sean Harvey, February, 2012.

Credits:

Photo: Courtesy Utah State University Special Collections and Archives

Text: Brad Hansen

Sources & Additional Reading