https://www.azwater.gov/AzDWR/StatewidePlanning/CRM/images/map_main_large.jpg [Feb 27, 2014]

Courtesy AZwater.gov

Hi, this is Mark Larese-Casanova from the Utah Master Naturalist Program at Utah State University Extension.

The Colorado River Compact, written into law almost a century ago, helped ensure our survival in Utah today. We all know that Utah is a dry state. In fact, Utah is the second driest state in the country, with only Nevada being drier. Our average annual precipitation varies widely, from as low as a few inches a year near St. George, to as high as 60 inches in the mountains. Since most of our water comes from mountain snow, we rely on rivers and streams to deliver it to us.

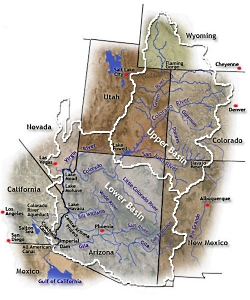

The Colorado and Green Rivers, the largest in Utah, carry water from the Rocky, Wasatch, and Uinta Mountain ranges throughout Utah and the Intermountain West. The Colorado River Basin, the area of land from which the Colorado River and its tributaries drain water, covers the eastern half of Utah, along with the western half of Colorado, almost all of Arizona, and small parts of Wyoming, New Mexico, Nevada, and California. Each of these states has a dry climate, and water from the Colorado has always been in high demand.

In the heavily populated eastern United States, the right to use water often adheres to Riparian Doctrine in which water is shared by all those who live along the body of water. However, the western US was settled at different times, and populations are more sparse. So, water rights generally follow the doctrine of Prior Appropriation. That is, the water is set aside for whoever is able to use it first. The only problem is that California was developed earlier than the other states in the basin, and therefore, as the US Supreme Court ruled in 1922, was legally entitled to more than their fair share of the water! In this case, western water law simply didn’t work. So, all 7 states in the Colorado River Basin sat down together with the US Government and negotiated the Colorado River Compact to ensure that Utah and the other Upper Basin states were entitled to as much water each year as California and the other Lower Basin states that were growing at a faster rate.

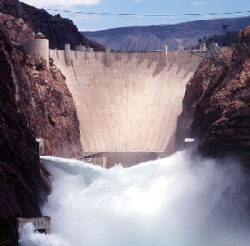

So there you have it- one key piece of legislation helping to save civilization in Utah. Except, well, the amounts of water each state is entitled to was based on an abnormally high year of water flow… and, so, there often isn’t enough water to go around… and Mexico doesn’t seem to get much water at all. OK, so the Colorado River Compact isn’t perfect, but it’s important. To ensure that we all truly have enough water, it will take compromise, conservation, and a whole lot of common sense.

For Wild About Utah, I’m Mark Larese-Casanova.

Credits:

Images: Courtesy AZwater.gov

Text: Mark Larese-Casanova

Additional Reading:

Gelt, J. Sharing Colorado River Water: History, Public Policy and the Colorado River Compact. Water Resources Research Center. https://wrrc.arizona.edu/publications/arroyo-newsletter/sharing-colorado-river-water-history-public-policy-and-colorado-river

US Bureau of Reclamation. The Colorado River Compact. https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/pao/pdfiles/crcompct.pdf

US Bureau of Reclamation. The Law of the River. https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/pao/lawofrvr.html

Law of the River, Colorado River Management, State of Arizona, https://new.azwater.gov/crm/law-river

Water Education Foundation. 1922-2007: 85 Years of the Colorado River Compact. https://www.watereducation.org/western-water-excerpt/1922-2007-85-years-colorado-river-compact

James, Ian, Scientists have long warned of a Colorado River crisis, The Los Angeles Times, July 15, 2022, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-07-15/scientists-have-long-warned-of-a-colorado-river-crisis

Air Pressure at the Surface, 1 Dec 2011

Air Pressure at the Surface, 1 Dec 2011